I was rather surprised to see on the site The Conversation an article by philosopher Philip Goff entitled "Many physicists assume we must live in a multiverse – but their basic maths may be wrong." I was surprised because The Conversation site (https://theconversation.com/) tends to serve up materialist propaganda, but in this case we had an article trying to debunk the idea (currently popular among many materialists) that the idea of a multiverse (some vast collection of universes) does something to explain the very precise fine-tuning of our universe.

For several decades scientists have discovered more and more examples suggesting our universe is seemingly tailor-made for life. A list of many examples is discussed here. One dramatic example is the fact that even though each proton in our universe has a mass 1836 times greater than the mass of each electron, the electric charge of each proton matches the electric charge of each electron exactly, to twenty decimal places (the only difference being that one is positive, the other negative). Were it not for this amazing "coincidence," our very planet would not hold together. But scientists have no explanation for this coincidence which seems to require luck with a probability of less than 1 in 100,000,000,000,000,000,000. As wikipedia states, “The fact that the electric charges of electrons and protons seem to cancel each other exactly to extreme precision is essential for the existence of the macroscopic world as we know it, but this important property of elementary particles is not explained in the Standard Model of particle physics.” In his book The Symbiotic Universe, astronomer George Greenstein (a professor emeritus at Amherst College) says this about the equality of the proton and electron charges: "Relatively small things like stones, people, and the like would fly apart if the two charges differed by as little as one part in 100 billion. Large structures like the Earth and the Sun require for their existence a yet more perfect balance of one part in a billion billion." In fact, experiments do indicate that the charge of the proton and the electron match to eighteen decimal places.

The idea of the multiverse is to hypothesize that there is some infinity or near-infinity of universes, each with different laws of physics and fundamental constants. The multiverse reasoner then claims that with so many universes, we would expect that at least one would have accidentally had the conditions needed for life. There are many reasons for rejecting this line of reasoning, which I explain in my posts here and here. Goff's attempt at debunking multiverse reasoning involves a claim that multiverse reasoning commits a fallacy called the inverse gambler's fallacy. Goff states this:

"Suppose Betty is the only person playing in her local bingo hall one night, and in an incredible run of luck, all of her numbers come up in the first minute. Betty thinks to herself: 'Wow, there must be lots of people playing bingo in other bingo halls tonight!' Her reasoning is: if there are lots of people playing throughout the country, then it’s not so improbable that somebody would get all their numbers called out in the first minute.

But this is an instance of the inverse gambler’s fallacy. No matter how many people are or are not playing in other bingo halls throughout the land, probability theory says it is no more likely that Betty herself would have such a run of luck....

Multiverse theorists commit the same fallacy. They think: 'Wow, how improbable that our universe has the right numbers for life; there must be many other universes out there with the wrong numbers!' But this is just like Betty thinking she can explain her run of luck in terms of other people playing bingo. When this particular universe was created, as in a die throw, it still had a specific, low chance of getting the right numbers."

It seems to be correct that multiverse reasoners are committing the inverse gambler's fallacy. But an analogy such as Goff gives here is not a very good one to match the situation regarding our seemingly fine-tuned universe and ideas of a multiverse. In an analogy like Goff's the relevant elements are these:

(1) A case of extremely improbable luck which was due purely to random chance.

(2) The idea that we can explain this very improbable success by assuming a very large number of random trials (like are sometimes known to occur), in which one case of such luck would be expected to occur by chance.

There are two reasons why Goff's "Betty's gambling" analogy is not a close analogy for the case of our universe's seemingly fine-tuned fundamental constants and laws, and appeals to a multiverse to explain such fine-tuning:

(1) We do not know that our success of a habitable universe (so mathematically improbable to occur by chance) did occur by chance or by design. So Betty's gambling luck at the end of playing bingo (which Goff says occur "in an incredible run of luck") is not a good analogy for our universe's apparent fine-tuning, which could be the result of either design or chance.

