One of the hottest topics

in futurology concerns the possibility of what is called a

technological singularity. Those who imagine a singularity postulate

that computers will keep getting faster and smarter, following the

trajectory of Moore's Law (the rule that every two years there is a

doubling of the number of transistors that can be packed on a circuit

board). Before long, it is argued, we will be able to fit the

computing power of a hundred human brains on a single desktop

computer. Presumably this will lead to the emergence of computerized

superintelligence. This emergence of superintelligence (in what is

called an “intelligence explosion”) is referred to as the

singularity.

The term singularity was

popularized by Ray Kurzweil in his book The Singularity is Near.

Kurzweil predicted that this singularity would occur around the year

2045. His book contains quite a few logarithmic diagrams plotting the

growth of computing power over the past twenty five years. Extending

the trend line a few decades into the future, he estimates that

within a few decades the total brainpower of all computers will match

the total brainpower of all humans. Singularity enthusiasts postulate

that soon this “intelligence explosion” will lead to computers

that are far more intelligent than humans. Singularity enthusiasts

also imagine there will before long be a merging between computers

and men, allowing people to have their minds connected to computers

or enhanced by computers.

If someone tries to cite

possible limits to how small silicon chips can be miniaturized,

advocates of a singularity will mention other promising technologies

such as quantum computing and biological computing, which may well

allow Moore's Law to continue for many decades, with computers

basically getting twice as fast and powerful every two years.

However, there is a huge

bottleneck that well may mean that such a singularity does not occur

anywhere near as quickly as its advocates predict. The bottleneck is

software. Large advances in computer intelligence require equal

progress on two different fronts: the hardware front and the software

front. To create a computer as intelligent as a human being, you

would need not only hardware vastly better than anything available

today, but also software thousands or millions of times better than

anything available today.

Unfortunately the annual

progress rate of software is much slower than the annual progress

rate of software. Software development progress does not at all

follow any rule of progress as dramatic as Moore's Law.

At what rate of progress

is software improving from year to year? There is really no exact way

to answer this question. Any answer is a subjective judgment call.

In his book Kurzweil

estimates that software is improving at a rate of doubling in power

every six years. But he provides no reasoning to back up this claim,

and it seems that he just kind of picked the number out of a hat. As

someone who has worked in software development over the past twenty

years, I can say that from a development standpoint it doesn't seem

like software is four times more powerful than it was twelve years

ago. In 1997 programmers would develop programs mainly by using

compilers with graphical user interfaces, the internet, object

oriented languages, and class libraries. That's exactly how

programmers develop software today.

But to be generous to

singularity enthusiasts, let's suppose that figure is correct. If

software doubles in power or excellence every six years, it will

still mean a huge and growing gap between our future advancement in

software and our future advancement in hardware.

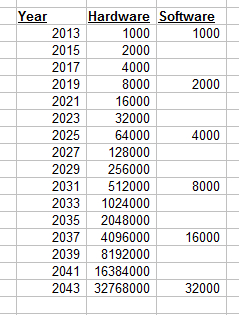

To see how big this gap

is, let's see what figures we get if we double

hardware power every two

years, and double software power every six years.

This table uses a number

of 1000 as an arbitrary starting point.

What we find is that by

the year 2043 computer hardware power has increased by a factor of

32,000 times, but computer software power has increased by only 32

times. The end result is that computer hardware ends up being 1000

times more powerful than computer software.

What does this mean in

practical terms? It suggests that the technological singularity will

not occur anywhere near as quickly as singularity enthusiasts

imagine. We will not at all have anything like superintelligent

machines (or even computers as smart as human beings) if they are

using software that is only 32 times better than today's software.

We probably won't have computers as smart as human beings until we

have software that is many thousands of times better than today's

software.

This gap between the fast

rate of progress of hardware and the slow rate of progress of

software is called the software gap. The software gap may mean that

you won't see any singularity in your lifetime unless you are young.

There are currently singularity enthusiasts in their fifties who

imagine that they will be able to escape death by uploading their

minds into computers or robots, after computers and robots become as

intelligent as people. I have no such hope. I don't think the

software will be ready before I die.

To see Paul Allen's

argument about the singularity (similar to mine), use the link below:

No comments:

Post a Comment