Last year the New York Post had a misleading editorial by the chief scientist of the SETI Institute, Nathalie Cabrol. It was clumsily entitled "The possibility of life on other planets is more likely than we know," rather than the more concise "life on other planets is more likely than we know," which expresses exactly the same idea in three fewer words. Saluting Carl Sagan, the editorial gives us the same type of baloney and BS on this topic that we often got from Sagan, a scientist who often made very bad misstatements about very important topics.

Early on we have this bit of baloney: "We live in a golden age in astrobiology, the beginning of a fantastic odyssey in which much remains to be written, but where our first steps promise prodigious discoveries." No, actually we don't live in any such "golden age in astrobiology," because astrobiologists have done nothing to show that life exists on other planets; so astrobiology is current a science without a subject matter. And astrobiology (the search for life on other planets) has been going on for more than 60 years, so it certainly is not taking its "first steps." Astrobiology is 65 long years away from "beginning." The first SETI attempt to detect radio signals from extraterrestrials was the Project Ozma launched in 1960. The link here allows you to browse through a table showing all of the main searches for extraterrestrial intelligence, which have been occurring almost steadily since 1960.

Highlights include:

The SERENDIP I project, which from 1979 to 1982 surveyed a large portion of the sky, the portion depicted in Figure 4 of the paper here, a project which a Sky and Telescope article tells us surveyed "many billions of Milky Way stars."

The Southern SERENDIP project lasting 1998 and 2005, which surveyed for some 60,000 hours a large portion of the sky, the portion depicted in Figure 2 of the paper here.

The SETI project discussed here, surveying a significant portion of the sky, the portion depicted in Figure 2 of the paper here.

The all-sky SETI survey discussed here, which operated continuously for more than four years.

The two-year southern sky SETI search discussed here, which observed for 9000 hours and "covered the sky almost two times."

The five-year META SETI project discussed here, which between 1988 and 1993 spent about 80,000 hours of telescope time searching for extraterrestrials.

What would you think of an employee who was assigned some task, and who then said (when asked months later to report his progress) that he "had only just begun" the project, despite working on it for months? You might think that such a guy should not be trusted. But how much worse is it to claim around this year that scientists are "beginning" to search for extraterrestrial life, making "first steps," when such efforts have actually been going on pretty much full blast for 65 years?

We then have from Cabrol a repetition of some of the "we are star stuff" hogwash that Carl Sagan loved to spray. We read this:

"To begin with, the elementary compounds making life as we know it — carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, phosphorus, sulfur — are surprisingly common.

It is no accident that we humans are made of them.

This is the star stuff astronomer Carl Sagan always talked about — not the aliens of Hollywood’s imagination.

This is life — or the building blocks of life — ever-present, but invisible to the human eye."

Sagan would always repeat this "we are all star stuff" mantra, but it was a profoundly misleading claim. The word "stuff" implies a disorganized set of things or disorganized material. For example, if someone said to you, "Let me show you some metal stuff I have in my garage," you would be surprised if the person opened his garage door and pointed at a car. The word "stuff" implies some not-very-organized set of things. For example, someone may say, "I bought some stuff at the food store," referring to various items in a bag that are not any very organized arrangement.

And contrary to the overconfident claims of astronomers such as Sagan, we do not actually know that the heavy elements in our bodies came from stars. Calculations based on the number of supernova explosions in our galaxy (discussed here) suggest that fewer than .0002 of the galaxy should have received elements from supernova explosions. So the claim that the heavier elements in our bodies came from stars is questionable. Scientific accounts of the origin of all elements heavier than iron are shaky, as a recent Quanta Magazine article confesses.

A human being is not "some stuff." Physically a human being is a state of enormous organization, something so vastly organized it is the opposite of what you think of when you hear the phrase "some stuff." And a human is also a mind, something mental, which is not physical stuff.

I think I understand why scientists kept repeating Sagan's extremely misleading claim that "we are all star stuff." One reason is that it was a slogan that serves to dehumanize and depersonalize humans, and to make it sound like a human body is not organized. Scientists are embarrassed by the vast levels of functional organization in the human body. The credibility of all claims of an accidental or unguided origin of the human species are inversely proportional to the amount of functional fine-tuning, information richness, and hierarchical organization in human bodies. The more organized and fine-tuned our bodies, the less credible are claims of an unguided origin of humans. So, clinging to a groundless dogma they cherish (that humans are mere accidents of nature), scientists love to repeat phrases that make human bodies sound like nothing very special. One such phrase is the very misleading phrase "we are all star stuff."

