For decades the magazine the New Yorker has been famous for its wonderful cartoons, such as the classic cartoons of Charles Addams. But the New Yorker has also long been famous for long essays. A recent essay in the magazine was a long article entitled "A Journey to the Center of Our Cells." It is a good thing that a major magazine should attempt to educate us about the fundamentals of cells, a deep and profound topic that can be a springboard to more intelligent ideas in biology. Unfortunately, what the article gives us is a kind of shrink-speaking complexity-concealment affair like we so often read, an essay that repeatedly gives us wrong ideas and incorrect impressions.

Two huge errors occur very early in the essay. The first is in the subtitle, which makes the untrue claim that scientists are learning to build their own cells. No progress has been made in making self-reproducing cells from scratch or from protein components. Then we read, "We accept that each of us was once a single cell, and that packed inside it was the means to build a whole body and maintain it throughout its life." It is very false indeed to state that a fertilized ovum or human egg contains "the means to build a whole body and maintain it throughout its life." Such a fertilized ovum or egg contains only DNA with low-level chemical information, such as partial instructions for making protein molecules. DNA does not contain any instructions for building bodies or limbs or organ systems or skeletons or cells. DNA does not even contain instructions for making the organelles that are the components of cells. So how does a full-grown body with its many levels of hierarchical organization (and about 200 types of cells, most as organized as a factory) arise from a mere speck-sized cell containing no instructions for making such a wonder of functional complexity and vast hierarchical organization? That is a mystery a thousand miles over the heads of today's scientists.

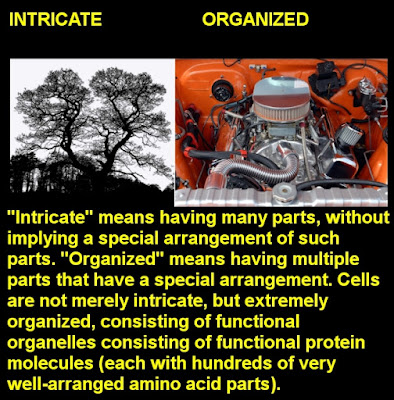

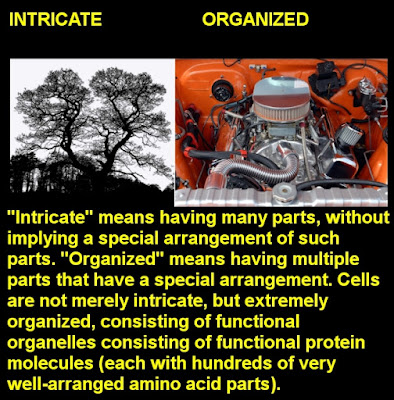

Just as automobiles are wonders of organization (marvels involving very many parts arranged in the right way to achieve a functional end), cells are wonders of vast organization (marvels involving very many parts arranged in the right way to achieve a functional end). But you would never know that from reading the New Yorker article. We do not find the words "organized" or "organization" in the article, except for a most dubious reference to "self-organization." The article refers to cells as "incredibly intricate," but that is not an adequate term to describe cells. "Intricate" means "very complicated or detailed." Countless non-functional things are intricate. Cells are something much more than intricate: they are incredibly organized, internally dynamic and functionally complex.

The article mainly speaks of "the cell," as if there was one type of cell. Nowhere are we told about all the different types of cells, except when the article mentions four types, by saying, "The human body contains brain cells and

fingernail cells, blood cells and muscle cells, and dozens of species

of single-celled bacteria." Human beings actually have about 200 different types of cells, with characteristics as diverse as the diverse characteristics of the creatures in the Bronx Zoo. Just as each of the roughly 20,000 types of protein molecules in the human body is its own separate very complex invention, each of the roughly 200 types of cells in the human body is its own separate very complex invention. Why the failure to tell us about such a reality?

