For

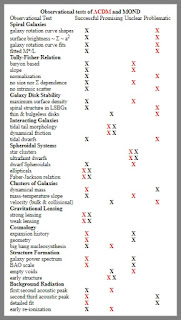

reasons I discussed in my previous post and also in this longer post, the evidence is overwhelming

that a specification for the human body plan does not exist in DNA.

But some scientists continue to push the myth that DNA is a

specification of the human body plan. An example of a scientist doing

such a thing is a recent book entitled How to Code a Human: Exploring

the DNA Blueprints That Make Us Who We Are by biologist Kat Arney.

Arney's wavering claims about DNA flip-flop all over the map, and we

can frequently find one claim she makes on this matter that

contradicts other claims she makes on this matter.

Let

us look at the wildly inconsistent claims that Arney makes about DNA.

Claim

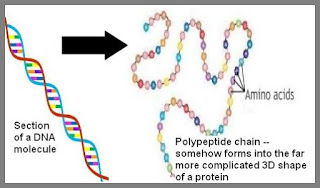

#1: DNA simply has recipes for making molecules. This relatively

modest claim is made on page 9 of Arney's book, where she says,

“Genes are recipes for making molecules.” The same claim of genes

as recipes is made on pages 34 to 35. Even this relatively modest

claim is not correct, because DNA merely specifies an ingredient list

for molecules such as protein molecules. DNA does not specify the

three-dimensional shapes that such molecules need to have in order to

be useful.

Claim

#2: DNA consists of genes that are “living entities.” On page 8

of her book Arney says this:

Instead

of being like computer code, with tidy electrical circuits, genes are

more like recipes. They are living entities, full of constantly

shifting molecules and with many options for flexibility, depending

on the range of things a cell needs to manufacture.

In

this statement, we have multiple glitches. First, computer code does

not contain electrical circuits. Second, genes (particular sections

of DNA) are chemical units (fractions of a molecule) that are not

living entities. Third, you contradict yourself very obviously if

you first say that a gene is a recipe (a lifeless, inert thing), and

then in your next sentence claim that a gene is a living entity.

Fourth, a gene is part of a DNA molecule, not something “full of

constantly shifting molecules.”

Below

is an example of a recipe, and it includes both an ingredient list

and assembly instructions. Neither DNA nor the genes in it are

recipes, for they do not contain any assembly instructions.

Nowhere in DNA or one of its genes is there anything like an assembly

instruction for making a cell, a tissue, an organ, an organ system,

an appendage such as an arm, or a full organism. DNA is written in a

bare-bones “amino acid language” that is so lacking in expressive

capability that it is impossible that DNA could ever even have assembly

instructions for a simple cell, a unit of such complexity that it is often compared to a small city.

Recipes include assembly instructions

Claim

#3: DNA is like computer code, and “directs the processes of life.”

The title of Arney's book about DNA is “How to Code a Human.” The title implies that DNA is like some

computer software that specifies the functionality of how human

biology works. Also on page 6 Arney tells us that “the genetic

information encoded in our DNA directs the processes of life.” But such a

claim is inaccurate. Since DNA has only one-dimensional information

specifying chemical ingredients, it could not possibly be something

that “directs the processes of life.” And claims about DNA being

like computer code that “directs the processes of life” are inconsistent with Arney's claim on page 8 that “instead of being

like computer code” genes are “more like recipes.” Recipes

don't direct things.

Claim

#4: DNA is some kind of agent that directs embryonic development.

This claim is made on page 116 where Arney claims that genes “direct

embryonic development” and that “genetic rules and patterns" guide embryonic development. These claims are contradicted by her

confession on page 7 that “scientists are only just beginning to find

the answers to some really big questions such as: how does a

fertilized egg divide and specialize to make all the tissues of the

body?” When a scientist says that his colleagues are “only just beginning to find the answers” to some matter, it essentially means

they don't understand the matter and know almost nothing about it. So

how then can Arney possibly be claiming that genes “direct

embryonic development”?

