At the link here you can read a full transcript of the recent US Congress hearing on UFOs or UAPs, which occurred on July 26, 2023. Some government committee or group is currently using the term UAP, previously defining that term as Unidentified Aerial Phenomena and then later more broadly defining it as Unidentified Anomalous Phenomena. The testimony last Wednesday had some very interesting quotes, and it is testimony that seems to deserve very serious follow-up investigation. But while the testimony included some riveting second-hand testimony (in which witnesses described amazing things they said other people told them they saw), the testimony was light on compelling first-hand testimony, and featured no photographic evidence.

An astronomer named Adam Frank not long ago wrote an article for the New York Times with a title saying "U.F.O.s Don't Impress Me." Now Frank has written a response to the recent UFO testimony, one entitled "Here’s what a scientist makes of Congress’ UFO hearing." In the article Frank makes no mention of any of the more sensational quotes that came out of the hearing, which I quote in my previous post here. We may wonder whether Frank carefully reviewed the full testimony given. What we should remember is that the vast majority of scientists writing articles about the paranormal (outside of scientific journals) have never bothered to seriously study what they are writing about. So, for example, if you read a scientist article in Scientific American mentioning ESP or out-of-body experiences or apparition sightings, there will be a 90% chance the article was written by someone who has never bothered to seriously study such topics.

Frank's article starts out badly by giving us this quote which draws a conclusion that makes no sense:

"At their first press conference, held this summer, the team announced that only 6% of the many UAP cases they studied could not be explained. In other words, 94% of their UAP cases had earthly causes. This conclusion is consistent with other studies of this kind that have been done. So, it’s safe to say that the Earth is not suddenly awash in strange and unexplainable phenomena sailing through the skies. "

This reasoning is illogical. UAP means "Unidentified Aerial Phenomena" or "Unidentified Anomalous Phenomena." From a supposed estimate that only 6% of UAP reports are unexplained, we are not entitled to draw any conclusion at all about whether there are "strange and unexplainable phenomena sailing through the skies." On page 19 of the recent RAND Corporation report here, we read of "101,151 reported UAP sightings" in the United States between 1998 and 2022. So we may presume that the worldwide count of UFOs or UAP during that time was probably more than 500,000. Given so many UAP or UFO reports around the world, if 6% are unexplained that would still leave something like 30,000 sightings that could not be explained.

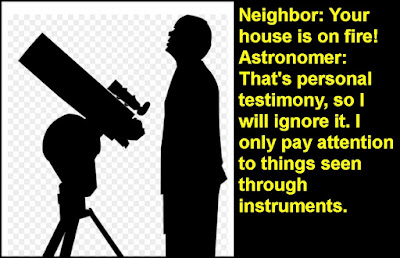

Frank then gives us the very goofy suggestion that scientists should not pay attention to personal testimony. He states this:

"While we could spend lots of time trying to figure out exactly what the pilots saw, I feel like that’s a dead end. Science cannot do much with personal testimonies. One problem, as every cop and psychologist will tell you, is that human memory is not a photographic record. Instead, it’s a reconstruction that can differ from the original event in many ways, no matter how earnest the reporters are. But what’s even more important, and as I describe more fully in the book, is that to really do science you need hard data collected through rational search strategies from instruments you fully understand."

This is a very silly thing for a scientist to say. Documenting, analyzing and classifying personal testimonies is one of the most important jobs of some types of scientists. The fact that human memories are not photographs does not excuse a scientist from the responsibility of documenting, analyzing and classifying personal testimonies. Frank's appeal here to cops (policeman) and psychologists is laughable, because documenting, analyzing and classifying personal testimonies is one of the most important job responsibilities of policeman and psychologists. The idea that you can only do science using "instruments you fully understand" is nonsense. A very large fraction of scientific data is gathered by scientists recording things seen with their eyes and heard with their ears, knowledge not obtained by using instruments such as telescopes and microscopes. There are very many things scientists can do with personal testimonies: publish them, summarize them, analyze them, classify them, corroborate them, quantify them, correlate them, index them, tag them, try to explain them, and ponder their consequences.

Only an astronomer would make the claim that you can only do real science using instruments. Astronomers spend their lives staring through telescopes or coldly analyzing data coming from space telescopes, involving objects in distant space. It's a great job for people who don't love dealing with other people. Anyone is entitled to such a career path if they want to pursue it, but we should heap scorn on such people if they ever try to evoke some "science is only done with instruments" principle, which is every bit as false as the claim that medicine is only done with instruments such as scalpels and X-ray machines.

The idea that some observation becomes more reliable when it occurs using metal instruments is not a sound one. The very introduction of such instruments often creates all kinds of additional possibilities for error, for maybe a scientist didn't use exactly the proper settings when using his fancy hi-tech instrument. For example, computerized telescopes have fancy interfaces for moving the telescope to an exact spot in the sky; and if you don't use such an interface just right, your telescope will end up pointing at the wrong little spot in the sky. And it is just as easy for scientists to commit very bad errors when using instruments as when using their unaided eyes. For example, nowadays we see a huge proliferation of poorly designed junk science fMRI bran scan studies producing mainly false alarms. All that junk science comes from scientists who used metal instruments.

