Scientists love to create and defend theories that they claim are solutions to grand mysteries of nature. For a certain type of creative scientist, it is a very enjoyable activity to create a new theory that can be proclaimed as some grand solution to a long-standing mystery of nature. Other scientists (often much less creative scientists) love to play the role of defending some popular theory against challenges. How do such scientists respond to people presenting evidence and arguments against their beloved theories? There are healthy types of responses, semi-healthy types of responses, and unhealthy types of responses.

Healthy Response #1: The Simple Sparse Auxiliary Hypothesis

An auxiliary hypothesis is something added to a theory to handle some objection. When an auxiliary hypothesis is simple and rather sparse, then adding it to a theory need not damage the theory's credibility. For example, suppose you have the theory that UFOs are spaceships from another planet. Then suppose someone objects that most reported UFOs are not all that big, but that to accomplish interstellar travel would require a spaceship that is very big. You can respond to this objection by introducing a fairly sparse auxiliary hypothesis. You simply maintain that when UFOs are seen, they are usually smaller exploratory craft which come from a much larger unseen "mother ship" large enough to travel across interstellar space. That's a fairly sparse auxiliary hypothesis that seems rather plausible. Humans themselves have experience in building landing craft that are moved around by larger units designed purely for traveling through space. For example, the rover vehicles that NASA lands on Mars are carried to Mars by much larger craft. The rockets on a rover vehicle are purely for landing on Mars, and don't take the rover vehicle to Mars.

Unhealthy Response #1: The Extravagant or Overweight Auxiliary Hypothesis, Introduced for Purely "Ad Hoc" Reasons

An unhealthy response by a scientist can occur if he tries to defend his theory by introducing some hypothesis that can be called extravagant or overweight. For example, when astrophysicists were confronted with observations suggesting that the existing theory of gravitation did not correctly predict the rotation speed of stars around the centers of galaxies, astrophysicists created the theory of dark matter, which postulated that the average galaxy is surrounded by a halo of invisible matter heavier than all the matter in such a galaxy. This was a purely "ad hoc" auxiliary hypothesis. The Standard Model of Physics gave no warrant for believing in such invisible dark matter. The dark matter hypothesis meant having to resort to a claim that most of the matter in the universe is invisible, an extravagant claim. A similar situation occurred when astrophysicists responded to a claimed discovery that the universe's expansion was accelerating. Astrophysicists then introduced the "ad hoc" hypothesis of dark energy, that almost all of the mass-energy in the universe is some invisible type of mass-energy called dark energy. The Standard Model of Physics gave no warrant for believing in such invisible dark energy. For a discussion of how dark matter and dark energy claims seem to be examples of unhealthy scientific activity, you can read the paper here. Nowadays the worst example of an extravagant "ad hoc" auxiliary hypothesis is the claim of the multiverse, that there are an infinite or near-infinite number of universes. Such a hypothesis was introduced solely for the "ad hoc" reason of trying to explain away evidence that our universe has very precise fine-tuning of a type that no random universe would ever have. The claim of a multiverse actually does nothing to explain away such evidence, for reasons discussed here and here.

Unhealthy Response #2: Dismiss the Evidence or Case Against the Theory by Claiming That It Is the Reigning Theory

This occurs when a scientist responds to some evidence or case against his theory by appealing to its popularity. Often this unhealthy response occurs in combination with unwarranted or unsubstantiated claims about the popularity of the theory. Scientists are notorious about abusing the word "consensus" in referring to theories. Consensus is a word with multiple meanings, and may be defined as either a unanimous agreement in which everyone holds the same opinion, or merely something believed by a majority. Claims of a consensus of scientific opinion in support of a theory are usually poorly founded and often inaccurate. The only way to reliably measure the opinion of scientists is to do well-designed secret ballot polls including "I don't know" options, and such polls are almost never done. A scientist claiming a consensus in favor of his theory will typically not even have convincing evidence that most scientists believe in his theory.

Unhealthy Response #3: Dismiss the Evidence or Case Against the Theory by Claiming That There Is No Substitute Explanation

This occurs when a scientist responds to some evidence or case against his theory by claiming or implying or insinuating that we must keep believing in the theory because there is no other explanation for what the theory tries to explain. This usually involves the fallacious assumption that scientists cannot go from saying "I understand this phenomenon by means of a theory popular among scientists" to saying "scientists once thought they understood this matter, but now it is clear they do not." There is no reason why such a transition cannot occur, and when such transitions do occur, it is a sign that science is acting in a healthy way. Often the "there's no alternative" claim is untrue, and the situation is that there is an alternative, but one that scientists would prefer not to believe. For example, it may be claimed that there's no alternative to believing that humans evolved through an accumulation of random mutations. There certainly are alternatives, such as believing that man originated with the help of purposeful activity by a superhuman power.

Semi-Healthy Response #1: Make a "Not Very Worried" Response to the Evidence or Case Against the Theory

This occurs when a scientist confesses that there is some force or truth in the evidence or case against the theory, and then tries to minimize the problem by describing this conflict as a mere "potential problem" for the theory, or perhaps a "cloud on the horizon" for the theory, or a "possible worry for the theory."

Semi-Healthy Response #2: Make a "We're Working on a Fix" Response to the Evidence or Case Against the Theory

This occurs when a scientist confesses that there is some force or truth in the evidence or case against the theory, and then tries to minimize the problem by claiming that work is underway to fix the problem.

