In

academic circles it is commonly assumed that consciousness is

generated by the brain. But many philosophers have been dissatisfied

with this idea. Why is it that some particular arrangement of matter

would cause Mind (a totally different type of thing) to emerge from

the matter in a brain? To many that seems no more plausible than the

idea that some particular arrangement of crystals in a rock might

cause the rock to gush out blood.

One

alternate idea is to assume that we have something like a soul, and

that our mental experiences are produced not mainly by matter (the

brain), but by something that is itself mental or spiritual. Another alternative

(called idealism or immaterialism) is to believe that everything is mental, and that

matter only exists as perceptions within minds. A third alternative is the idea that the brain doesn't actually produce our minds, but somehow taps into some great external reality that is the source of our minds, perhaps in a way rather similar to how a television set receives TV signals, or how a smartphone connects with the internet.

Yet another alternate idea is the radical notion known as panpsychism. Panpsychism has been described as the idea that consciousness is in everything.

Yet another alternate idea is the radical notion known as panpsychism. Panpsychism has been described as the idea that consciousness is in everything.

This

idea may not seem very unreasonable if we think of consciousness as

some very simple thing. But the word “consciousness” describes only

one aspect of human mentality, and there are many different aspects

of the human mind. The visual below reminds us of the many aspects of

mentality.

I doubt whether panpsychism theorists have thought out which of these aspects of mentality they think should be attributed to “all matter.” Below are some questions I would ask a panpsychist:

- How could dead matter be said to have consciousness or mind, when objects such as rocks, atoms and electrons do not have sensory organs? Do you maintain that such objects have some existence like some person born blind and deaf into the world, who also had some brain defect preventing a sense of touch?

- How would self-hood work under a scenario in which all matter is conscious? Is the Pacific ocean a single conscious self? Or is every drop of water its own conscious self? Or is there perhaps some particular unit of matter (such as a liter) which causes some quantity of water to achieve self-hood?

- Does each atom on a beach have its own self-hood, or does it take a grain of sand to make a sand self? Or does perhaps the whole beach constitute a single self?

- Do you maintain that lifeless objects have volition, the ability to will particular actions? If so, how do you reconcile such a belief with the complete lack of any evidence that lifeless matter is engaging in volition or willing actions?

- Do you maintain that lifeless objects have memories or thoughts? If you think they have either, how could that be, since thoughts require language (which could not be known by minds without sensory experience), and memories require either thoughts or sensations (which would seem to be impossible for a mind without sensory experience)?

- Do you maintain that lifeless objects have interests, pleasures, pains, attitudes, knowledge or ideas? How could lifeless objects have such things if they never had sensory experience?

Of

course, once we consider such questions we become entangled in a

great ocean of difficulties. Let us consider the question of

volition, which means the power to carry out some action. There are

two possibilities for a panpsychist. The first (call it option A) is

to maintain that lifeless objects can carry out actions by willing

them. One problem with this option is that lifeless objects do not

have sensory organs. So we can't really imagine any reasonable

scenario by which a lifeless natural object would will something to

occur. For example, if a lifeless asteroid were traveling through the

solar system, we cannot imagine it willing itself to move closer to

the Earth, because lacking all sensory organs, such a rock would

never know what Earth (or anything else) was.

Another

strong reason for rejecting option A is that there is zero evidence

that lifeless objects can will things. For example, on the subatomic

level, subatomic particles such as electrons and protons act with

unvarying precise obedience to the laws of electromagnetism. If they

did not, you would not be reading a coherent intelligible essay at

this moment, but would be seeing only a jumbled scramble of pixels. To give another example, astronomers find that things

such as asteroids and comets act with unvarying precise obedience to

the laws of gravity, showing no signs of independence.

So

it seems option A doesn't work. The alternative for a panpsychist

considering this question of volition in lifeless objects is what we

may call option B: the idea that lifeless objects with minds do not have any

power of volition. But when we think about this possibility, it

seems very depressing. Given their lack of sensory organs, lifeless

objects with a mind would be like a child born deaf, blind and

incapable of any tactile sensation. If we also imagine them having

no power of volition, we then imagine them like a child born

completely paralyzed, blind, deaf and incapable of feeling touch.

