“This

is why dark matter and dark energy are good scientific explanations.

They are simple and yet explain a lot of data.”

But

I will argue the following:

- Hossenfelder was not speaking in a scientific manner when she stated “dark energy and dark matter are entirely normal.”

- Hossenfelder was not speaking in a scientific manner when she stated dark energy and dark matter are “perfectly scientific hypotheses.”

- Hossenfelder was not speaking in a scientific manner when she stated dark energy and dark matter “are simple.”

First,

let us delve into the question of what it is to be scientific. The

definition I get when I do a Google search for "scientific" is “based on or

characterized by the methods and principles of science.” Upon

hearing such a definition, the idea that dark matter or dark energy

could be scientific sounds very strange and far-fetched. How could

some undiscovered postulated particles be “based on or

characterized by the methods and principles of science”?

The

term “scientific” is not really something we should be using

about physical entities, whether observed or unobserved. It makes no

particular sense to say something such as “the moon is scientific”

or "the ocean is scientific" or “dark energy is scientific.” The term “scientific” is one

that should be used mainly when referring to speech, writing, and behavior.

What

are some of the things that make writing, speech or behavior

“scientific”? The two biggest hallmarks I can think of are the

following:

- Scientific behavior is conduct that involves very careful and precise observations and very careful and precise recording of such observations.

- Scientific speech uses language that is precise, accurate and unambiguous.

It

is easy to give examples of speech that is scientific and speech that

is unscientific. If I say, “The instant I saw him I knew he'd

taken more than he could handle, because he had this kind of 'hit by

a tidal wave' look that showed he was in for a world of trouble,”

that is not at all scientific language. It's not scientific mainly because

it's so ambiguous and imprecise. What is meant by “taken more than

he could handle”? What exactly is meant by a “hit by a tidal

wave” look? What is meant by “in for a world of trouble?” No

one knows. On

the other hand, it would be a scientific language if you said

something like, “On initial examination I observed the patient had

an elevated pulse of 103 beats per minute, a temperature of 102

degrees F, and complaints of weakness and a headache.”

Now,

what about calling some theoretical physical entity “scientific”? It's not scientific to be calling theoretical physical things “scientific.”

Why is that? Because “scientific” is usually not a precise term when used

in any reference that is not a reference to behavior, speech or

conduct.

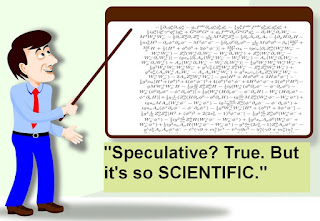

In

fact, when you use the term “scientific” when referring to some

theory of something unobserved, you are using what is called “loaded

language.” Loaded language is language that isn't very precise,

but is heavy with hazy connotations, often emotional or judgmental connotations.

Here

are some “loaded language” terms that are vague, and heavy with

emotional or judgmental connotations, which may be either favorable

connotations or unfavorable connotations:

- un-American

- imperialistic

- propaganda (rather than “messaging”)

- holy

- virtuous

- subversive

- exemplary

- simple (rather than “skimpy”)

- skimpy (rather than “simple”)

- hijack (rather than “use”)

- flourishing (rather than “growing”)

- cancerous (rather than “growing”)

- scientific (rather than “speculative” or “hypothetical”)

- first-rate

- top-notch

- economical (rather than “cheap”)

Notice

that I have included “scientific” on my list of “loaded

language” terms, meaning terms that are vague and heavy with emotional or judgmental connotations. If you are talking about someone's method of

operation, it is fairly clear what is meant by calling such a method

“scientific”: you mean that the method is precise and rich in careful

truthful observations. But what does it mean to call some unverified

speculation “scientific”? It really means nothing precise at all.

But someone may call some speculation "scientific" as a way of evoking a vague

feeling of approval. Calling some speculation “scientific” is

really no more precise or meaningful than calling it “top-notch”

or “first-rate.” Since it's not precise to be calling some

speculation “scientific,” and since being scientific is largely

about being precise, it's

not scientific to be saying things such as “dark matter and dark

energy are scientific.”

What

would be a scientific thing to say about dark matter or dark energy?

It would be a precise statement such as “dark energy is a

mysterious invisible unobserved energy speculatively postulated by cosmologists

to help deal with various observational mysteries they are faced

with.”

But

what about calling dark energy and dark matter “simple” as Hossenfelder did? That is

vague spin-speak that has no precise meaning when used in a

discussion of a scientific theory. When people use the term “simple”

in regard to speculations about nature, what they mainly mean is

“parsimonious,” which means “postulating not very much.”

Neither “parsimonious” nor “simple” is a precise term.