People familiar with the utter inhabitability of the hell-world Venus (twice as hot as a busy pizza oven) may chuckle at these lines by Cabrol talking about a planet revolving around another star:

"This Earth-sized exoplanet, identified using NASA’s TESS satellite system, orbits a cool red dwarf star and shares intriguing similarities with Venus. Signs of habitability are seemingly everywhere."

"Signs of habitability are seemingly everywhere"? What actually happened is that projects such as Kepler and TESS spent years looking for habitable planets, and found only a very small number, probably fewer than 20. Instead of "everywhere," it was more like "1 in a 20,000." Kepler surveyed 500,000 stars, finding fewer than about 20 habitable planets.

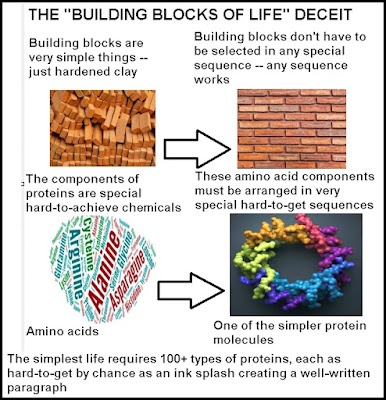

Sounding like someone writing very carelessly, Cabrol says this of elements such as carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, phosphorus and sulfur: "This is life — or the building blocks of life — ever-present, but invisible to the human eye." No, some carbon floating around in space is not life, nor is it a "building block of life." The phrase "building block of life" in reference to atoms or amino acids is profoundly misleading, for reasons explained in the visual below.

Multicellular life is built from incredibly organized components called cells, which cannot be properly compared to the simple clay things that are "building blocks." Even one-celled life is built from hundreds of different types of proteins, each a special arrangement of thousands of atoms that have to be organized just right, not something unordered like a building block.

We have this very misleading language by scientist Cabrol:

"This is life — or the building blocks of life — ever-present, but invisible to the human eye. Thanks to decades of astronomical research, we know these organic molecules and volatiles are found on Mars, in the plumes of Saturn’s tiny moon Enceladus, in the atmosphere of Titan, on comets and more."

The proteins required for life require very special arrangements of amino acids. But no amino acids have been found on Mars. This has been a giant investigative failure of astrobiologists, a flop. No building blocks of life have been found on Mars, but Cabrol sounds like someone attempting to insinuate that such things were discovered. Organic molecules are extremely rare on Mars, existing in only the scantiest amounts; and the only type of organic molecules found on Mars are not building blocks of life. The building components of visible life forms are cells; the building components of such cells are protein molecules; and the building components of protein molecules are amino acids. No one ever even found amino acids on Mars. So if you insist on using this term "building blocks," a correct statement would be: not even the building blocks of the building blocks of the building blocks of visible organisms have been found on Mars. There is no evidence of amino acids being found on Enceladus or Titan. Claims were made to have detected some amino acids in a sample retrieved from a comet, but the reported abundances were negligible, so low we can have no strong confidence in the claims, because of a high chance of earthly contamination (discussed here).

We then have these lines from Cabrol:

"Much farther away still, nearly 200 hundred types of prebiotic organic molecules have been detected over decades of astronomical observation in interstellar clouds near the center of our galaxy. They include the kinds of molecules that could play a role in forming amino acids — those building blocks of life."

Notice the "try to make a silk purse out of a sow's ear" language. We don't hear about the discovery of amino acids in interstellar clouds, but merely a mention of "molecules that could play a role in forming amino acids." It's like someone who doesn't have a best seller and doesn't have a finished book and doesn't have a first chapter and doesn't even have any paper saying that he has a tree in his back yard, and that the tree could be used to make paper.