In his next paragraph Frank speaks in an equally illogical manner, making this claim:

"If my colleagues and I ever want to claim that we have detected signatures of life on alien planets light-years away, we will have to know everything about our instruments: how they respond to light when the telescope is at 40°F and how that response changes when the temperature goes up to 60°. The exact same type of knowledge is required to determine whether a UAP accelerated in ways that no human technology could reproduce. Personal testimony, onboard targeting cameras, and even military radars cannot do that."

No, any of these things would be sufficient to tell whether a UFO accelerated in ways that no human technology could reproduce, given sufficient speed of the UFO. Frank seems to be making here some strange assumption that makes no sense. Is he evoking a principle that you can't know how fast something is moving unless you use some technology and fully understand that technology? That principle makes no sense. Anyone standing on the edge of a highway can estimate fairly reliably how fast a car is moving. And the police officers who use radar guns to reliably determine the speed of speeding cars often don't understand the details of their technology.

Frank then states this:

"There is no reason, based on any existing science, to take these truly stunning claims seriously. I’m not changing this position until somebody ponies up some actual artifacts (which I will note are always promised to be coming but never show up). In other words, show me the spaceship."

This sounds like Frank is evoking a principle of "ignore the evidence for something until you have conclusive evidence for that thing." Thankfully, scientists have never followed so senseless a rule, which would have prevented them from discovering most of the things they have discovered. The process of scientific discovery typically starts out with a scientist getting only weak signs or signals of something, what salesmen call "leads." If scientists follow up with years of additional diligent inquiry, they may end up getting proof of the thing or effect investigated. "Don't pay attention until you have conclusive proof" is a rule that would cripple science. I may note that if you wanted an example of a group of scientists who do not follow such a rule, and spend entire careers investigating unproven things based on weak evidence, you could not find a better example than Frank's own group of scientists: astronomers. The modern astronomer spends a good fraction of his time trying to prove the existence of dark matter and dark energy, mysterious things that have never been directly observed.

We should also note the strangeness of Frank's claim "There is no reason, based on any existing science, to take these truly stunning claims seriously." Astronomers such as Frank frequently try to persuade us that extraterrestrial life exists, based on the large number of extrasolar planets that astronomers have discovered. In fact, later in the article Frank says, "I know that the astronomical telescopes, technologies, and techniques coming online now mean we will soon be able to sniff out life in the atmospheres of alien worlds." If we accept the claims that people such as Frank make, that would provide a very large reason, based on existing science, why one should take seriously claims of extraterrestrial visitors, and diligently investigate such claims.

I may note that the claim by Frank just quoted is an untrue one. He certainly does not "know that the astronomical telescopes, technologies, and techniques coming online now mean we will soon be able to sniff out life in the atmospheres of alien worlds." Even the simplest life is a state of organization so vast that we should never expect life to arise by chance chemical combinations even given billions of planets in each of billions of galaxies. The simplest self-reproducing cell requires something like 90,000 very well-arranged amino acids (consisting of a total of roughly a million very well-arranged atoms), and the chance of getting that from chance events is very much like the chance of typing monkeys producing a grammatical, well-written 300-page instruction book. It is possible that there is very much life in the universe, but only if some purposeful agency is at work to help produce such life. If the origin-of-life dice are not "loaded" to overcome the prohibitive odds against natural abiogenesis, it is improbable that life exists elsewhere in our galaxy, and improbable that life will be discovered on another planet anytime in this century. We have in the quote above a very good example of something that is constantly occurring: scientists claiming that they know things they do not at all know.

Frank claims to "know that the astronomical telescopes, technologies, and techniques coming online now mean we will soon be able to sniff out life in the atmospheres of alien worlds." He's talking about things like the James Webb Space Telescope. That telescope has already been operating for 20 months, and has not succeeded in sniffing out life or discovering life. There's no particular reason to be optimistic that it will be able to do in the near future what it failed to do in the first 20 months of its existence.

Another astronomer who has given us scrambled reasoning about UFOs is astronomer Seth Shostak, who has spent decades heaping scorn on people who claim to see unidentified things in the sky. It would be a rather pessimistic but at least an internally consistent position for someone to maintain (based on the extremely high organization and functional complexity of even the simplest living cell) that extraterrestrial life is extremely rare or nonexistent, and that we therefore should not expect to be getting visitors from other planets. That's not what's going on with Shostak. He is supremely optimistic about the number of extraterrestrial civilizations in our galaxy (maintaining "our galaxy should be teeming with civilizations"), but seems likes someone always heaping scorn on the idea that any such civilization might have recently visited our planet.