Arney

provides no evidence to back up her claim that genes “direct

embryonic development,” other than mentioning the feeble evidence

of Hox genes, the role of which is murky. Having failed to back up

this claim, she resorts on page 125 to saying, “There is not enough

space in this book to go into the details of human development and

the genes that direct it.” We may be forgiven for concluding that

the real reason she is not listing any solid evidence for the claim

that genes direct embryonic development is that such evidence does

not exist and cannot possibly exist (given the expressive limits of

DNA), not that there was not enough space in her book.

Claim

#5: DNA consists of blueprints. This claim is made in the subtitle of

Arney's book, which is “Exploring the DNA Blueprints That Make Us

Who We Are.” The claim the DNA consists of blueprints is

inconsistent with Arney's previous claim that DNA consists of recipes.

A blueprint is a specification of the three-dimensional layout of

something, and according to the usual understanding of a blueprint, a

blueprint does not include assembly instructions. In this sense it is

the opposite of a recipe, which does include assembly instructions,

but does not specify the exact physical layout of the final product.

The claim that DNA consists of blueprints is also inconsistent with

Arney's previous claims that genes “direct the processes of life”

and “direct embryonic development.” Blueprints are passive things

that don't direct anything. A blueprint is not an agent.

As

for claim #4 and claim #5, they are both explicitly debunked by

Agustin Fuentes, a professor of anthropology, who states the

following:

Genes

play an important role in our development and functioning, not as

directors but as parts of a complex system. “Blueprints” is a

poor way to describe genes. It is misleading to talk about genes as

doing things by themselves.

In

statements such as this, scientists "fess up" that the idea

of DNA as a human specification is not true. Two other scientists

"fess up" in a similar way when they write the following about genes in

the journal Nature: "Population

genetics is founded on a subset of coding sequences that can be

related to phenotype in a statistical sense, but not based on

causation or a viable causal mechanism."

Regarding

the DNA as blueprint idea (claim #5), a wikipedia.org article

entitled “Common misunderstanding of genetics” lists the claim

that “Genes are a blueprint of an organism's form and behavior”

as one of the “common misunderstandings of genetics.”

These five claims by Arney are wildly inconsistent, and all over the map. DNA

cannot be an agent and a director if it merely consists of

blueprints; and if it consists of blueprints, it cannot consist of

recipes; and if genes are blueprints, they cannot be like computer

code, which works totally different from a blueprint. When you hear

someone throwing out such a variety of claims that conflict with each

other, you should suspect that their claims lack a foundation in

fact. And that is the case here.

In

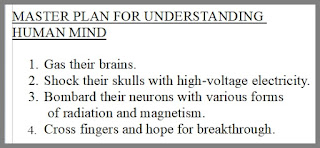

its article on “molecular genetics,” the Stanford Encyclopedia of

Philosophy says the following:

The

fundamental theory that says the role of DNA is to provide the

information for development has been criticized on many

grounds....Philosophers have generally criticized the theory that

genes and DNA provide all the information and have challenged the use

of sweeping metaphors such as “master plan” and “program”

which suggest that genes and DNA contain all developmental

information....It is not clear that they can elucidate the idea that

genes are "fundamental" entities that "program"

the development and functioning of organisms by "directing"

the syntheses of proteins that in turn regulate all the important

cellular processes. In fact, there is considerable skepticism in the

philosophical community about this fundamental theory.

Another

relevant article in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy is its

article on developmental biology. That article tells us that there

is no theory explaining how the development of an organism occurs.

We read the following:

It

is uncommon to find presentations of developmental biology that make

reference to a theory of development. Instead, we find references to

families of approaches (developmental genetics, experimental

embryology, cell biology, and molecular biology) or catalogues of

“key molecular components” (transcription factor families,

inducing factor families, cytoskeleton or cell adhesion molecules,

and extracellular matrix components). No standard theory or group of

models provides theoretical scaffolding in the major textbooks (e.g.,

Slack 2013; Wolpert et al. 2010; Gilbert 2010). The absence of any

reference to a theory of development or some set of core explanatory

models is prima facie puzzling. Why is it so difficult to identify a

constitutive theory for developmental biology?

These

assertions contradict Arney's claim that genes “direct embryonic

development.” Evidently such a theory has not become very

widespread, for the quote above makes clear that there is simply no general theory of what causes embryonic development.

