It was a bad day recently for a Harvard genetics professor. The Daily Mail ran a story with the headline "Top Harvard professor Dr David Sinclair accused of 'selling snake oil' after pushing 'unscientific' pill said to reverse aging in dogs - and resigns from prestigious academy over backlash." We read this:

"Dr David Sinclair, professor of genetics at Harvard Medical School, has been hit with allegations of pushing bogus antiaging drugs over the last decade - including one he was paid $720 million to develop by pharma giant GlaxoSmithKline. The 54 year-old renowned scientist has made previous claims that he 'reversed' his own age by a decade using unconventional lifestyle 'hacks,' and most recently promoted an 'unscientific' supplement developed by his company that claimed to reverse aging in dogs. But the pill is said to 'not be supported by data,' according to University of Washington aging professor Matt Kaeberlein."

We read this about a study involving dogs:

"The dogs were tracked for six months, with 51 completing the study. Animals in the full-dose group showed slight improvements in cognition as reported by their owners after three months, but the effect was not maintained through six months. However, there was no difference between groups in changes in activity level, gait speed or cognitive tests performed by the researchers.

Dr Sinclair revealed the results on X alongside a promotional image for Leap Year, claiming: 'First-of-its-kind supplement clinically proven to slow effects of aging in dogs. Available at LeapYears.com.'

He shared a hyperlink that took his 441,000 followers to a landing page where they could buy the supplement for $70 to $130 for a one-month supply."

Scientists objected, saying that there was no evidence that the supplement reversed aging. Dr. Matt Kaeberlein was quoted as saying this:

"Dr Kaeberlein, a longevity biologist, wrote on X: 'I find it deeply distressing that we've gotten to a point where dishonesty in science is normalized to an extent that nobody is shocked when a tenured Harvard professor falsely proclaims in a press release that a product he is selling to pet owners has 'reversed aging in dogs.' To me, this is the textbook definition of a snake oil salesman."

Dan Eton, a data scientist at Mass General says, "David Sinclair consistently exaggerates the claims of research that he has a financial stake in. It makes me sick to my stomach."

The study is here. The study group sizes were not 51, but only about 16 per study group. We should not take very seriously any reported evidence of modest cognitive benefits, given the difficulty of measuring cognition in dogs, and the failure of this study to provide convincing experimental tests of dog cognition.

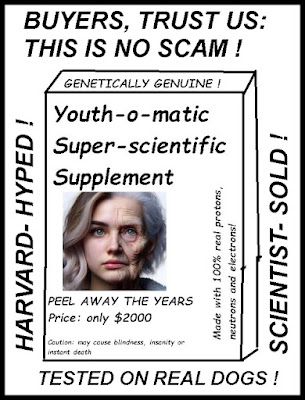

Schematic depiction of next year's anti-aging supplement

The Harvard scientist criticized above (David Sinclair) is co-author (with Yang and others) of a 2023 paper "Loss of epigenetic information as a cause of mammalian aging." The paper makes the very dubious claim that "loss of epigenetic information accelerates the hallmarks of aging," that "these changes are reversible by epigenetic reprogramming," and that "by manipulating the epigenome, aging can be driven forward and backward." These claims are sharply criticized by a critique of the paper, a paper entitled "Matters Arising: the information theory of aging has not been tested." The authors are James A. Timmons and Charles Brenner.

Referring to Yang and Sinclair's paper, Timmons and Brenner say "Extraordinary claims in the paper are unsupported by evidence," and that "no significant conclusion of Yang was demonstrated." They say, "Despite statements in the summary, highlights and discussion and depiction in the graphical abstract, there was also no reversal of aging in the article and indeed, the corresponding author retracted such claims after publication (Supplementary Material 2)." Referring to the journal Cell that the paper of Yang and Sinclair was published in, and recommending that the paper be retracted, Timmons and Brenner say this:

"Cell publishes papers that provide 'significant conceptual advances' on 'an interesting and important biological question.' The journal is not supposed to publish misleading papers that fail to disclose citations and related manuscripts, obfuscate mechanisms, provide poorly controlled experiments, and grandiosely overstate results."

But the truth is that when publishing experimental neuroscience results, the journal Cell very often publishes poorly designed research following Questionable Research Practices, and such papers very frequently "grandiosely overstate results." The "Loss of epigenetic information as a cause of mammalian aging" paper is one with ridiculously small study group sizes such as 2 mice, 3 mice and 4 mice.

