Fatal Difficulty #1: No Explanation for Why Any Useless Early Stage Would Appear in a Population of Organisms

In general Darwinism fails to explain the first stages of useful structures. This was pointed out very clearly in Darwin's time by the biologist Mivart, who wrote the following at the beginning of Chapter II of his book On the Genesis of Species: "Natural Selection utterly fails to account for the conservation and development of the minute and rudimentary beginnings, the slight and infinitesimal commencements of structures, however useful those structures may later become." Mivart devoted Chapter II of that book to many examples of "incipient stages" that Darwinism could not explain well, including the first small part of any limb such as an arm or leg or the first small part of a wing or the first small part of a mammary gland.

Darwinists have told many a tall tale to try to account for such things, such as suggesting that maybe wings grew out of wing stumps that were used to catch insects. Such tales are typically unbelievable. Two of the attempts that Darwin made to suggest such stories are now believed to be erroneous (biologists now reject his "maybe mammals come from marsupials" explanation for the incipient stages of mammary glands, and also reject his "lungs come from swim bladders" explanation for the incipient stages of lungs).

Darwinists have told many a tall tale to try to account for such things, such as suggesting that maybe wings grew out of wing stumps that were used to catch insects. Such tales are typically unbelievable. Two of the attempts that Darwin made to suggest such stories are now believed to be erroneous (biologists now reject his "maybe mammals come from marsupials" explanation for the incipient stages of mammary glands, and also reject his "lungs come from swim bladders" explanation for the incipient stages of lungs).

Consider the case of the biological implementation needed to produce vision. We can call this a vision system, and it requires much more than just an eye. Below are four requirements of a vision system.

- Some type of eye.

- An optic nerve leading from the eye to the brain.

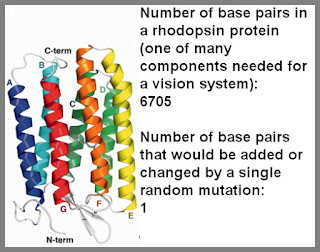

- Extremely complicated proteins used to capture light, such as rhodopsin.

- Very complex brain changes needed to allow for a vision effect that is useful for an organism.

Now if an organism had only or two of these things, it would receive no benefit. For example, merely having an eye and an optic nerve would not be useful unless the eye had the protein molecules needed for vision, and unless the eye also connected to changes in a brain needed to make use of visual inputs. And if there were only such proteins and such brain changes, and no eye and no optic nerve, that would not be beneficial.

The general principle that the first stages of an implementation are not beneficial can be stated as the principle of preliminary implementations. We can state this principle like this:

The principle of preliminary implementations: in almost all cases, with few exceptions, preliminary or fragmentary implementations of very complex organized things by themselves yield no benefits or rewards.

This principle holds true in general life (as the examples above show), and also in regard to biological implementations. So if we are speaking of some complex biological innovation requiring a certain number of parts organized in the right way, we should not at all assume that the first stages of such an innovation will provide a benefit. A benefit will occur only when a certain degree of complexity and functional coherence has been achieved. In other words, no benefit will come unless some functional threshold has been reached. Such a functional threshold will typically require that several or many parts are arranged in the right way. The diagram below illustrates the point.

The reason why Darwin's ideas do not work to credibly explain the origin of biological innovations was rather well explained by scientist Gustave Geley in his monumental work From the Unconscious to the Conscious. He mentioned "embryonic organs" that are "merely adumbrated" to refer to some mere useless preliminary fragment of an organ. He stated the following:

"It is not difficult to show that neither the Darwinian

nor the Lamarckian hypothesis enables us to understand

the origin of characteristics that constitute a new

species...In order that any given modification occurring in

the characteristics of a species or an individual, should

give to that species or to that individual an appreciable

advantage in the struggle for life, it is evident that this

modification must be sufficiently marked to be utilizable.

Now an embryonic organ, a modification merely

adumbrated, appearing by chance in a being or a group

of beings, can be of no practical use and give them no

advantage....Now an embryonic

wing, appearing by chance, one knows neither how nor

why, in the ancestral reptile, could not give that reptile

the capacity or the advantage of flight, and would give

it no superiority over other reptiles unprovided with the

unusable rudiment. It is therefore impossible to attribute

to natural selection the transition from reptile to bird.

...Rudiments of legs and lungs would give no

advantage to a fish...It is indispensable that its heart, lungs, and organs of locomotion should be already sufficiently developed to allow it to live out of the water."

