A scientist in 1944 could have been certain that a nuclear bomb exploded in space would have only caused a limited chain reaction, because eventually neutrons traveling out from the explosion would run into the vacuum of space, causing the nuclear chain reaction to stop. But the earth's atmosphere is not a vacuum. It has many atoms of oxygen and nitrogen. So a scientist around 1944 must have been worried about a terrifying possibility: that a nuclear bomb exploded in the atmosphere would cause a chain reaction that would keep spreading throughout the atmosphere, being fueled by the atoms of oxygen and nitrogen in the atmosphere.

One scientist named Hans Bethe thought that such an ignition of the atmosphere was impossible. But we are told on page 276 of Ellsberg's book, “[Enrico] Fermi, in particular, the greatest experimental physicist present, did not agree with Bethe's assurance of impossibility.” On page 279 Ellsberg states, “Nearly every account of the problem of atmospheric ignition describes it, incorrectly, as having been proven to be a non-problem – an impossibility – soon after it first arose in the initial discussion of the theoretical group, or at any rate well before a device was actually detonated.” On page 280 Ellsberg quotes the official historian of the Manhattan Project, David Hawkins:

"Prior to the detonations at the Trinity site, Hiroshima, or Nagasaki, Hawkins told me firmly, they never confirmed by theoretical calculations that the chance of atmospheric ignition from any of these was zero. Even if they had, the experimentalists among them would have recognized that the calculations could have been in error or could have failed to take something into account."

The second part of this quote makes a crucial point. Anyone with engineering experience knows that there is usually no way that you can prove on paper that some engineering result will happen or will not happen. The only way to have confidence is to actually do a test. An engineer can go over some blueprints of a bridge with the greatest scrutiny, but that does not prove that the bridge will not collapse when heavy trucks roll over it. A software engineer can subject every line of his source code to great scrutiny, but that does not prove that his program will not crash when users try to use it. When you are doing very complex engineering, the only way to discover whether something bad will happen is by testing. So the idea that the nuclear engineers did some calculations to make them confident that the atmosphere would not explode is erroneous. They could have had no such confidence until a nuclear bomb was actually tested in the atmosphere.

According to one source Ellsberg quotes on page 281, Enrico Fermi (one of the the top physicists working on the atomic bomb) stated the following before the test of the first atomic bomb, referring to an ignition of the atmosphere that would have killed everyone on Earth:

"It would be a miracle if the atmosphere were ignited. I reckon the chance of a miracle to be about ten percent."

Apparently the atomic bomb scientists gambled with the destruction of all of humanity. There is no record that the scientists ever informed any US president about the risk of atmospheric ignition. After the first atomic bomb was tested in 1945, scientists got busy working on a vastly more lethal weapon: the hydrogen bomb. When the first hydrogen bomb was exploded in 1952, with a destructive force a thousand times greater than that of the first atomic bomb, the ignition of the entire atmosphere (or some similar unexpected side-effect) was again a possibility that could not be excluded prior to the test. Again, our physicists recklessly proceeded down a path that (for all they knew) might well have destroyed every human. Even if you ignore the risk of an atmospheric detonation, there was a whole other reason why scientists were gambling with mankind's destruction: the fact that there is always a risk of a nuclear holocaust in a world packed with H-bombs.

Following the invention of the hydrogen bomb, the number of nuclear weapons grew larger and larger, until about the 1980's when there were some 50,000 nuclear weapons in the world. Thankfully the number of nuclear weapons has declined since then. But we still all live under the threat that billions may be killed because of the nuclear bombs that scientists invented. And now there is another danger of many millions or even billions dying from the work of scientists: the danger of a pandemic worse than COVID-19 coming from reckless scientific experimentation with bacteria and viruses.

Fears about such a topic are mentioned in a recent Washington Post article with the title "Lab-leak fears are putting virologists under scrutiny." The article refers us to an editorial of the American Society for Microbiology which makes it sound like microbiologists have zero interest in making their activities safer. The editorial endorses gain-of-function research in which viruses or bacteria are artificially engineered to improve their deadliness. We read this about such gain-of-function research: "We should clearly delineate the benefits of the research that we perform, including explaining why GOF [gain-of-function] is the preferred approach to reaping those benefits in those cases where it is." The editorial attempts to reassure us by saying, "We must acknowledge that not every gain-of-function experiment carries the risk of global catastrophe." So this is supposed to reassure us, that when virologists monkey with virus genomes they are not always risking a global catastrophe? That sounds about as reassuring as a son saying, "Mom, don't worry about me playing Russian Roulette -- sometimes when I play the gun has no bullets."

We then have in the Washington Post article this piece of misleading speech trying to justify perilous gain-of-function research:

"To probe the coronavirus’s secrets requires experiments that may involve combining two strains and seeing what happens. The creation of recombinant or chimeric viruses in the laboratory is merely mimicking what happens naturally as viruses circulate, researchers say. 'That’s what viruses do. That’s what scientists do,' said Ronald Corley, the chair of Boston University’s microbiology department and former director of NEIDL."

No, viruses are not intelligent agents, and do not perform experiments combining the genomes of two different microbes for the sake of "seeing what happens." And viruses don't have fancy technologies such as CRISPR allowing them to create exactly whatever Frankenstein-style microbe they wish to create. The Washington Post article then tells us, "Experiments in the United States and the Netherlands created versions of the H5N1 influenza virus that could be more easily transmitted among ferrets," and that as a result of this "The National Science Advisory Board for Biosecurity warned of a possible 'unimaginable catastrophe.' "

But then we have a virologist who makes it sound like the biggest problem is that people are worried about gene-splicing virologists unleashing such horrors on the world. The virologist says, "I knew the world was crazy, but I hadn’t exactly realized how crazy." But why would it be crazy to have such perfectly reasonable concerns?