I previously mocked the way-too-small study group sizes typically used in neuroscience cognitive research, noting that typically the total number of mice used is only about as big as the number of paper authors, saying that it was if these people were following the ridiculous rule of only using one mouse per scientist. We have that type of situation in this "Loss of epigenetic information as a cause of mammalian aging" paper, which has 58 authors, but sounds like it used a total number of mice much fewer than that. The paper has no mention of a detailed blinding protocol, mentioning blinding only in passing when referring to two tiny fractions of the total work going on. Why do big rich biotech companies work on papers with such ridiculously small numbers of mice and without decent blinding protocols? It sure isn't because they can't afford to test with 100 times more mice. The answer is probably: because it's so vastly easier to get false alarms when you use tiny study group sizes and don't use a decent blinding protocol. And the right type of false alarm can do wonders for the stock price of a biotech company.

Sinclair has got very rich partially by writing a book entitled "Lifespan: Why We Age and Why We Don’t Have To," a book selling millions of copies. A critical review of the book by a scientist (Charles Brenner) states this:

"According to the book, Sinclair discovered genes called sirtuins that extend lifespan in organisms from yeasts to humans and he found sirtuin activators in red wine and elsewhere. Why do we age? Sinclair’s theory is poor information transmission that can be fixed by greater sirtuin function. Why we don’t have to age? He says that we can take sirtuin activators every morning and soon, we’ll take chemicals that will safely reprogram our genes to restore youthful vigor.....Do sirtuins extend lifespan in yeast, invertebrates and vertebrates? Has Sinclair discovered sirtuin activators? Based on 25 years of work by academic and industrial investigators, the clear answer to both questions is no (Brenner, 2022b).....In the accompanying Lifespan podcast, Sinclair makes innumerable non-evidence based statements about benefits of time-restricted eating, statements about age-reversal as evidenced only by changing biomarkers (Fahy et al., 2019), and even potential immortality by repeatable drug treatments. The latter statements were particularly shocking because one of the drugs used to lower biomarkers of aging was growth hormone, which is clearly defined by genetics as a pro-aging molecule (Bartke, 2021).....Sinclair’s attempts to commercialize scientific discoveries have an abysmal track record—these include the multibillion dollar investment of GSK in his sirtuin story (Schmidt, 2010) and Ovascience, whose work in female fertility could not be replicated (Powell, 2006; Weintraub, 2016). For scientific discoveries to be developed they need to be real but for books to sell, the stories just have to be good. The reach of Lifespan is a problem for the world precisely because a Harvard scientist is telling fictitious stories about aging that go nowhere other than continuing hype as legendary as anything in Herodotus."

Who's right and who's wrong here? I'll let the reader judge that. I do know from a long and very careful study of DNA that the idea that DNA or its genes are a "program" for either making or maintaining cells is a great big lie. DNA and its genes contain only low-level chemical information. DNA and its genes have no information on human anatomy, and do not even specify how to make or maintain any cell or any of the organelles that are the building components of a cell. So the idea that cells can be rejuvenated by medicine-induced "cellular reprogramming" seems pretty fishy. Scientists cannot even currently explain how a cell is able to reproduce. How there occurs the reproduction of something as enormously complex and organized as a human cell is a mystery very far over the heads of scientists. So what confidence can we have in scientists talking about "cellular reprogramming"?

Biologists frequently underestimate the vast hierarchical complexity of human bodies, and very frequently speak as if they were trying to prevent the public from learning about such exquisite complexity, possibly because they may realize that the credibility of their claims of accidental biological origins is inversely proportional to the amount of fine-tuned organization and functional complexity of large organisms such as humans. The more we properly understand the stratospheric levels of fine-tuned organization and hard-to-achieve complexity of human bodies, the less confidence we will have that scientists are anywhere near to being able to roll back aging by fiddling with so-called "cellular reprogramming."

An MIT Technology Review article in 2022 says this about claims that the lifespan of some mice have been extended by cellular reprogramming:

"So far, many of these individual rejuvenation claims for live mice haven’t been widely replicated by other labs, and some people are skeptical they ever will be. Measuring the relative health of animals or their tissues isn’t necessarily a precise science. And in unblinded studies (where the researchers know which animals were treated), wishful thinking can play a role, perhaps especially if billions in venture capital dollars ride on the result. 'Frankly, I doubt the reproducibility of these papers,” says Hiro Nakauchi, a professor of genetics at Stanford University. Nakauchi says he also created mice with Yamanaka factors, but he never saw any sign they got younger. He suspects that some of the most dramatic claims are 'timely and catchy' but that the science that went into them is 'not very accurate.' "

From my careful study over many years of flaws in rodent studies wrongly claiming evidence of neural memory storage, I know some of the pathways of errors that can occur here:

(1) Scientists with very large funding are free to do innumerable studies, and may file away all negative results, not even submitting them for publication. Research practices for rodent studies tend to be poor, with a very common occurrence of Questionable Research Practices.

(2) The number of mice used in such studies is typically very small, creating a significant chance (maybe 1 in 20) of "statistically significant" results in any one study, even if no real effect is involved.