We can imagine some useless early stage of a useful innovation appearing in a single member of a species because of some random variation. But because such a useless early stage would provide no survival value, it would not spread around from a single organism to reach most members of a species in subsequent generations in a "selective sweep" occurring because of "survival of the fittest" reasons.

In fact, useless early stages would often be not just useless but actually detrimental to the survival chances of an organism. An example would be a not-yet functional appendage that was the beginning of a wing. Such an appendage would slow down an organism that had it, and make an easy target for predators to bite. Another example would be a rudimentary not-yet-functional eye lens, which would tend to block light and reduce sight until it became a sophisticated functional lens.

Darwin attempted to answer the problem of useless early stages by speculating on some examples of useful early stages. But far from being answered by his speculations, the problem of useless early stages has grown gigantically larger after Darwin because of what we have discovered about the great complexity and fragility of protein molecules, something Darwin never knew about. We now know that the animal kingdom contains millions of different types of protein molecules, each its own separate complex invention, typically with hundreds of amino acids that have to be arranged in just the right way for the molecule to be functional. In the human body there are roughly 20,000 different types of protein molecules, each its own separate complex invention. Experiments have repeatedly shown that protein molecules are fragile, and become nonfunctional when only a small fraction of their amino acids are removed. A biology textbook tells us, "Proteins are so precisely built that the change of even a few atoms in one amino acid can sometimes disrupt the structure of the whole molecule so severely that all function is lost." And we read on a science site, "Folded proteins are actually fragile structures, which can easily denature, or unfold." Another science site tells us, "Proteins are fragile molecules that are remarkably sensitive to changes in structure." Protein molecules are not functional if only a half or a third of their amino acids exist. Typically we have no credible explanation for why the first half or the first third of any protein molecule would have ever originated. So what we have learned about protein molecules causes the problem of useless early stages to loom a hundred times larger than it did in Darwin's time.

Besides protein molecules that are not useful when only half of the molecule exists, there are countless larger features of organisms that are not useful when only half of such features exist. Some of these features are mentioned by biologist , Richard Goldschmidt, who wrote the following on page 6 of his book The Material Basis of Evolution:

"I may challenge the adherents of the strictly Darwinian view, which we are discussing here, to try to explain the evolution of the following features by accumulation and selection of small mutants: hair in mammals, feathers in birds, segmentation of arthropods and vertebrates, the transformation of gill arches in phylogeny, including the aortic arches, muscles, nerves, etc.; further, teeth, shells of mollusks, ectoskeletons, compound eyes, blood circulation, alternation of generations, statocysts, ambulacral system of echinoderms, pedicellaria of the same, cnidocysts, poison apparatus of snakes, whalebone, and, finally, primary chemical differences like hemoglobin vs. hemocyanin, etc. Corresponding examples from plants could be given.”

The diagram below illustrates how a protein molecule can be made nonfunctional by a very small mutation involving a change in only one or a few of the protein's amino acids. The lack of a credible natural explanation for the origin of protein molecules becomes all the more apparent when we ponder the need for most types of protein molecules to have very special sequences of hundreds or thousands of amino acids that have to be almost exactly right for the molecule to function.

Below are some relevant statements by scientists:

- "It seems clear that even the smallest change in the sequence of amino acids of proteins usually has a deleterious effect on the physiology and metabolism of organisms." -- Evolutionary biologist Richard Lewontin, "The triple helix : gene, organism, and environment," page 123.

- "Proteins are so precisely built that the change of even a few atoms in one amino acid can sometimes disrupt the structure of the whole molecule so severely that all function is lost." -- Science textbook "Molecular Biology of the Cell."

Fatal Difficulty #2: The Great Rarity or Nonexistence of Nonfunctional Adult Features That Are Merely the Initial Stages of Biological Innovations

If you do a Google search for "incipient organ" or "nascent organ" or "incipient appendage," you will get many matches. But the search results matches will be talking about incipient organs and incipient appendages that arise during morphogenesis and embryonic development, long before an organism reaches adulthood. The matches will not be discussing nonfunctional adult features that are merely the initial stages of biological innovations that may occur later in the evolution of a species.

If it were true that gradual random changes led to very complex visible biological innovations, then we would see all over the place (in the animal world) adult organisms with not-yet-functional biological innovations existing in rudimentary form: what can be called incipient organs, nascent organs, incipient appendages or nascent appendages. But we see no such thing. We do not see any adult organisms containing not-yet-functioning organs that are the initial stages of organs that will be functional in future generations. We do not see any adult organisms with not-yet-functioning appendages that are merely the initial stages of appendages that will only be functional in future generations. Inside the bodies of organisms we see no protein molecules that are presently useless but which are the first half or the first third of some molecule that will be highly functional in future generations.