Shostak's essays on this UFO topic always seems like hasty armchair reasoning rather than the work of a careful scholar of anomalous things in the sky. He gives the impression of someone who cannot be bothered to get his hands dirty by closely investigating individual observational cases. In an article entitled "Aliens There But Not Here," Shostak gives some extremely bad armchair reasoning. First, he tries to insinuate that traveling between solar systems is too difficult. He tells us that having an interstellar rocket would require "100 million times as much energy as a NASA rocket." But that's no reason for skepticism, as an extraterrestrial civilization much older than ours could surely make rockets using that much energy. Then he makes this ridiculous objection: "High velocity travel though space means bulldozing through the dust and gas that bathe our galaxy at a blistering pace, turning it into tiny bullets that will pierce the hull of any rocket and quickly dispatch the biology within." Galactic dust has only very sparse densities, and is concentrated in dust clouds, which could easily be avoided by an interstellar spacecraft. And even if traveling through dust so sparse, a technology vastly older than ours could easily deflect such dust, or simply build ships with hulls strong enough to not be damaged by it. Shostak very strangely seems to think that a hull of a starship built by extraterrestrials with godlike powers would not be strong enough to protect against "tiny bullets." He then tries to insinuate that imagining interstellar visitors requires postulating new physics, saying, "Presumably, extraterrestrial visitors have mastered something akin to warp drive or breaking into hyperspace." No, it is well-known that there are relatively simple spacecraft construction techniques that would be capable of traveling between stars, such as building a multi-generation starship or building a starship populated by robots or creatures with very long lifespans or creatures extending their lifetimes by using hibernation techniques. Such possibilities do not require any "new physics" things such as warp drives or hyperspace travel.

The next part of Shostak's article is equally fallacious. He attempts to insinuate that there's something implausible about us getting interstellar visitors now, because we didn't get them in the nineteenth century. That makes about as much sense as arguing, "He couldn't have traveled to Chicago in 2017, because he didn't go there in 2016."

Of course, there's a perfectly good answer to such an objection, one that mentions how Earth has been leaking radio signals for many decades, that would have alerted nearby civilizations to our existence. Such signals have escaped Earth for about 75 years, meaning (allowing for a near-lightspeed travel) that stars within about about 37 light years might be more likely to be the home planets of interstellar visitors. Shostak's answer to this objection is scrambled logic:

"The simple fact is that there are fewer than two thousand stars within thirty-seven light-years. It beggars belief to say that the cosmos is so densely packed with aliens that some are camped out so near to us. If you assume that there are between one and 100 million alien societies in our home galaxy now (an optimistic estimate), then the closest would be a few hundred lightyears’ distant. They won’t know about us."

Shostak's logic here is very bad. Making completely arbitrary estimates of the number of civilizations in our galaxy (estimates which have an uncertainty factor ranging from about 10,000 on the upside to about 100,000,000 on the downside), Shostak is arguing here that the galaxy must have just about as many extraterrestrial civilizations as he thinks, and not ten times more or 100 times more. Given the very large uncertainties, such logic makes no sense even before we consider the issue of interstellar colonization. Once we consider that issue, we can see Shostak's logic as being worthless. Once one civilization arose in one solar system, there would be a good chance that it might spread around to many other solar systems, something that can be called interstellar colonization. So if you estimated that intelligent life naturally arose on 100 million planets in our galaxy, and if you pay attention to the possibility of interstellar colonization, then you should think that there are now many billions of inhabited planets in our galaxy, because of the tendency of intelligent life to spread from one solar system to another. Once you get that estimate, then you get extraterrestrial civilizations within 37 light-years of Earth.

I mention these points merely to rebut Shostak's reasoning on this matter, not because there is any need why a believer in spaceships from other planets visiting today's Earth needs to defend the idea that an extraterrestrial civilization would exist within 37 light-years of Earth or 100 light-years of Earth. A civilization vastly more advanced than ours would be able to build multi-generation starships capable of traveling many hundreds or thousands of light-years, in voyages lasting very many generations. The very hard part is getting life on a planet, and then getting civilized intelligent life. Creating ships that can cross many light years (once you already have an interplanetary civilization) is child's play, relatively speaking.

It seems that when mainstream scientists other than parapsychologists write about the paranormal, they usually give us their laziest efforts, failing to be diligent in either scholarship or logic. It's as if their rule was: when writing about the paranormal, just "phone it in." An example of the lazy responses scientists have given to the US Congress UFO hearing is a tweet by physicist Brian Cox, in which he stated, "I watched a few clips and saw some people who seemed to believe stuff saying extraordinary things without presenting extraordinary evidence." How very lazy, to scold people based on impressions got after you just "watched a few clips" rather than watching the entire hearing (easily available on youtube.com) or reading a full transcript of the testimony.

Postscript: Seth Shostak has written another anti-UFO article. I guess he has time for this because nothing much is going on in his fruitless field of searching for radio signals from extraterrestrials. In the article Shostak gives us another example of defective astronomer reasoning on UFOs. He states this:

"There are thousands of satellites orbiting Earth. The majority sport cameras aimed downward. Actual alien craft in our airspace bigger than an office desk would likely be visible to satellites that — among other things — supply imagery to Google Earth. "

No comments:

Post a Comment