On page 27 of the book Miller refers to the “evolutionary priesthood,” but he makes clear in his book that he wants us to believe in the dogmas of this priesthood. If you're going to confess that some doctrine is being advanced by a priesthood, and if you're going to say as Miller does on page 29 that “perhaps, as some will say, the Darwinian story is a house of cards,” then you better give good evidence to back up that priesthood's catechism.

In this regard Miller is not terribly successful. His argument that humans and chimpanzees share a similar ancestor is based on some embryo and chromosome evidence that is murky indeed, at least in Miller's exposition of it. The book attempts no substantive general justification of the claim that very complex biological innovations can appear because of natural selection and random mutations, a claim for which there is still no convincing evidence. We still have no proof that any complex biological innovation ever appeared because of such things.

On page 124 Miller attempts some reasoning to support the idea that brains can produce minds. He says this:

Groups of neurons can act something like switches as well...So, speaking simplistically, neurons indeed mimic the functions of transistors, and therefore it's plausible to think of the brain as a huge collection of neural circuits in the same way that a modern computer is a similar collection of electrical circuits....The image of brain as computer is compelling enough that many have been willing to use that model to explain the workings of the brain, including thought, as phenomena completely explicable in terms of biochemistry and cell biology.

But there are some reasons why this comparison is a poor one. They include the following:

- Computers don't actually have consciousness,

understanding or mental experiences like humans have.

- Computers have very clear read-write mechanisms,

and a very clear permanent storage place (a hard drive), but we

can't find any clear signs of such things in the brain, as it seems

to have no place suitable for storing memories longer than a year,

no mechanism for writing memories, and no mechanism for reading

memories.

- Computers are deliberately designed products,

but evolutionary biologists want us to believe that brains are not

designed products.

- If computers just consisted of electrical

circuits, they wouldn't be able to do anything. Computers can do

some things because they have lots of deliberately designed

software, something which has no counterpart in the human brain.

Genes are not true software, and are certainly not anything like

programs for thinking.

So it seems that the “brain is a computer” comparison doesn't work well at all.

On pages 131 to 134 Miller begins to address an argument made by Alfred Russel Wallace, the co-originator (along with Darwin) of the theory of natural selection. Wallace argued that natural selection is very much inadequate to account for the features and capabilities of the human mind. The problem is that humans have all kinds of refined capabilities that would not have done humans any good from the standpoint of natural selection, in that they would not have increased a human's likelihood of survival or reproduction in the wild. You can read Wallace's original argument here. Among the capabilities that we can list as being inexplicable from the standpoint of natural selection are spirituality, aesthestic appreciation, artistic creativity, mathematical ability, philosophical reasoning ability, refined language capabilities, curiosity, musical capabilities, wonder, insight, imagination and moral sensibilities. Read here for an extended explanation of why such things would have not increased a human's likelihood of surviving and reproducing, and are therefore not explicable from a Darwinian standpoint of natural selection. As Wallace stated, "Natural Selection could only have endowed savage man with a brain a little superior to that of an ape, whereas he actually possesses one very little inferior to that of a philosopher."

Miller has an answer to such reasoning – a very weak answer. His answer is that such things are evolutionary spandrels. What is a spandrel? The term was first used in a biological context by paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould. He said that spandrels were an architectural feature in domed architecture that were never specifically designed to exist, but arose as just kind of a by-product of other features that were designed for specific reasons. He proposed that we could start using this term “spandrels” in a biological context in this way: whenever we found some feature or capability of humans that would not have been favored by natural selection, we could call that feature a spandrel, and describe it as a by-product of some other feature that would be favored by natural selection.

A person such as Miller who uses this type of reasoning may argue that we developed big brains so we could be better at hunting, and that most of our mental abilities are just by-products of the fact that we have such big brains. On page 162 Miller says, “Wallace's concern...is effectively answered by the concept of evolutionary spandrels.”

There are numerous problems with this type of reasoning, which include the following:

- Any comparison between architectural spandrels

and human characteristics is inappropriate for an evolutionary

biologist maintaining that humans are not the product of design. If

you don't believe humans are the product of design, what business do

you have referring to accidental products in human architecture that

is a product of design?

- When something is plausibly explained as a

by-product of something else, we can give an exact explanation of

why the by-product would occur, given that something else. For

example, a solar physicist could give an exact explanation of why

solar flares would occasionally occur as a by-product of

thermonuclear fusion in the sun; and anyone familiar with the

kinetic theory of gases can explain why a scent would arise as a

by-product of cooking soup. But we do not know of any neural

mechanism that can explain any of the more advanced capabilities of

the human mind. We know of no way in which neural activity can

produce spirituality, artistic creativity, mathematical reasoning

ability, insight, curiosity, philosophical reasoning ability, either

directly or as a by-product of anything else. So we don't have any

business claiming that such things are by-products of brain

activity.

- Something could only be explained as a

by-product of some survival-related skill if there is a close

similarity between the two. For example, we might plausibly say that

humans accidentally can throw baseballs accurately because such a

skill is a kind of a by-product of the ability to throw rocks

accurately, something cave-men needed to defend themselves from

animal attacks and do certain types of hunting. But there is not the

slightest relationship or similarity between things such as hunting

skills or cave survival skills and philosophical reasoning,

spirituality, linguistic creativity and musical ability. So things

such as philosophical reasoning, spirituality, linguistic creativity

and musical ability cannot be plausibly explained as by-products of

something else humans needed for survival.