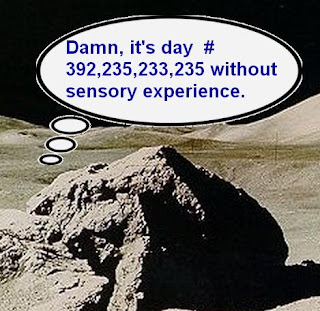

So

option B seems like quite a dismal scenario. If we have a universe filled with

1,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 conscious objects that are

like children born deaf, blind, paralyzed and without any sense of

smell, taste or touch, that is a dismal and repulsive scenario. The scenario becomes even more

dark and depressing when we ask ourselves: how long would these conscious but

lifeless objects live? The answer would apparently be: in many

cases, for billions of years. So, for example, if you were a

conscious rock on the moon, you would have to hang around for

billions of years in such an undesirable state: blind, deaf, and

paralyzed, unable to communicate with your fellow rocks, unable to do

anything. The panpsychist apparently must believe that for every

conscious human such as yourself who can exercise volition and enjoy

sensory experience, there are 1,000,000,000,000,000 or more conscious

entities living a horrid life of blindness, deafness and paralysis.

You might avoid such problems by believing that consciousness is in all matter, but that such consciousness consists of a single cosmic mind self. But that version of panpsychism would seem to do nothing to help explain how humans have minds. If your brain is merely a millionth of a billionth or a trillionth of .000000000000000000000000000000000000001 percent of the matter that gives rise to some single cosmic mind, that would not at all seem to imply that you should have a mind because of that tiny fraction.

A writer named Daniel Podgorski recently wrote a post entitled "A Scientific Defense of Panpsychism." The subtitle of his post was "Understanding Panpsychism through Evolutionary Biology and an Analogy to Electricity." He states the following:

Yet only extremely recently, in the 1800s, did the science of electromagnetism (born in that century from the distinct studies of electricity and magnetism) advance far enough to allow for the explosion of inventions whereby electricity has been harnessed to run a staggering proportion of the tools with which we live, work, and play daily. Electricity was already out there in the world, existing and happening. But only within certain arrangements of matter can electricity do things which are interesting and useful to human beings. My take on panpsychism is that consciousness is similar. It is out there in the world everywhere and it always has been, but only in certain arrangements of matter does it seem to really do anything.

There are several reasons why this analogy is fallacious:

(1) Electricity is something required by complex electrical machines, but it does not at all by itself give rise to the useful work they do. When electrical machines do things, it is incorrect to describe this as electricity doing things. Volts don't take me from Queens to Manhattan; a subway does.

(2) Electrical machines are designed products, but an evolutionary biologist does not believe that a brain is a designed product.

(3) Electrical machines such as computers can do data processing, but they do not have consciousness or understanding, and a computer does not have self-hood.

(4) It is fallacious to speak as if work done by an electrical machine is a case of something latent in a machine being unleashed. When my fan runs, it is not because some inherent electricity in the machine is being unleashed; it is because the machine is connecting to a very complicated external power grid.

(5) Mechanical work (a physical moving about of things) bears no resemblance to the aspects of human mentality (which are mental, non-physical things). So if we know that some latent thing inside physical things could give rise to mechanical work, that would do nothing to make it more likely that some latent thing inside a physical thing could give rise to mental phenomena.

The author Julie J. Morley advocates panpsychism in the recent book Future Sacred: The Connected Creativity of Nature. Morley's approach is largely to just cite philosophers who advocated for panpsychism. On page 142 she claims that "sentience exists on every scale." She doesn't seem to put up much of any real philosophical argument for panpsychism, although on page 77 she cites approvingly "nine core arguments for panpsychism" advanced by an author named David Skrbina. The arguments are as follows (the quotes paraphrasing these arguments are from Morley's book):

(1) "Indwelling power. All objects exhibit certain powers or abilities that can be plausibly linked to noetic qualities." This claims is invalid; for example, rocks do not exhibit any such powers or abilities.

(2) "Continuity. A common principle or substance exists in all things." Not much of an argument, because we can believe that such a common principle or substance is not a mental principle or substance.

(3) "First principles. Mind is posited as a fundamental and universal quality, present in all things." This isn't an argument for panpsychism, but just a statement of the idea of panpsychism.

(4) "Design. The inherent self-organizing capacity of physical processes suggests the possibility, if not the likelihood or necessity, of some purposeful intelligence (entelechy) active throughout the physical world." There is no known inherent self-organizing capacity of physical processes. There are things (such as fine-tuned physical constants and fine-tuned biology) which may suggest the likelihood of some purposeful intelligence active throughout the physical world, but you can believe in such an intelligence without believing in panpsychism.

(5) "Nonemergence. It is inconceivable that mind should emerge from wholly mindless matter." The implausibility of such a thing argues against materialism, but does not argue specifically for panpsychism. There are still the possibilities of dualism and idealism (immaterialism) if mind cannot emerge from matter.