Arney

contradicts herself all over the place when talking about DNA and

genes. A similar lack of consistency on this topic is found in an

Aeon essay by biologist Itai Yanai. Below is a quote:

At

the most fundamental level, then, our genome is not a blueprint for

making humans at all. Instead, it is a set of genes that seek to

replicate themselves, making and using humans as their agents. Our

genome does of course contain a human blueprint – but building us

is just one of the things our genome does, just one of the strategies

used by the genes to stay alive.

The

biggest problem here is not the anthropomorphic nonsense about genes seeking things and “using humans

as their agents,” but the glaring contradiction of saying in one

sentence “our genome is not a blueprint for making humans at all,”

and then saying two sentences later, ”Our genome does of course

contain a human blueprint.” That's

another case of a scientist saying something false, and adding an “of

course” to compound the error. See this post for why

genes and DNA cannot be truthfully considered a blueprint for a

human being.

In

this post entitled “DNA is a recipe, NOT a blueprint,” a PhD

student in “molecular evolution” debunks the claim that DNA is a

blueprint, asserting emphatically, “Describing the genome as a

blueprint is a recipe for disaster.” But the author then asserts

the equally incorrect idea that DNA is a recipe, saying it “is

much more accurate” to describe DNA as “a recipe or set of

instructions for making the organism.” No, it no more accurate to

describe DNA as a recipe than to describe it as a blueprint, because

there is in DNA no “set of instructions for making the organism,”

no set of instructions for making an organ system, no set of

instructions for making an organ, no set of instructions for making a

tissue, no set of instructions of making a cell, and not even a lowly

set of instructions for making a single three-dimensional protein

molecule. DNA has merely the chemical ingredient lists of proteins.

Advancing

the Great DNA Myth that DNA is a human specification, our biologists

flip flop all over the map, contradicting each other, with a single

biologist often contradicting himself or herself on this topic.

Jonathan

Latham has a master's degree in Crop Genetics and a PhD in virology.

In his essay “Genetics Is Giving Way to a New Science of Life,” a

long essay well worth a read, Latham exposes many of the myths about

DNA. He states the following:

A

standard biology education casts DNA (DeoxyriboNucleic Acid) as the

master molecule of life, coordinating and controlling most, if not

all, living functions. This master molecule concept is popular. It is

plausible. It is taught in every university and high school. But it

is wrong. DNA is no master controller, nor is it even at the centre

of biology....Does DNA have any claim to being in control? Or even

just to be at the centre of biological organisation? The answer is

that DNA is none of the things Watson, Lander, and Collins claim

above, even the standard, supposedly nuanced, biologist’s view of

life is wrong...The evidence that DNA is not a biological controller

begins with the observation that biological organisms are complex

systems. Outside of biology, when we consider any complex system,

such as the climate, or computers, or the economy, we would not

normally ask whether one component has primacy over all the

others.....Geneticists, and sometimes other biologists, make this

linear interpretation seem plausible, not with experiments—since

their results contradict it—but by using highly active verbs in

their references to DNA. DNA, according to them, “controls”,

“governs”, and “regulates” cellular processes....However,

there is no specific science that demonstrates that DNA plays the

dominant role these words imply. Quite the opposite....It is

habitually, but lazily, presumed that DNA specifies all the

information necessary for the formation of a protein, but that is not

true....How is it that, if organisms are the principal objects of

biological study, and the standard explanation of their origin and

operation is so scientifically weak that it has to award DNA

imaginary superpowers of “expression” and “control” to paper

over the cracks, have scientists nevertheless clung to it?

It seems that just as many of our theoretical physicists have taken to indulging in what may be called Fantasy Physics, such as string theory and multiverse speculations, many of our biologists have been indulging in Fantasy Biology. One of the main aspects of Fantasy Biology is the claim that DNA is a human specification, something it cannot be because of its own inherent expressive limitations, which must prevent it from specifying anything a hundredth as complex as a human specification. Another of the main aspects of Fantasy Biology is the claim that human memories are stored in synapses, a claim that cannot be correct because memories can last 50 years, but the average lifetime of a synapse protein is less than a month, which means writing to a synapse would be as unsuitable for permanent storage as finger-writing in the wet sand at the edge of a seashore. In both cases, Fantasy Biology commits the sin of ignoring a physical limitation that should have constrained our thinking on a topic.