There are two numbers used nowadays to judge the performance of a scientist: a paper count representing the number of papers published, and a citation count representing the number of citations such papers count (each such citation being a reference to a paper occurring in some other paper). There are five sleazy ways in which the modern scientist may attempt to increase these numbers.

Method #1: Author Inflation

Over the decades there has been a phenomenon under which the average number of authors listed on a scientific paper has grown higher and higher. A paper this year states the following:

"Escalating author counts in science are a longstanding phenomenon. The average number of authors per published article has risen steadily for decades. From the 1930s to the 1970s, the average number of authors on a published article was 2 and since then has escalated sharply. Between 1970 and 2010, the number of articles with 6 to 10 authors increased more than 10-fold. By 2000, the average number was 7, and the number of articles with 11 to 20 authors increased more than 20-fold. Multiauthorship (more than 10 authors) and hyperauthorship (more than 100 or even 1,000 authors) are now common."

What is going on is that more and more names are wrongly being listed as authors of scientific papers, so that scientists can brag about higher numbers of papers they authored. The problem is referred to by the euphemistic term "author inflation," although it really should be plainly called "lying about authorship." Referring to metrics such as the number of papers a scientist has authored and the number of citations such papers have got, the same paper states, "The pressures from institutional metrics have spawned an entire ecology of academic misconduct and manipulation."

A 2015 anonymous article is entitled, "My professor demands to be listed as an author on many of my papers." Describing a culture in which a type of deceit has been normalized, the author writes this:

"There’s one instance where it’s acceptable for scientists to lie: when fraudulently claiming authorship of a paper. Too often, researchers attach their names to reports when they have contributed nothing at all to the work. The problem gets worse the higher up the academic ladder you go."

This type of deceit works both ways. A scientist who had no real role in the production of a paper may pressure a junior scientist into adding him as an author. Or, the real author of the paper may add the senior scientist as an author, in hopes of increasing his chance of getting the paper published.

A paper distinguishes between "gift authorship" and "guest authorship," both of which involve putting names on the author list of scientific papers when the people did not help write the paper:

"Gift authorship may involve reciprocating favors for previous co-authorships (quid pro quo), helping a colleague obtain tenure or promotion, for romantic favors extended, or to assist the graduate student who might have only provided minimal administrative assistance to assist the student’s job search. In some cases, a colleague’s name is added on the understanding that s/he will do the same simply to swell an individual’s publication list.... Another form, guest authorship, may be used for multiple purposes, including the belief that by adding a well-known name the guest will increase the likelihood of publication, credibility, or status of the work, or to conceal a paper’s industry ties by including an academic author....Interestingly, research conducted by Eastwood, Derish, Leash, and Ordway (1996) found one-third of respondents would credit an author who had not contributed to the publication. Typically, this is done in order to increase the likelihood of the research being accepted for publication or in other cases, as a means to promote their career."

Another scientific paper gives us some idea about how common misleading "guest authorship" is:

"Guest authorship has been defined as 'the designation of an individual who does not meet authorship criteria as an author.' Guest authorship includes the practice of naming as authors individuals in senior positions (e.g., the director of a laboratory) in recognition of their perceived 'support' of the project, even if they did not contribute to conducting the study or writing the paper (sometimes referred to as 'honorary authorship'). Guest authorship has been found in 16% of research articles, 26% of review articles, 21% of editorials, and 41% of Cochrane reviews."

From the figures above we can make a plain deduction: gigantic numbers of scientists are claiming to have co-authored papers they did not actually co-author. We should not assume that a "guest author" is not aware that he has been listed as a co-author of paper he did not co-write. We should assume that the "guest author" is complicit in the fraud.

Method #2: Counting All Papers You've Authored or Co-Authored As Papers You've Written

The most outrageous type of misstatement involving the authorship of scientific papers occurs when scientists make patently misleading summaries of how many scientific papers they have written, something which happens very often. There are two rules of honest communication that apply to summarizing your contribution to scientific papers:

(1) A scientist should claim to have "authored" or "written" a scientific paper if and only if he or she is the sole author of that paper.

(2) In all other cases (such as there being two or more authors) the scientist should only claim to have co-authored or co-written the paper.

Any violation of these rules is dishonesty plain and simple. For example, if a scientist has solely authored 50 papers and co-authored 100 papers, it is blatantly dishonest for the scientist to claim that he has "authored 150 scientific papers" or "written 150 scientific papers." Such a claim creates in the reader the idea that the scientist is the sole author of 150 papers, when he was the sole author of only 50 papers. There is only one honest way for a scientist to describe such a situation: to make a statement such as "I have authored 50 scientific papers and co-authored 100 scientific papers."