The Washington Post article then attempts to convince us that gene-splicing gain-of-function virus laboratories in the US are safe, telling us this:

"The NEIDL is basically a fortress. Hundreds of security cameras are sprinkled through the building, along with motion sensors and retina scanners...'I feel safer working in this building than being out on the streets walking around,' said Corley, suggesting he would be more likely to catch a bad virus outside than while working among pathogens in his laboratory."

So what is the idea here, that the security cameras and motion sensors and retina scanners are supposed to catch escaping invisible viruses? That's the funniest joke I've heard this month. As for Corley's inner feelings, they don't have any weight in the world of science, where safety should be measured by things that are numerically quantifiable.

A 2015 USA Today article entitled "Inside America's Secretive Biolabs" discussed many severe problems with safety in such pathogen research labs, telling us this:

"Vials of bioterror bacteria have gone missing. Lab mice infected with deadly viruses have escaped, and wild rodents have been found making nests with research waste. Cattle infected in a university's vaccine experiments were repeatedly sent to slaughter and their meat sold for human consumption. Gear meant to protect lab workers from lethal viruses such as Ebola and bird flu has failed, repeatedly.

A USA TODAY Network investigation reveals that hundreds of lab mistakes, safety violations and near-miss incidents have occurred in biological laboratories coast to coast in recent years, putting scientists, their colleagues and sometimes even the public at risk.

Oversight of biological research labs is fragmented, often secretive and largely self-policing, the investigation found. And even when research facilities commit the most egregious safety or security breaches — as more than 100 labs have — federal regulators keep their names secret.

Of particular concern are mishaps occurring at institutions working with the world's most dangerous pathogens in biosafety level 3 and 4 labs — the two highest levels of containment that have proliferated since the 9/11 terror attacks in 2001. Yet there is no publicly available list of these labs, and the scope of their research and safety records are largely unknown to most state health departments charged with responding to disease outbreaks. Even the federal government doesn't know where they all are, the Government Accountability Office has warned for years."

You should read the entire USA Today article. It will give you the chills. We read of the pathogen death of a researcher in a lab, and we read this:

"A lab accident is considered by many scientists to be the likely explanation for how an H1N1 flu strain re-emerged in 1977 that was so genetically similar to one that had disappeared before 1957 it looked as if it had been 'preserved' over the decades. The re-emergence 'was probably an accidental release from a laboratory source,' according to a 2009 article in the New England Journal of Medicine."

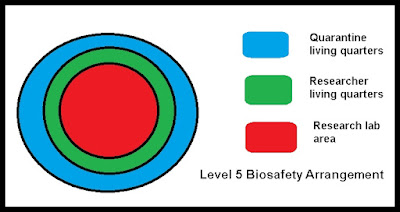

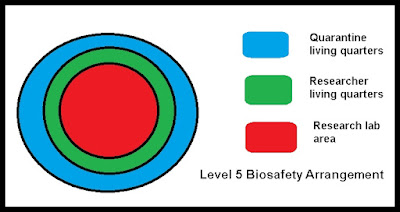

There is a system for classifying the security of pathogen labs, with Level 4 being the highest level currently implemented. It is often claimed that Level 4 labs have the highest possible security. That is far from true. At Level 4 labs, workers arrive for shift work, going home every day, just like regular workers. It is easy to imagine a much safer system in which workers would work at a lab for an assigned number of days, living right next to the lab. We can imagine a system like this:

Under such a scheme, there would be a door system preventing anyone inside the quarantine area unless the person had just finished working for a Research Period in the green and red areas. Throughout the Research Period (which might be 2, 3 or 4 weeks), workers would work in the red area and live in the green area. Once the Research Period had ended, workers would move to the blue quarantine area for two weeks. Workers with any symptoms of an infectious disease would not be allowed to leave the blue quarantine area until the symptoms resolved.

There are no labs that implement such a scheme, which would be much safer than a Level 4 lab (the highest safety now used). I would imagine the main reason such easy-to-implement safeguards have not been implemented is that gene-splicing virologists do not wish to be inconvenienced, and would prefer to go home from work each night like regular office workers. We are all at peril while they enjoy such convenience. Given the power of gene-splicing technologies such as CRISPR, and the failure to implement tight-as-possible safeguards, it seems that some of today's pathogen gene-splicing is recklessly playing "megadeath Russian Roulette."

Don't worry a bit -- their offices have security cameras

Even when they don't deal with pathogens, gene-splicing scientists may create enormous hazard. The book Altered Genes, Twisted Truth by Steven M. Druker is an extremely thorough look at potential hazards involving genetically modified organisms (GMOs). The book has been endorsed by more than 10 PhD's, some of which are biologists. Here is a rather terrifying passage from page 192 of the book:

"Accordingly, several experts believe that these engineered microbes posed a major risk. Elaine Ingham, who, as an Oregon State professor, participated in the research that discovered those lethal effects, points out that because K. planticola are in the root system of all terrestrial plants, it is justified to think that the commercial release of the engineered strain would have endangered plants on a broad scale – and, in the most extreme outcome, could have destroyed all plant life on an entire continent, or even on the entire earth...Another scientist who thinks that a colossal threat was created is the renowned Canadian geneticist and ecologist David Suzuki. As he puts it, 'The genetically engineered Klebsiella could have ended all plant life on the continent.' ”

No comments:

Post a Comment