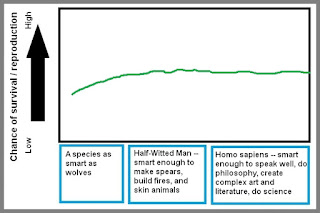

Let's imagine some species that was rather like man but much less intelligent and with a much smaller brain. We can call this species Half-Witted Man. Let's imagine that Half-Witted Man was smart enough to build spears, make fires, and skin animals, but not smart enough to make art, make complex inventions, speak grammatically, create music, and think philosophical thoughts. Half-Witted Man would have been just as likely to survive as Homo sapiens. A band of Half-Witted Men would have done just fine in the wild, just as packs of wolves do fine in the wild. Any small additional survival value that Homo sapiens got from its greater intelligence would have been canceled out by the fact that maternal childbirth deaths and stillborn deaths are much more common for organisms with bigger brains, as bigger heads are harder to fit through a vaginal birth canal.

So there's no evolutionary or natural selection reason why there would have been a progression from Half-Witted Man to Homo sapiens. Our higher mental abilities cannot be explained as spandrels or by-products of some mental brilliance that man acquired, because there was no evolutionary or natural selection reason why such mental brilliance would have appeared. You don't need to be an Einstein to be a hunter in a pack of hunters; you only need to be as smart as a wolf.

The diagram below illustrates the point.

If it were true that most characteristics and abilities of the human mind were things that increased the survival value of primitive humans, this would not at all mean that we had any explanation for the appearance of such characteristics and abilities. This is because no complex innovations can ever be explained by natural selection. Because natural selection can only occur in regard to some characteristic after that characteristic has appeared, we never explain any complex innovation by appealing to natural selection. What kind of situation do we have when most mental characteristics and abilities of humans do not even increase survival value or reproduction likelihood, and thinkers like Miller must say that all such things are mere spandrels or by-products? We have a situation in which it is particularly clear that there is no merit in the pretentious claims of such persons to have explanations for our mental capabilities.

On page 136-137 Miller says this about the evolution of the human brain:

In the jumble of growth and reorganization, new connections were forged that cut through the old structures. It is these connections, these new links, that account for the depth of consciousness and thought that distinguish us from other primates.

But, to the contrary, neither brain cells nor connections between brain cells do anything to account for any of the higher mental aspects or mental capabilities of humans. Thoughts and consciousness are mental things and neurons are physical things. We should not expect thought or spirituality or philosophical reasoning or abstract ideas to be produced by a billion neurons that each had 1000 connections to other neurons; and we should not expect any such mental phenomena to arise even if there were a billion trillion neurons that each had a billion trillion quadrillion connections to other neurons. If any of us think that “connected brain cells” somehow yields a mental ability, it is purely because we have been conditioned to think such a silly idea. If we had always had some very different type of body, or had always lived as creatures of pure energy or pure spirit, we might think such an idea as no more credible than the idea that a bunch of trees all connected by roots can give rise to advanced thinking.

On page 135 to 137 Miller suggests that “spandrels” can explain the origin of language, noting that this view is “enormously controversial” among linguists and anthropologists. His thinking again is along the lines of: we got bigger brains to hunt better and survive better in the wild, and then we got all this stuff like language as incidental by-products of bigger brains. Trying to explain the origin of language in such a way is particularly implausible, because the origin of language requires three things that are much more than just higher thinking abilities. For one thing, you must explain the establishment of the language itself (its vocabulary and grammar rules), which is pretty much impossible given that you would need to have a language first in order to establish a language among a large group of people, so that all such people started using the same grammar rules and the same vocabulary. Secondly, spoken language requires many language-specific features of the human larynx, pharynx and vocal tract, and such things would not at all appear as incidental by-products of a larger brain. Third, spoken language requires a great deal of specialization in the brain for making the very subtle muscle movements needed for spoken speech. So if an organism merely becomes as intelligent as a human, it would still lack three things it needed for speech. So we cannot at all explain the origin of language merely by saying it was a by-product or spandrel of man's higher intellect.

Miller quotes approvingly on page 141 an argument for the claim that the brain is like a computer. The argument he quotes goes like this: humans can surely compute, because you can add numbers, so the brain must be like a computer. This argument is entirely fallacious, for while we know that humans can add numbers, we do not at all know that brains are doing such a thing. All higher thought could be product of a human soul rather than the human brain.

On page 146 Miller engages in the typical sophistry of people trying to leverage the notion of emergent properties. Such thinkers often remind us that some properties can suddenly emerge. For example, if we freeze liquid water, then we suddenly have the property of hardness that we didn't have before. So, such reasoners say, maybe we can explain life and human mentality as emergent properties. Miller states the following:

Life, as we have come to understand it, is a collective property of many atoms and molecules. In very much the same way, thought is the collective property of millions, no, of billions of neurons.

Such reasoning is fallacious. A property is a single simple characteristic of something that can be expressed as a single number. Width, depth, height, mass and hardness are all legitimate examples of properties (the hardness of an object is measured on the numerical Mohs scale). But neither life nor thought are properties. Underestimating its complexity, we can say life is an incredibly complicated state of organization. That is not a single simple characteristic that can be expressed by a number. As for thought, it also is not a simple characteristic, cannot be expressed by a number, and is not a property.

The reasoning quoted above is also inconsistent with what Miller states on page 168, where he states that “consciousness, similarly, is not a property of matter” but is instead a process, thereby contradicting his claim on page 146 that “thought is the collective property of millions, no, of billions of neurons.”

No comments:

Post a Comment