And

there are very good reasons why neither dark matter nor dark energy

should be regarded as simple or parsimonious theories. Dark energy

postulates that there is some unobserved energy that has more

mass-energy than all other observed matter and energy in the

universe. This is the idea that for every observed particle there are

very many unobserved particles. There's nothing parsimonious about

that. Anyone postulating a theory of dark energy will become entangled in the extremely complex "cosmological constant" problem, the problem of why the vacuum does not have an incredibly high energy density because of quantum contributions. This is one of the most complex problems of science. You can't have a dark energy theory without becoming entangled in great complexities.

Dark

matter involves a similar assumption, that for every observed

material particle there are many unobserved invisible particles.

Moreover, dark matter requires you to believe in very specific

assumptions about the arrangement of such dark matter. In order to solve

the observational problems which the idea of dark matter was

contrived to solve, you must believe not just that dark matter

exists, but that dark matter is arranged in very specific ways. We

may compare this to some theory that does not just postulate that

angels exist, but also says that angels live in some very specific

geographical arrangements such as angel kingdoms existing in particular

locations. It is very dubious spin-speak indeed to be calling such

a theory of dark matter “simple.”

As

for Hossenfelder's claims that “dark energy and dark matter are

entirely normal” and that they are “perfectly scientific,”

one might coin the term “double spin-speak” to refer to such

phrases, which are not at all scientific claims, being completely

lacking in the unambiguous precision that characterizes truly scientific claims. Dark matter is supposedly invisible, so how can invisible matter be "entirely normal"? All

in all, Hossenfelder's claims about dark matter and dark energy being

“perfectly scientific” and "simple" and "entirely normal" are no more substantively sound than her strange recent claim about the coronavirus, this lackadaisical thought: “I

feel like there isn’t much we can do right now other than washing

our hands and not coughing other people in the face.” Of course,

there are many other things that we can and should do right now about this extremely severe crisis, including the many things I mentioned in my recent

post on the topic of coronavirus (quoting from my 2013 post on how

to avoid a pandemic), and also the many important and urgent actions

that are being discussed frequently on television these days by

health officials, White House officials, and people like the mayor of New York City and the governor of New York.

The jargon term used by scientists for the theory of dark matter is LCDM, which stands for "lambda cold dark matter." It is interesting that a very recent scientific paper is entitled, "Cosmic Discordance: Planck and luminosity distance data exclude LCDM." The paper is co-authored by Joseph Silk, who was the author of a book on cosmology I read. The authors claim that their analysis "excludes a flat universe" and suggest that the theory of dark matter "needs to be replaced." If they are correct, then we should reject two of the biggest claims cosmologists have made in the past thirty years: that dark matter exists and that the universe has a flat geometry.

A person marketing unproven speculations about invisible never-observed particles may say that his theory is "perfectly scientific." And a US Congressman pitching some pork-barrel legislation may call his bill "truly patriotic." And a theologian advocating some apocalypse dogma may say that his scenario is "genuinely Christian." In each such case of spin-speak, we may say, "an adjective is being used not to say anything precise, but to help sell something by creating a vague positive feeling."

Postscript: A later post by Sabine contains some seriously erroneous teachings, such as the completely misguided claim that "biology can be reduced to chemistry," which is as false as the idea that mental phenomena can be reduced to biology. See here for the utter failure of attempts to do the latter.

A person marketing unproven speculations about invisible never-observed particles may say that his theory is "perfectly scientific." And a US Congressman pitching some pork-barrel legislation may call his bill "truly patriotic." And a theologian advocating some apocalypse dogma may say that his scenario is "genuinely Christian." In each such case of spin-speak, we may say, "an adjective is being used not to say anything precise, but to help sell something by creating a vague positive feeling."

Postscript: A later post by Sabine contains some seriously erroneous teachings, such as the completely misguided claim that "biology can be reduced to chemistry," which is as false as the idea that mental phenomena can be reduced to biology. See here for the utter failure of attempts to do the latter.

Hossenfelder writes: "Dark energy and dark matter are entirely normal, and perfectly scientific hypotheses. They may turn out to be wrong, but that doesn’t mean it’s wrong to consider them in the first place."

ReplyDeleteThis is not the same as saying that dark matter is scientific.

The name of her post is "Are Dark Energy and Dark Matter Scientific?" and the whole purpose of her post is to suggest a "Yes" answer to such a question.

Delete2 X a mega parsec X C, divided by Pi to the power of 21 = 70.98047 K / S / Mpc. This is Hubble's Constant. For this equation, the value of a parsec is the standard 3.26 light years. This comes from 'The Principle of Astrogeometry (Kindle). The reciprocal isa 'fixed' 13.778 billion light years, and as this is also fixed, does not increase with time. This shows the 'big bang', dark matter and dark energy is also false. Theoretical cosmology today is totally on the wrong track, David Hine

ReplyDelete