If it were true that gradual random changes led to very complex visible biological innovations, then we would see all over the place (in the animal world) adult organisms with not-yet-functional biological innovations existing in rudimentary form: what can be called incipient organs, nascent organs, incipient appendages or nascent appendages. But we see no such thing. We do not see any adult organisms containing not-yet-functioning organs that are the initial stages of organs that will be functional in future generations. We do not see any adult organisms with not-yet-functioning appendages that are merely the initial stages of appendages that will only be functional in future generations. Inside the bodies of organisms we see no protein molecules that are presently useless but which are the first half or the first third of some molecule that will be highly functional in future generations.

The point that I make here was forcibly made in pages 24-26 of Douglas Dewar's book Difficulties of the Evolution Theory. Dewar states this:

"Better evidence of the assertion that for the last fifty years biological textbooks bring to light only that which is favourable to evolution and pass over unnoticed all that is unfavourable could scarcely be adduced than the fact that these volumes contain many references to vestigial organs, but none to nascent organs....Thus, although the anatomy of thousands of species of animals has been carefully studied, it is impossible to adduce a single structure in any species which is indubitably or even probably in a nascent condition."

Fatal Difficulty #3: Nonfunctional Intermediates

It is typically true that we cannot imagine a transition between two very different and highly-functional biological things without a passage through an intermediate state that is nonfunctional. For example, if over very many thousands or millions of years one specialized protein molecule changed gradually to become some other specialized protein molecule with a different function, there would have been an intermediate non-functional state; but in such a state such a molecule would have tended to have fallen out of a gene pool, preventing the imagined transition.

Let us consider an elementary example of nonfunctional intermediates during a transition from one functional thing to another. Suppose I have a red "stop" sign, and I wish to modify this to serve another function: the function of being a "tow zone" sign. I can do this in three steps:

(1) I use red paint to cover the "s" and the "p" in "stop."

(2) Painting where the "p" was in "stop," I paint a "w."

(3) I then paint "zone" under what was originally the word "stop."

Now I have changed my functional "stop" sign to be a functional sign saying "tow zone." The visual below illustrates the steps:

Yes, a functional stop sign can be gradually changed into a functional "tow zone" sign. But if you do this, you will have to pass through two stages that are nonfunctional. Both stages 2 and 3 shown above are nonfunctional intermediates. If we get a nonfunctional intermediate when doing such a simple transition, we should suspect that nonfunctional intermediates would occur all over the place in a gradual transition between two complex biological units such as protein molecules.

Let's imagine another gradual transition, this time using something more complex. Let's imagine you were to try to gradually change an automobile so that it became a functional boat. You could do this through the following steps.

(1) Open the car's hood and yank out everything connected to the engine block.

(2) Then remove the entire engine block.

(3) Remove the car's wheels and axles.

(4) Remove the car's steering wheel.

(5) Remove the car's exhaust system.

(6) Remove the car's two front seats

You would now have a car so light that it might well float if tossed into the ocean. So it's quite possible that an automobile could be gradually changed to become a crude boat. But the problem is that in the middle of such a transition there would be nonfunctional intermediates. At some point during this transition, we would have something that was neither a functional car, nor something light enough to be a functioning boat.

There would be nonfunctional intermediates all over the place during the type of gradual biological transitions imagined by proponents of gradualism. The problem with that is according to Darwinist theory, when a nonfunctional state is reached, then evolution should discard something. As Darwin put it, "Natural selection is daily and hourly scrutinizing, throughout the world, the slightest variations; rejecting those that are bad, preserving and adding up all that are good." So the imagined Darwinian process of so-called natural selection can never pass through nonfunctional intermediates while on some long process of producing a functional result. It can only produce some final good result by some long sequence such as this:

Fatal Difficulty #3: Nonfunctional Intermediates

It is typically true that we cannot imagine a transition between two very different and highly-functional biological things without a passage through an intermediate state that is nonfunctional. For example, if over very many thousands or millions of years one specialized protein molecule changed gradually to become some other specialized protein molecule with a different function, there would have been an intermediate non-functional state; but in such a state such a molecule would have tended to have fallen out of a gene pool, preventing the imagined transition.