(3) With so many studies being done, it's easy to get something like a study showing some mice with higher lifespan. You can just get chance results, file away in your file cabinet the unsuccessful results, and submit for publication the luckiest results.

Consequently, it means very little that some 3 billion dollar biotech company has a few studies showing a few mice lived longer than average when given some treatment. How many negative studies does it have filed away in its file cabinets, using the same methods?

There is still the possibility that there might be treatments that partially reverse aging. Part of aging is relatively uncomplicated stuff like the plaque that builds up in your arteries, like the gunk that slowly builds up in your kitchen drainpipe. Reversing that may be relatively simple. But something like that is totally different (and vastly simpler) than "cellular reprogramming."

Someone as old as me is old enough to remember that for 50 years scientists have been making claims that reversing or stopping aging was "right around the corner." It seemed that for twenty years we were told that the key to stopping aging was just to shorten something called telomeres that are found on the ends of chromosomes. For decades we were told that there would soon be some medicine that would shorten telomeres to halt or stop aging.

You don't hear too much about telomeres these days.

Nowadays scientific papers have a very inadequate listing of the vested interests of the authors. After the end of the main text of the 2023 paper "Loss of epigenetic information as a cause of mammalian aging" in fine print we have a "Declaration of Interests" statement that refers to the massive vested interests of David A. Sinclair, noting "D.A.S. is a consultant, inventor, board member, and in some cases an investor in Life Biosciences (developing reprogramming medicines), InsideTracker, Zymo, EdenRoc Sciences/Cantata/Dovetail/Metrobiotech, Caudalie, Galilei, Immetas, Animal Biosciences, Tally Health, and more." What is with the initials, which makes it hard for people to realize the conflict of interest involved? What should occur is that at the very beginning of a paper written by an author with vested interests, we should have a large-type boldface plain English statement such as this:

"NOTE: One of the chief authors of this paper (John F. Schmitzenholzer) has major stock investments in a company (XYZ Products, Inc.) that will financially benefit very much from the claims made in this paper, and that person receives large sums of money from that company. The same thing is true for most of the authors of this paper."

I can describe one big piece of statistical funny business that commonly occurs in scientific papers on so-called cellular reprogramming. It is what you can call the "remaining lifespan" trick. It works like this: you try some treatment on a small group of some very old mice, and even if the treatment has no benefit, there will be about 1 chance in 10 that you will be able to report that the treated mice had a significantly larger "remaining lifespan" than the untreated mice. In captivity mice can have lifespans range from 6 to 18 months, or in some cases as long as 3 years. So if you start testing with very old mice, you can easily get variations in "remaining lifespan" of up to 200%, merely by chance.

Consequently, we should not be impressed at all by the results in the paper here, which claims that some treatment on mice "extends the median remaining lifespan by 109% over wild-type controls." The study started out with a treatment group of about 19 very old mice that were 124 weeks old, and a control group of about the same size and age (Figure 1C). The mice lived on for between 3 weeks and 40 weeks, with the average remaining lifetime being about 15 weeks. About 13 out of 19 of the treated mice had a remaining lifespan greater than the average. By using a binomial probability calculator such as the one at Stat Trek, you can see that this is a result that you might expect by chance (using a completely ineffective treatment) in about 8% of experiments like this:

We should regard the reported result as being unimpressive when we consider that scientists are free to try experiments such as this mouse study many times, placing in their file drawers unsuccessful results, and submitting for publication results that reach about this level of success. So given many biotech companies funding experiments of this type, we would expect to have multiple published results about as impressive as this one, even if the treatments have no effectiveness.

We can get the real story here by considering not the tending-to-fool-you statistic of "increase in remaining lifespan" but the statistic of total lifespan. The treated mice had a total lifespan of about 144 weeks, and the untreated mice had a total lifespan of about 136 weeks. The treated group of mice therefore had a total lifespan that was only about 6% greater than the untreated mice. But rather than reporting this statistic (which gives us the real story on how slight are the results), the paper has used the "remaining lifespan" trick to tell us the technically correct but very "give you the wrong idea" statistic that the "remaining lifespan" was 109% greater in the treated mice.

But perhaps I am being too pessimistic about such cellular reprogramming. I cannot claim to be a careful scholar of anti-aging research. I have spent many years very carefully studying the evidence that the human mind is not the product of the human brain, and evidence for psychical phenomena and paranormal phenomena that suggest humans are souls that will survive death (as you can see in my 198 posts here). Such evidence leaves me thinking that aging and death are nothing to fear.

Postscript: See my earlier post "The Lesson of the Telomere Myth" for more about how scientists specializing in anti-aging methods misled us for a long time about telomeres. Two of them predicted in 2011 that aging would be cured by about that year. The Wall Street Journal has a post about Sinclair's claims here, one entitled "Star Scientist’s Claim of ‘Reverse Aging’ Draws Hail of Criticism."

No comments:

Post a Comment