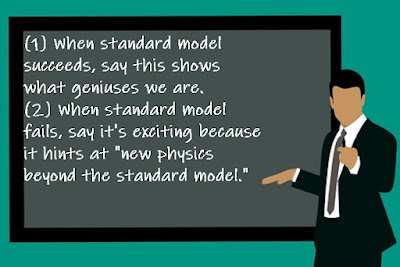

Semi-Healthy Response #3: Vaguely Claim That the Evidence Against the Theory Is Exciting

This occurs when a scientist tries to "make a silk purse out of a sow's ear" by confessing that there is some force or truth in the evidence or case against the theory, but claims that this is "exciting" because it hints at interesting depths of nature that scientists will one day day be able to figure out.

Healthy Response #2: Confess That the Evidence or Case Against the Theory Is Strong, and That the Theory Is Deeply Deficient

One healthy form of concession is to admit that there is some force or truth in the evidence or case against the theory, and to concede that the theory has severe problems and may not be correct.

Healthy Response #3: Confess That the Evidence or Case Against the Theory Is Strong, and the Theory Is Probably Wrong

Another healthy form of concession is to admit that there is some force or truth in the evidence or case against the theory, and to concede that the theory has severe problems and probably is not correct.

Healthy Response #4: Confess That the Evidence or Case Against the Theory Is Strong, and Create a New Theory to Replace It

Although this response often results in the creation of new theories that are just as bad as the old discredited theory, this type of response is basically healthy.

Healthy Response #5: Confess That the Evidence or Case Against the Theory Is Strong, and Strip Down the Theory to Make It Less Pretentious

Another healthy response to evidence against a theory is to restate the theory so that it claims to explain much less than originally claimed. Scientists very rarely practice this healthy response. A good example was when Alfred Russel Wallace published his essay "The Limits of Natural Selection as Applied to Man." Wallace was the co-founder of the theory of evolution, which he originally seemed to regard as a general explanation for the origin of species such as man. But around 1869 Wallace was being exposed to massive evidence for paranormal events that could not be explained by such a theory. Wallace responded with his essay "The Limits of Natural Selection as Applied to Man," making it clear that the theory of natural selection was not an explanation for any of the higher mental faculties of man. He in effect said, "Evolution explains much less than many previously said it did." His wise response has been senselessly ignored by biologists, who continue to make groundless extravagant claims that natural selection explains almost all biology origins.

Unhealthy Response #4: Simply Ignore the Evidence or Case Against the Theory

We see this response massively from neuroscientists who have the theory that the human mind is merely the result of the brain. There is a gigantic mountain of evidence for human mental abilities that cannot be explained by brain activity. Such evidence has been published for literally centuries. Some examples can be found here, here and here. To give one of very many examples I could list, the published evidence is overwhelming that in the nineteenth century Alexis Didier displayed powers of clairvoyance utterly beyond any possible neural explanation. Below is a quote from Alfred Russel Wallace, the co-founder of the theory of evolution, on page 245 of the December 22, 1876 edition of The Spiritualist:

" Dr. Edwin Lee, a well-known physician, in his book on Animal Magnetism, has given, from personal observation, a minute account of the clairvoyance, of Alexis [Didier] at Brighton, which occupies twenty-five pages. Among a great variety of most remarkable tests, he frequently read passages in books brought at random a number of pages in advance of the page opened, but at the level of a line indicated. Numbers of these tests are recorded, the words read always being found at the level indicated, but not always at the exact number of pages in advance asked for. The evidence for this, as well as for many other forms of clairvoyance, is overwhelming, and the tests applied of the most varied and stringent character."

How do neuroscientists respond to all the evidence for ESP and clairvoyance? They simply ignore it. They show zero signs of having seriously studied such evidence. The few that mention such evidence will typically resort to the next item on my list.

Unhealthy Response #5: Make Unfair or "Ad Hominem" Attacks Against Those Presenting the Evidence or Case Against the Theory, Perhaps Resorting to Stereotyping, Gaslighting or Character Assassination

This type of "blame, shame and defame" response occurs massively. Scientists have long engaged in "ad hominem" attacks against those criticizing their theories or those who helped to produce evidence against their theories. This often involves unfair stereotyping in which careful scholars and witnesses are dismissed as kooks or mentally disturbed. Then there are various rhetorical tactics in which attempts are made to associate critics of a theory with some other people who may hold some belief unacceptable to scientists.

Unhealthy Response #6: Dismiss the Evidence or Case Against the Theory, on the Grounds That It Did Not Appear in a Peer-Reviewed Paper

When scientists use this response they sound like some Catholic priest saying "I can't accept your criticisms of Catholicism because they were not published in the Catholic Quarterly." The idea that evidence and reasoning can be ignored because it did not appear in a peer-reviewed paper is one of the most unhealthy and nonsensical responses a scientist can make to criticisms of his theory. Once a theory becomes very popular within some academic community, the theory may become a cherished orthodoxy within some little belief community of scientists; and peer reviewers may then deny publication to papers challenging the theory that is "all the rage" in their little tribe. Under such conditions we would not expect reasoning challenging the thinking of experts of a particular type to be approved by peer reviewers who are experts of that type. Moreover, it is folly to be thinking that sound reasoning and sound evidence only shows up in peer-reviewed papers. In fact, in quite a few scientific specialties, peer reviewers allow an abundance of very poor studies and groundless speculative papers to be published. Nothing could be more fallacious than to insinuate that something is good quality because it is peer-reviewed, or that something is not good quality because it is not peer-reviewed.

No comments:

Post a Comment