Let us consider an elementary example of nonfunctional intermediates during a transition from one functional thing to another. Suppose I have a red "stop" sign, and I wish to modify this to serve another function: the function of being a "tow zone" sign. I can do this in three steps:

(1) I use red paint to cover the "s" and the "p" in "stop."

(2) Painting where the "p" was in "stop," I paint a "w."

(3) I then paint "zone" under what was originally the word "stop."

Now I have changed my functional "stop" sign to be a functional sign saying "tow zone." The visual below illustrates the steps:

Let's imagine another gradual transition, this time using something more complex. Let's imagine you were to try to gradually change an automobile so that it became a functional boat. You could do this through the following steps.

(1) Open the car's hood and yank out everything connected to the engine block.

(2) Then remove the entire engine block.

(3) Remove the car's wheels and axles.

(4) Remove the car's steering wheel.

(5) Remove the car's exhaust system.

(6) Remove the car's two front seats

You would now have a car so light that it might well float if tossed into the ocean. So it's quite possible that an automobile could be gradually changed to become a crude boat. But the problem is that in the middle of such a transition there would be nonfunctional intermediates. At some point during this transition, we would have something that was neither a functional car, nor something light enough to be a functioning boat.

There would be nonfunctional intermediates all over the place during the type of gradual biological transitions imagined by proponents of gradualism. The problem with that is according to Darwinist theory, when a nonfunctional state is reached, then evolution should discard something. As Darwin put it, "Natural selection is daily and hourly scrutinizing, throughout the world, the slightest variations; rejecting those that are bad, preserving and adding up all that are good." So the imagined Darwinian process of so-called natural selection can never pass through nonfunctional intermediates while on some long process of producing a functional result. It can only produce some final good result by some long sequence such as this:

- Good result.

- Some later result that is also good.

- Some still later result that is also good.

- Final good result.

It can never produce some final good result by some long process such as this:

- Good result.

- Some later result that is also good.

- Some later nonfunctional result that does no good.

- Final good result.

Fatal Difficulty #4: Anatomically Uninformative DNA

Perhaps the greatest problem with gradualism arises from the lack of any such thing as a specification for making an organism in the body of that organism. If we knew that there was such a thing as a specification for making an organism somewhere in the organism, we might imagine that such a specification had gradually changed over vast lengths of time. But inside an organism there is no such specification for making an organism. The DNA in an organism merely specifies low-level chemical information such as how to make the polypeptide chains that are the beginning of protein molecules. DNA does not specify how to build the overall structure of an organism, nor does it specify how to make any organ of an organism, nor does it even specify how to make any of the cells of an organism. Humans have about 200 different cell types, and DNA does not specify how to make any of those types of cells. Containing no information about anatomy or how to construct the cells or bodies of organisms, DNA is correctly described as anatomically uninformative.

So we cannot at all credibly imagine that over a huge length of time one species gradually changed into some other very different species with a very different anatomy, because of random mutations that produced gradual changes in DNA. This is such a problem for gradualism that biologists have repeatedly tried to cover up the problem by telling us the lie that DNA is a blueprint or recipe for making an organism. When the proponents of an idea have to resort to telling us an outrageous lie to try and cover up problems with their theory, this should be a very big warning sign that something is very, very wrong with their thinking.

Perhaps the greatest problem with gradualism arises from the lack of any such thing as a specification for making an organism in the body of that organism. If we knew that there was such a thing as a specification for making an organism somewhere in the organism, we might imagine that such a specification had gradually changed over vast lengths of time. But inside an organism there is no such specification for making an organism. The DNA in an organism merely specifies low-level chemical information such as how to make the polypeptide chains that are the beginning of protein molecules. DNA does not specify how to build the overall structure of an organism, nor does it specify how to make any organ of an organism, nor does it even specify how to make any of the cells of an organism. Humans have about 200 different cell types, and DNA does not specify how to make any of those types of cells. Containing no information about anatomy or how to construct the cells or bodies of organisms, DNA is correctly described as anatomically uninformative.

So we cannot at all credibly imagine that over a huge length of time one species gradually changed into some other very different species with a very different anatomy, because of random mutations that produced gradual changes in DNA. This is such a problem for gradualism that biologists have repeatedly tried to cover up the problem by telling us the lie that DNA is a blueprint or recipe for making an organism. When the proponents of an idea have to resort to telling us an outrageous lie to try and cover up problems with their theory, this should be a very big warning sign that something is very, very wrong with their thinking.