We then have this utterly fallacious example of the "many chances equals many successes" argument that astrobiologists like to use:

"The sheer number of potential alien worlds adds to the probability that life could be abundant in the universe. Data received from Kepler space telescope missions since its launch in 2009 suggest that tens of billions of Earth-sized planets could be located in the habitable zone of sun-like stars in our galaxy alone.

Because the probability distribution in nature predicts more puddles than large lakes — more small buttes than Himalayas, more small planets than large ones and more simple life than complex life — the universe is likely teeming with planets harboring that simple life."

Such reasoning is completely fallacious. It is not at all true in general that "many chances equals many successes." It is also not at all true in general that "many chances equals some successes" or even that "many chances equals at least one success." If the probability of something happening is sufficiently low, then we should expect many chances to yield zero successes. So "many chances" does not necessarily equal "many successes," and "many chances" does not necessarily equal "some successes" or even one success. For example:

- If everyone in the world threw a deck of cards into the air 1000 times, that would be almost 10 trillion chances for such flying cards to form into a house of cards, but we should not expect that in even one case would the flying deck of cards accidentally form into a house of cards.

- If a billion computers around the world each made a thousand attempts to write an intelligible book by randomly generating 100,000 characters, that would be a total of a trillion chances for an intelligible book to be accidentally generated, but we should not expect that even one of these attempts would result in the creation of an intelligible book.

- If you buy a million tickets in a winner-take-all lottery in which the chance of winning is only 1 in 100 million, you should not expect that any one of those tickets will succeed in winning such a lottery.

- It is not necessarily true that many chances (also called trials) will yield many successes.

- It is not necessarily true that many chances (also called trials) will yield some successes or even one success.

- If the chance of success on any one trial multiplied by the number of trials gives a number less than 1, we should not expect that even one of the trials will produce a success.

- If the chance of success on any one trial multiplied by the number of trials gives a number greater than 1, we should expect that at least one of the trials will produce a success.

- "The transformation of an ensemble of appropriately chosen biological monomers (e.g. amino acids, nucleotides) into a primitive living cell capable of further evolution appears to require overcoming an information hurdle of superastronomical proportions (Appendix A), an event that could not have happened within the time frame of the Earth except, we believe, as a miracle (Hoyle and Wickramasinghe, 1981, 1982, 2000). All laboratory experiments attempting to simulate such an event have so far led to dismal failure (Deamer, 2011; Walker and Wickramasinghe, 2015)." -- "Cause of Cambrian Explosion - Terrestrial or Cosmic?," a paper by 21 scientists, 2018.

- "Biochemistry's orthodox account of how life emerged from a primordial soup of such chemicals lacks experimental support and is invalid because, among other reasons, there is an overwhelming statistical improbability that random reactions in an aqueous solution could have produced self-replicating RNA molecules." John Hands MD, "Cosmo Sapiens: Human Evolution From the Origin of the Universe," page 411.

- "The interconnected nature of DNA, RNA, and proteins means that it could not have sprung up ab initio from the primordial ooze, because if only one component is missing then the whole system falls apart – a three-legged table with one missing cannot stand." -- "The Improbable Origins of Life on Earth" by astronomer Paul Sutter.

- "Even the simplest of these substances [proteins] represent extremely complex compounds, containing many thousands of atoms of carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, and nitrogen arranged in absolutely definite patterns, which are specific for each separate substance. To the student of protein structure the spontaneous formation of such an atomic arrangement in the protein molecule would seem as improbable as would the accidental origin of the text of Virgil's 'Aeneid' from scattered letter type." -- Chemist A. I. Oparin, "The Origin of Life," pages 132-133.

- "The expected number of abiogenesis events is much smaller than unity when we observe a star, a galaxy, or even the whole observable universe." -- Scientist Tomonori Totani, "Emergence of life in an inflationary universe," a paper confessing we would not expect one natural origin of life (abiogenesis) even in the entire observable universe (link).

- "We now know not only of the existence of a break between the living and non-living world, but also that it represents the most dramatic and fundamental of all the discontinuities of nature. Between a living cell and the most highly ordered non-biological system, such as a crystal or a snowflake, there is a chasm as vast and absolute as it is possible to conceive." -- -- Michael Denton, MD and biochemistry PhD, "Evolution: A Theory in Crisis," page 250.

No comments:

Post a Comment