(2) Since bingo is a rather popular game in the United States, it is known that there are "lots of people playing bingo in other bingo halls tonight"; so using such a claim to explain Betty's bingo luck would involve appealing to a known truth. But it is certainly not known that there are any other universes with different fundamental constants or any other universes of any type, so appealing to some vast infinity or near-infinity of universes is nothing like appealing to a known truth, but is instead appealing to some fantastically extravagant hard-to-believe claim.

I can think of a better analogy that is a closer match to the situation involving our universe's seemingly fine-tuned laws and fundamental constants, and attempts to explain that by postulating a multiverse. The analogy is this:

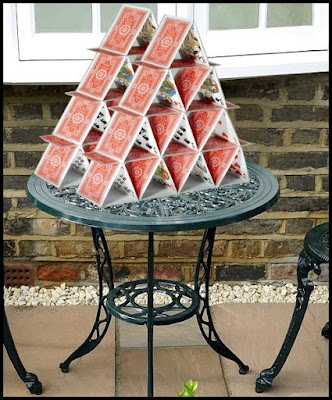

(1) Let in by Walter's daughter Jane, Daniel visits the house of an old man named Walter, and sees that on a table in Walter's house is an arrangement of cards vastly improbable to occur by chance: a triangular house of cards. On the walls are some paintings, which Jane says her father Walter painted.

(2) Daniel then concludes that because it is so improbable that such an arrangement of cards would occur by chance, Walter must have been throwing a deck of cards into the air many times every day throughout his life, and that he stopped doing this when the thrown cards finally formed into a house of cards.

(1) The very well-arranged house of cards (so vastly improbable to arise by chance) resembles our seemingly fine-tuned universe, both in that the success is incredibly unlikely to occur by chance, and also in that we are not sure whether the result occurred by chance or by design. Walter's house of cards looks like something the result of very careful willful arrangement, but it conceivably could have occurred through some vastly improbable stroke of luck, after Walter threw the deck of cards into the air. Similarly, with so many "just-right" fundamental constants and laws allowing the existence of intelligent observers, our universe looks like something the result of very careful willful arrangement, but it conceivably could have occurred through some vastly improbable luck.

(2) Just as multiverse reasoners attempt to explain our seemingly fine-tuned universe by appealing to the wildly extravagant and far-fetched speculation of some vast number of random trials (each the appearance of a different universe with different fundamental constants and laws), Daniel has tried to explain the seemingly well-arranged set of cards (a triangular house of cards) by appealing to a wildly extravagant and far-fetched speculation involving some vast number of random trials (by speculating there was a vast number of cases in Walter's life in which he threw a deck of cards into the air).

Now we have a better analogy for multiverse reasoning than Goff's analogy about Betty's gambling success. And we can more clearly see the folly of multiverse reasoning. It makes no sense for Daniel to postulate the occurrence of some vast number of events of throwing a deck of cards into the air to try to explain the well-arranged house of cards. A much better explanation is that the well-arranged house of cards occurred because of deliberate willful arrangement. Similarly, it makes no sense to try to explain a seemingly very fine-tuned universe by postulating some infinity or near-infinity of random universes. A far simpler and more intelligent explanation is that our universe's seemingly fine-tuned laws and fundamental constants exist because of the purposeful arrangement of some power capable of such an effect.

You may ask: why did I include in my analogy a mention of Walter's daughter Jane mentioning that some paintings on the wall were made by Walter? In my analogy such a thing is prima facie evidence that Walter has previously produced artistic arrangements. We don't know whether Jane is telling the truth. She might be lying, or maybe Walter told her a lie when he said he made the paintings. But the paintings are an important clue, because they provide at least prima facie evidence that Walter previously produced artistic arrangements rather like that of the house of cards. In the light of such prima facie evidence, it is all the more unreasonable to postulate that Walter spent a lifetime throwing a deck of cards into the air as the explanation for the house of cards, rather than assuming that Walter deliberately arranged the house of cards.