(6) "Theology. Omnipresent God, understood as universal 'mind' or 'spirit,' exists in all things." That is an assertion, not an argument.

(7) "Evolution....Certain objects (e.g. plants and the Earth) share a common dynamic or physiological structure with human beings, and thus possess mind." I deny that there is any common dynamic or physiological structure shared by rocks or rocky bodies (such as the Earth and the moon) and human beings. Even plants don't really have any common physiological structure or dynamic with humans.

(8) "Dynamic sensitivity. Living systems...respond dynamically to changes in the environment. This inherent responsiveness implies 'sensitivity' -- an ability to feel and be aware of its surroundings." This could be used to argue that all living things have some kind of consciousness, but does not support the idea that lifeless things such as rocks have consciousness.

(9) "Authority. Major intellectuals have expressed an intuitive or rational belief in some form of panpsychism." The same type of reasoning could be used for almost any belief that was ever advocated in a book.

On page 157 of her book, Morley tells us that sentience is "inseparable from matter" and that matter and mind are "inseparably coupled." This does not match the empirical evidence. It is very common in near-death experiences for someone to report floating out of his body and observing his body from above it. In many such cases a person who should have been unconscious will correctly report observations he should have been unable to have observed while unconscious. Such experiences suggest quite the opposite of a dogma that mind is inseparable from matter. Speaking of life-after-death, since a panpsychist believes that all matter is conscious, and that mind is inseparable from matter, panpsychism would seem to imply the ghastly idea that corpses are conscious inside their coffins.

Below are two very similar cases of reasoning, equally fallacious. One of them is panpsychism.

| John: The matter in

your brain creates your mind.

Bob: I don't believe it. Why would mere matter give rise to Mind, something totally different? John: So let's just imagine that all matter is conscious. Then you should be able to believe that your brain makes your mind, or is your mind. |

John: I have a rock

in my backyard that can levitate. Bob: I don't believe you. A rock could never levitate. John: So let's just suppose that all rocks can levitate. Then you should be able to believe that the rock in my backyard can levitate. |

I think there's different versions of panpsychism. Some focus more on qualitative experience rather than cognitive functions.

ReplyDeletePlus I think there's difficulties with explaining things because of language barriers and difficulties in defining things. Like what are we defining as 'consciousness' in this context - qualia; sentience; or awareness?

-

Regarding your points on inanimate things like sand or rocks

I don't think a panpsychist would necessarily believe that self-hood, or feelings of boredom or misery, would be occurring in inanimate objects like rocks or sand. There would have to be a certain amount of complexity and sophistication in the arrangement of the material for there to be complex forms of qualia like thoughts, or emotions, self-hood, sensory experience, etc, to occur.

Inanimate things like rocks, biscuits, or sand, also don't have nerves (or impulse signals, and things like that) so I don't think they'd experience pain or any sort of feeling (whereas living creatures do since they have these things).

So, I'd imagine if there's consciousness in inanimate objects like rocks or tables it would be, at best, a really bare bones type of sentience, or something like that. Perhaps like a dreamless sleep, or something very very basic.

-

Regarding what you said here

"One alternate idea is to assume that we have something like a soul, and that our mental experiences are produced not mainly by matter (the brain), but by something that is itself mental or spiritual."

Couldn't this idea and panpsychism both be true? Like there can be souls that can operate independent of physical matter, and yet also sentience existing in all matter (however they may be)?

It's very unclear what panpsychists are thinking when they try to say inanimate things are conscious. If you are suggesting they think that rocks have some kind of consciousness without self-hood or sensory experience or thoughts or emotions or memories, all I can say is that such a thing would not be any kind of real consciousness, so saying a rock has that isn't really saying anything.

ReplyDeleteI suppose there could be both human souls and also consciousness in all matter, although believing in both of these things would seem to make little sense. Panpsychism is mostly a clumsy attempt to deal with the many failures of the "brains make minds" idea. Panpsychists use shrink-speaking to try to shrink the human mind down to some mere shadow of itself, and then they try to kind of say "everything has such a shadow." A much better idea is that humans have minds because they have something like souls, an idea which does not require us to describe human minds as a thousand times less than they are, and does not require the silliness of saying everything is conscious. Trying to postulate both human souls and panpsychism would be like trying to explain someone's death by saying that he was BOTH killed by a lightning bolt and tasered to death by the police. You don't need two explanations for something. You only need one.