Imagine you had a kind of wacky uncle who was a member of some strange cult or online community believing that weather effects are produced by foreign interventions. So you might have conversations like this:

John: Uncle Bill, how was the weather when you went outside?

Bill: Today those Russian satellites trying to burn us to death are working pretty good. So it's very hot outside.

And on another day, you might have a conversation like this:

John: Uncle Bill, how was the weather when you went outside?

Bill: Today the Iranians are causing a lot of trouble with their secret wind machines. So it's very windy.

After a while, you might formulate a strategy for getting weather information from your uncle: simply be skeptical of what he says about causes, but pay attention to exact details he reports. So then you might have a conversation like this:

John: Uncle Bill, when I go outside should I wear just a light jacket?

Bill: Today those Mongolian cloud-seeding efforts are working well, and there's heavy rain.

John: Got it, Bill: it's raining, so I'll wear a rain coat.

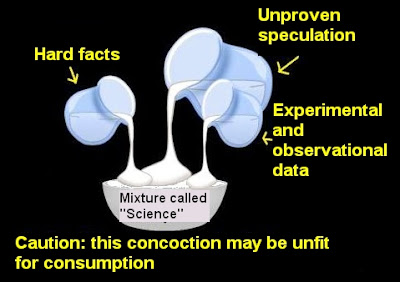

Like Uncle Bill who has bad ideas about causality because he belongs to a cult or cult-like social group, today's professors often belong to cult-like ideology factions that have taken root in our colleges and universities. The statements of scientists are so often polluted with dubious causal claims that when we read scientist statements, we need to follow a strategy rather like the one I just mentioned. We should very often be skeptical when scientists talk about causes, but have a fairly good trust of precise observational details that they report. So, for example, a good response to a scientist might be a conversation like this:

Frank: Hi, professor, what have you been up to?

Dave: I'm doing experiments showing that when brains produce new ideas, they are sometimes derived from previous memories stored long ago in synapses.

Frank: Got it, professor: you're doing some experiments merely showing that new ideas seem to be sometimes inspired by old memories.

Here Frank wisely throws away the unfounded causal claims that Dave has made, and extracts only the observational details that Dave has reported. Sadly, we need to do something similar when reading so many scientist statements: discard the unfounded causal claims that pollute such statements, and trust fairly well the exact observations reported. So, for example, if a scientist tells us that a "fossil of a human ancestor was found and dated to three million years," we should discard the superfluous and unfounded claim about human ancestry, and say: "Got, it professor: you found an old bone that you dated to be three million years old."

I say that we should "trust fairly well" the observational details reported by professors, rather than saying that we should assume such details are correct. Unfortunately, the tendency of professors to misspeak is so widespread that we cannot even take for granted any low-level observational report claim coming from them, particularly when such reports are not well replicated, or when they are reports of trace effects or marginal effects or hard-to-detect things, or when they are vague observational claims that lack numerical precision, or when they are reports of something observed after extensive playing around with statistical methods.

So, for example, when a scientist reports observing very tiny trace amounts of phosphine in the clouds of Venus, we should merely believe in the possibility of such an observation report being correct, rather than assuming the observation report is correct. That's because there is a very large tendency for ideologically biased observers to see whatever they wanted to see, and sometimes report observations of things that were not there. As discussed here, scientists have a hundred ways to conjure up illusory phantasms, each some little trick that might lead a scientist to report an observation of something that is not really there.

Below are general rules for parsing statements by professors:

(1) Be skeptical of most claims using phrases such as "scientists know" or "scientists have learned," since it is extremely common for people to claim that scientists know or have learned things they do not know or have not learned.

(2) Similarly, be skeptical of most claims using phrases such as "we know" or "it is well known," since it is extremely common for people to claim that humans know or have learned things they do not know or have not learned.

(3) Be particularly skeptical of any claim using a phrase such as "it is generally believed" or "most scientists believe," since such weak-sounding phrases are often used about claims that are not well-supported by evidence.

(4) Be skeptical of any claim that some particular scientist showed something, and realize that such claims are very often mere achievement legends.

(5) Be skeptical of any claim that is based on a single experiment or a single paper, realizing that reports of novel observational results very often or usually fail to be replicated by those trying to replicate the result.

(6) Be skeptical of all appeals to a scientific consensus, and realize that when most such claims are made, there is no reliable evidence that such a consensus exists. The only way to reliably measure the beliefs of scientists is to do secret ballot polls, but such secret ballot polls are almost never done.

Let us consider a very interesting type of alleged consensus that I may call a "leader's new clothes" consensus. Let us imagine a small company of about 20 employees that has a weekly employee meeting every Monday morning. On one Monday morning after all the employees have gathered in a conference room for the meeting, the company's leader comes in wearing flashy new clothes that are both very ugly and ridiculous-looking. Immediately the leader says, "I just paid $900 for this new outfit -- raise your hand if you think I look great in these clothes."

Now if it is known that the leader is someone who can get angry and fire people for slight offenses, it is quite possible that all twenty of the employees might raise their hand in such a situation, even though not one single one of them believes that the leader looks good in his ugly new clothes. In such a case the "public consensus" is 100% different from the private consensus. A secret ballot would have revealed the discrepancy.

The point of this example is that appeals to some alleged public consensus are notoriously unreliable. So arguing from some alleged consensus of some group is a weak and unreliable form of reasoning. The only way to get a reliable measure of the opinion of people on something is to do a secret ballot, and nobody does secret ballots of scientists asking about their opinions on scientific matters. We have no idea of whether the private beliefs of scientists differ very much from the public facade they present. For example, we have no idea whether it is actually true that most scientists think your mind is merely the product of your brain. It could easily be that 55% of them doubt such a doctrine, but speak differently in public for the sake of avoiding "heresy trouble" and seeming to conform to the perceived norms of their social group.

No comments:

Post a Comment