The article then tells us, "Several groups of 'synthetic

biologists' are now close to assembling living cells from nonliving

parts." This claim is a huge falsehood. A living cell would be a cell capable of self-reproduction. Scientists have no understanding of what causes cells to reproduce. So scientists are nowhere close to assembling living cells from nonliving parts. On a web page entitled "The Mystery of Cell Division," a scientist confesses that scientists don't understand how cells -- with a complexity of "airplanes" -- could self-reproduce. We read this:

"Scientists have been trying to understand how cells are built since the 1800s. This does not surprise us and, as scientists ourselves, we have always been puzzled at how cells, such complex structures, are able to reproduce over and over again. Even more astonishing is that, despite the frequency of cell division, mistakes are relatively rare and almost always corrected. According to Professor David Morgan from University of California, the complexity that we observe in cells can be compared to that of airplanes."

An M. Pitkanen (who has a PhD in theoretical physics) has written the following about cell division:

"Replication is one of the deepest mysteries of biology. It is really something totally counterintuitive if cell is seen as a sack of water plus some chemicals. We have a lot [of] facts about what happens in the replication at DNA level but how this miracle happens is a mystery. At cell level the situation gets even more complex."

A university press release discusses scientific ignorance about the basis question of cell division. It states the following:

"When a rapidly-growing cell divides into two smaller cells, what triggers the split? Is it the size the growing cell eventually reaches? Or is the real trigger the time period over which the cell keeps growing ever larger?...'How cells control their size and maintain stable size distributions is one of the most fundamental, unsolved problems in biology,' said Suckjoon Jun, an assistant professor of physics and molecular biology at UC San Diego...'Even for the bacterium E. coli, arguably the most extensively studied organism to date, no one has been able to answer this question.' ”

Later the New Yorker article makes the big mistake of equating a cell with its genes. It says, "Decipher the labelled genes and you’d

approach a comprehensive understanding of cellular life." To the contrary, neither DNA nor its genes specify how to make a cell or any of its component organelles; and neither DNA nor its genes specify the incredibly complex biochemistry of cells. DNA and genes influence cellular behavior, but do not specify it. Later the New Yorker article makes the unwarranted claim that protein molecules "self-assemble into biological machines." We do not know how incredibly complex organelles, cells, organs, organ systems and bodies arise from the low-level components that are protein molecules, and we should not be pretending to understand such a mystery (a thousand miles over our head) by using the empty term "self-assemble."

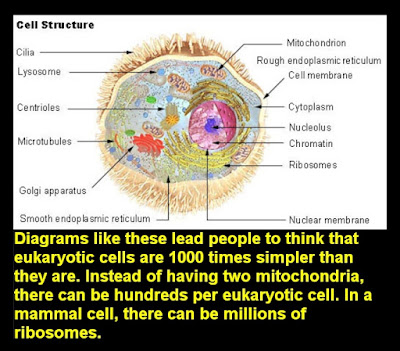

The New Yorker article fails to explain the basic structural reality that a human cell contains thousands of functional components called organelles. In this sense, a human cell is like some car engine or aircraft carrier engine containing thousands of functional parts arranged in just the right way. Such a reality will be suprising to those who remember the thousand-fold oversimplified and extremely misleading cell diagrams in biology textbooks, which falsely depict cells as having only a few dozen organelles.

Instead of describing this reality of vastly organized cell structure, the New Yorker article rather tries to depict a cell as if it was a mere bag or heap of proteins. It states this:

"If a cell were blown up to the size of

a high-school gym, you wouldn’t be able to see across it. It would

be filled with tens of thousands of proteins, most about the size of

a basketball. Other biomolecules no bigger than your hand, and water

molecules the size of your thumb, would fill the spaces between. (To

scale, your whole body would be about the size of a ribosome.) The

mixture would have the consistency of hair gel."

This is as misleading as describing the US Capitol Building as being kind of a big heap of carbon, oxygen and iron molecules. Hair gell is disorganized. Cells are enormously organized.

There is a world of difference between the simplest type of cells (called prokaryotic cells) and the type of cells found in the human body (called eukaryotic cells). It has been said that the difference between prokaryotic cells and eukaryotic cells is like the difference between some one-room shack and a billionaire's mansion. What visual do we see at the top of the "A Journey to the Center of Our Cells" article in the New Yorker, an article with a title suggesting a discussion of human cells? Not a visual of a eukaryotic cell, but a visual of a prokaryotic cell. This is consistent with the whole thrust of the article, which seemingly is to conceal from us the complexity and organization of our cells, and to make us think our cells are vastly simpler than they are.