Read the end of this post for quotes by more than twenty distinguished biology authorities very clearly stating that DNA is not a recipe or blueprint or program for making an organism or a human. For example, on the web site of the well-known biologist Denis Noble, we read that "the whole idea that genes contain the recipe or the program of life is absurd, according to Noble," and that we should understand DNA "not so much as a recipe or a program, but rather as a database that is used by the tissues and organs in order to make the proteins which they need." At the same link we read statements by Sergio Pistoi (a science writer with a PhD in molecular biology) who tells us, "DNA is not a blueprint," and tells us, "We do not inherit specific instructions on how to build a cell or an organ"; and we read the director of a biology research lab tell us that "genomes are not a blueprint for anatomy." "The genome is not a blueprint," says Kevin Mitchell, a geneticist and neuroscientist at Trinity College Dublin. "It doesn't encode some specific outcome." His statement was reiterated by another scientist. "DNA cannot be seen as the 'blueprint' for life," says Antony Jose, associate professor of cell biology and molecular genetics at the University of Maryland. He says, "It is at best an overlapping and potentially scrambled list of ingredients that is used differently by different cells at different times."

Even if there existed a blueprint in DNA for making an organism, that would not explain the origin of adult bodies, for the elementary reason that blueprints don't build things. Buildings get built because there are intelligent construction workers who read blueprints and carry out their instructions. If there were to exist in DNA fantastically complicated instructions for building a human body with its gigantically complex hierarchical organization (which would have to be instructions more complex than any humans have ever written), we know of nothing in the human body (below the neck) capable of acting on and carrying out such instructions if they happened to exist. The idea that adult human bodies arise because of a reading of a DNA blueprint is therefore one that is false and very childish, as silly as the idea that a balloon could take you to the moon. A child imagining that a balloon can rise to the moon fails to consider the elementary "show-stopper" fact that a balloon would stop rising once it reached the vacuum of space. A gradualist imagining that adult bodies arise because of a reading of DNA blueprints fails to consider the elementary "show-stopper" facts that DNA has no blueprint for building a body and that blueprints don't build things.

So how is it that an adult human body (with its many levels of hierarchical organization) arises from the billion-times-simpler state of a speck-sized egg existing just after conception? Our biologists do not understand this great mystery of progression, which is a thousand miles over their heads. An article in the journal Nature states this: "The manner in which bodies and tissues take form remains 'one of the most important, and still poorly understood, questions of our time', says developmental biologist Amy Shyer, who studies morphogenesis at the Rockefeller University in New York City." No one lacking an explanation for this great mystery has any business claiming he understands the origin of humanity; for if you do not understand the origin of even a single adult body, what business do you have claiming that you understand the origin of the whole human race? That would be like claiming that you understand the origin of cities when you don't even understand the origin of buildings. When we consider that our biologists also lack a credible account for the origin of individual adult minds, their boasts about understanding human origins seem all the more hollow.

Gradualism (the idea that every species appeared because of very many tiny random changes that gradually took place over long periods of time) does not work as a credible explanation for the origin of species. To credibly explain in some natural manner organisms that have incredibly high levels of organization all over the place, what you would need (at the very least) is some theory credibly explaining why there occurred so often vastly impressive feats of purposeful biological organization. Gradualism is no such thing.

Gradualists frequently commit in their thinking a common logic error that is known as the fallacy of composition. The fallacy of composition is the fallacy of assuming that each part in a whole must have some property that the whole possesses. An example of this fallacy is found is this statement: "A big bag of sand is heavy, so each of its parts must be heavy." No, that's wrong. The parts of a big bag of sand are millions of grains of sand, and a bag; and none of those things is heavy.

There are millions of different types of functional protein molecules in the animal kingdom, each its own separate very complex invention. The human body contains more than 20,000 types of protein molecules, each a very complex invention. The median number of amino acids in a human protein molecule is about 375.

Pondering some thing such as a protein molecule (consisting of hundreds of amino acids arranged in just the right to achieve a functional result), our gradualism believer assumes that each of hundreds of mutations that might have combined to produce the useful molecule would produce a benefit. That is the fallacy of composition. Typically the property of being beneficial in the protein molecule only arises "late in the game" when hundreds of the amino acids appeared and were organized in just the right way to produce a functional protein molecule, something that would be as unlikely to occur by chance as typing monkeys producing a useful paragraph of hundreds of characters. It is absolutely fallacious to assume that each little mutation would itself be beneficial, as fallacious as thinking that each of the hundreds of pixels that make up a functional sentence produces a benefit because the sentence produces a benefit.

No comments:

Post a Comment