A check of the web page of a high-profile Harvard scientist finds the claim that the scientist has written "about 800 papers." Following the link that appears with this statement, we find that almost all of these papers were not solely written by the scientist, but were co-authored or merely partially authored by the scientist. In most of these papers the scientist is not listed as the primary author. Accordingly the claim that the scientist has written "about 800 papers" is extremely misleading. Innumerable similar examples could be provided of scientists who misled us about the number of scientific papers they authored, by creating the idea that they were the main author of a certain number of papers, when they were only the main author of a small fraction of that number of papers.

It is easy to find very many similar examples of scientists lying to us about how many scientific papers they have authored, by just doing a Google search for phrases such as these:

"author of more than 300 scientific papers"

"author of more than 400 scientific papers"

"author of more than 500 scientific papers"

"author of more than 600 scientific papers"

"author of more than 700 scientific papers"

"author of more than 800 scientific papers"

It will generally be found that the scientist referred to did not individually author even half of the number of papers cited, and it will be very often found that the scientist was not even the primary author of half of the number of papers cited.

We can use the term "schlock for stats" for the extremely common practice of producing worthless junk papers, mainly for the sake of increasing an author's paper count. "Schlock" is a word meaning "cheap or inferior goods or material; trash." There are many types of schlock scientific papers being produced these days. Some examples:

- Cosmology papers which involve some excessively speculative, enormously improbable and impossible-to-verify scenario, which is described in incomprehensible mathematical formulas, without the writer even bothering to tell us what the obscure mathematical symbols mean.

- Very many evolutionary biology papers involving only unverifiable and extremely far-fetched speculations about things that might have happened hundreds of millions of years ago, often postulating events astronomically improbable or impossible because of limitations of DNA.

- Speculative chemistry papers giving chemical reaction equations only worked out on a blackboard, with the possibility of such reactions never even physically tested.

- Neuroscience papers describing poorly designed experiments that used Questionable Research Practices, meaning the papers fail to provide robust evidence for anything.

- Innumerable papers on topics of no importance.

- Innumerable papers so filled with jargon or obscure mathematics that they cannot be comprehended by anyone outside of some very tiny group of professors.

An extremely common practice nowadays is for scientific papers to make inaccurate claims in their titles and abstracts, claims not actually matching anything in the paper below such titles and abstracts. Scientists sometimes confess to doing this. At a blog entitled "Survival Blog for Scientists" and subtitled "How to Become a Leading Scientist," a blog that tells us "contributors are scientists in various stages of their career," we have an explanation of why so many science papers have inaccurate titles:

"Scientists need citations for their papers....If the content of your paper is a dull, solid investigation and your title announces this heavy reading, it is clear you will not reach your citation target, as your department head will tell you in your evaluation interview. So to survive – and to impress editors and reviewers of high-impact journals, you will have to hype up your title. And embellish your abstract. And perhaps deliberately confuse the reader about the content."

A study of inaccuracy in the titles of scientific papers states, "23.4 % of the titles contain inaccuracies of some kind."

Method #5: Self-Citation and Inappropriate Citation

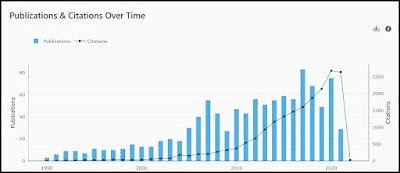

Self-citation is what happens when some author cites scientific papers that he authored or co-authored, probably to increase his paper citation count. Self-citation is frowned upon, but extremely common.

Inappropriate citation is when some scientific paper cites some other paper as support for some claim, when the paper does not actually support such a claim. A recent scientific paper entitled "Quotation errors in general science journals" tried to figure out how common such misleading citations are in science papers. It found that such erroneous citations are not at all rare. Examining 250 randomly selected citations, the paper found an error rate of 25%.

We can reasonably suspect a sleazy "old boy network" at work here, in which Professor X has lots of professors he has encouraged to cite his papers (regardless of whether the citation is appropriate), with the understanding that such a favor will be reciprocated by that professor citing the papers of those professors (regardless of whether such citations are appropriate).

We read here, "According to one estimate, only 20 per cent of papers cited have actually been read." Clearly there is a gigantic amount of sleazy citation going on the sake of artificially ballooning citation counts.

No comments:

Post a Comment