Later the New Yorker article approvingly quotes some physicist saying, "This area of understanding how

colloidal-scale physics is regulating and orchestrating cell

function—this is the frontier." The statement is very laughable and extremely misleading. Physics does not orchestrate cell function. Cells involve operations as complex as the construction of a skyscraper, and cannot be explained by simple rules of physics. Saying that cell function is orchestrated by physics is like saying the construction of a skyscraper is orchestrated by the law of gravity.

In the last paragraph, the New Yorker article tries to create the impression that "synthetic life" has been created. It states this:

"Before I left town, Glass gave me a

memento. It was a strange-looking cube, a sort of clear plastic

paperweight with a pink square suspended inside. Glass explained that

the square was a plate of agar on which colonies of the minimal cell

had been grown. The colonies were encased in a few inches of resin. It’s on my desk now. Holding it up to

the light, I can make out perhaps a dozen pinpricks. I wonder what

these colonies—some of the first examples of synthetic life—will

come to be seen as initiating."

The impression here is enormously misleading. The work in question by Glass involves stripping genes out of existing living cells, to try and find how many genes can be taken out without destroying a cell's ability to reproduce (rather like experimenting with how many parts can be removed from a mouse without killing the mouse). That isn't anything like creating synthetic life, which would be creating a living reproducing thing from some non-living inert substances. No one has produced any such thing as synthetic life, nor is anyone anywhere close to doing such a thing, which we should not expect to occur in this century.

Given its very great internal complexity and very high state of functional organization, the reproduction of a cell is a marvel that can be compared to a working automobile splitting up to become two full-sized automobiles. The author of the New Yorker article seems to have little understanding of how hard it would be to ever explain such a marvel or to cause it by tinkering with lifeless matter. The author fails to even mention cell reproduction, merely referring to cell division, something sounding much less impressive. Inanimate lifeless things like books can be easily divided into two, but they can't reproduce. At one point the article laughably suggests that scientists may be able to get living cells from scratch after they have spent some more time tinkering with "different ingredients" or by fiddling with part arrangements. This is like suggesting that if you tinker a little more with a car engine, you can get the car to split into two working cars.

By referring to "different ingredients" in a cell, the article is using a common technique of complexity-concealing writers trying to make something sound vastly less organized than it is. Although sometimes defined as a part or a component, the term "ingredient" is a word with a strong connotation implying something within an unordered mixture such as a pot of soup. The wikipedia.org article on "ingredient" begins by saying, "An ingredient is a substance that forms part of a mixture (in a general sense)." Cells are very complex functional arrangements of matter that are no more mixtures than the engine of a car is a mixture.

Instead of giving us some incorrect impression that scientists such as John I. Glass are creating synthetic life, our New Yorker author should have properly analyzed and reported on papers co-authored by Glass such as the paper "Fundamental behaviors emerge from simulations of a living minimal cell." That paper describes "a genetically minimal bacterial cell, consisting of only ... 493 genes on a single 543-kbp circular chromosome with 452 genes coding for proteins (), some of which are subunits of multi-domain complexes." Each of those genes is a complex invention with hundreds of fine-tuned parts that almost all have to be just right. The total number of amino acids that have to be arranged just right in the proteins partially specified by these genes is roughly 150,000. Far from supporting any "life is simple, we can make it from scratch" narrative, such a paper supports the idea that even the simplest self-reproducing cell has a degree of organization and functional complexity greater than the organization and functional complexity of an 80-page technical manual. And even all that information does not give you a self-reproducing cell; it's only a prerequisite for such a cell.

The extremely misleading give-you-the-wrong-ideas article that is "A Journey to the Center of Our Cells" reminds me of another extremely misleading give-you-the-wrong-ideas article recently published in the same magazine: its "The Science of Mind Reading" article that is debunked here. The first article attempts to advance the groundless idea that scientists are making some progress in creating synthetic life from lifeless materials. The second article attempts to advance the groundless idea that scientists are making some progress in reading thoughts by scanning brains.

No comments:

Post a Comment