The existence of such paintings providing such prima facie evidence is analogous to some evidence we have that is very relevant to the issue of whether the universe's laws and fundamental constants were deliberately arranged. What I refer to are the very many reasons for suspecting the existence of some higher power that could have been involved in a purposeful activity, other than the universe's fine-tuned fundamental constants and fine-tuned laws of nature. Such reasons include the following:

(1) The sudden origin of the universe about 13 billion years ago, currently not explained by any credible theory.

(2) The existence of extremely precise fine-tuning in the origin of the universe, such as a very precise fine-tuning of the universe's early expansion rate, needed for the formation of galaxies.

(3) The occurrence on Earth of an origin of life requiring the very special arrangement of more than 20,000 amino acids (the very special arrangement of more than 200,000 atoms), an event inexplicable through any idea of so-called natural selection (since so-called natural selection requires life to first exist before it can occur), and also inexplicable through any theory of lucky chemical combinations (as the luck would require luck too unlikely to ever occur in the history of the universe).

(4) The appearance of billions of different types of protein molecules in earthly organisms, each a fine-tuned arrangement of hundreds or thousands of amino acid parts, events not credibly explained by Darwinian evolution because of the very high functional thresholds of protein molecules, preventing them from arising by any process by which hundreds of tiny changes (each useful) occur.

(5) The appearance of countless type of mammals with incredibly complex structures and vastly organized fine-tuned arrangements of matter, appearances not explicable by imagining lucky DNA mutations, because DNA does not actually specify the anatomy of any large organism or any of its organs or cells.

(6) The appearance of human minds, with a wealth of mental capabilities and experiences that cannot be credibly explained as being caused by brain activity, for the reasons discussed in the many posts of my blog here.

The six items above at the very least provide us with prima facie evidence for suspecting the existence of some higher power of enormous intellect, which might help to explain some of the items above. So having such prima facie evidence, we are like the Daniel of my analogy. Told by Jane that paintings on the wall were made by Jane's father, Daniel has prima facie evidence that Jane's father Walter is someone who previously engaged in skillful artistic arrangement. So seeing the house of cards looking so much like a deliberate artistic arrangement, it would be folly for Daniel to explain such an arrangement by assuming a lifetime of throwing cards into the air, rather than some deliberate act of arrangement. It is equally great folly to be pondering our universe of seemingly fine-tuned laws and fundamental constants, and trying to explain them not as a result of purposeful arrangement but by appealing to some infinity or near infinity of random trials (particularly given so much other evidence giving us reasons for suspecting purposeful arrangement or causation by a power higher than man).

What senselessly goes on is that materialists restrict their consideration to only physics when they should be considering all of the evidence. They may say to themselves, "This is a matter of physics, so let us only consider physics." That makes no sense. When biology and chemistry and physics and psychology and parapsychology and cosmology are all giving you evidence relevant to some consideration, you should be considering all of that evidence collectively, rather than "looking through a straw-hole" and considering only physics. After considering all of the relevant evidence from biology and chemistry and physics and astronomy and psychology and parapsychology and cosmology, we are left with extremely strong reasons for suspecting some higher power involved in fine-tuning our universe and biology in it, to produce or help produce a huge variety of purposeful and enormously stunning and awe-inspiring end results; and in the light of such reasons a multiverse explanation for cosmic fine-tuning is unreasonable and needlessly super-extravagant.

The principle of very carefully studying and considering all of the possibly relevant evidence is one that you might called "the panoramic principle," as it involves studying and pondering what you see in all directions, like some person very carefully studying what he sees in all directions from the high panorama of a mountain height. If you have one of the Big Questions, following the panoramic principle works much better than following a "straw-hole strategy" of very narrowly focusing your attention, like some person looking through a straw hole. In the posts of this blog and another blog of mine, you will find evidence that I have spent huge amounts of time studying and pondering evidence from an extremely wide variety of fields, including neuroscience, parapsychology, psychology, biology, physics, chemistry, astronomy, cosmology and reports of various types of paranormal phenomena. So a reader might think that I have been following or trying to follow this "panoramic principle" that I refer to, rather than following some "straw-hole strategy" of narrowly concentrating my attention.

No comments:

Post a Comment