It used to be that scientific data was gathered in notebooks, making it relatively inconvenient for scientists to share data. If you were a scientist with 20 notebooks containing experimental observations, you might be reluctant to loan such notebooks to someone wishing to examine your data. You could make photocopies of all of your notebooks, but that might be quite the little chore. But excuses for sharing data pretty much dissolved once the great majority of scientists started recording data using electronic records, using software such as spreadsheets and database programs. For example, if you have a spreadsheet listing 1000 observations, then it is a very simple thing to make a copy of that file, and email that copy to someone who asks to see your data.

It is also extremely easy nowadays for any scientist to publicly share all of their original source data. We are far indeed from the early days of the Internet, when you needed to hire some pricey web programming ace to present your data online. Nowadays there are a variety of free online facilities that make it a breeze to publish any kind of data, even if you know nothing about programming. An example is the Blogger software used to make this blog. That system makes it very easy to publish dated posts that can be rich in tables and photos. After logging into www.blogger.com, anyone with a Google account can create any number of blogs, each of which can have any number of posts, each of which can have any number of tables and photos. Each post has its own unique URL, which helps to facilitate data sharing.

Consequently, there have been more and more demands for scientists to be sharing all of the data that underlies their papers. Many have said that there is no reason why most scientists should not be publishing all of their data online whenever they publish a paper, rather than merely writing up some paper summarizing such data. Many scientists have responded by publishing all of their data online when one of their studies has been published. But far more often scientists will merely offer a promise to make such data available when someone requests it. Given the ease of publishing data these days online, we should be extremely suspicious about such promises. Since it is such a breeze these days to publish data online, why would someone not publish his source data online if he was willing to share it?

The leading science journal Nature has recently published an article giving the results of an effort to determine how many of these promises to make data available upon request are as worthless as a politician's promise to always tell the truth. It should come as no surprise to anyone that the great majority of scientists who claim to make their data available upon request do not actually honor such requests when they are made. In the article we read this:

"Livia Puljak, who studies evidence-based medicine at the Catholic University of Croatia in Zagreb, and her colleagues analysed 3,556 biomedical and health science articles published in a month by 282 BMC journals....The team identified 381 articles with links to data stored in online repositories and another 1,792 papers for which the authors indicated in statements that their data sets would be available on reasonable request. The remaining studies stated that their data were in the published manuscript and its supplements, or generated no data, so sharing did not apply. But of the 1,792 manuscripts for which the authors stated they were willing to share their data, more than 90% of corresponding authors either declined or did not respond to requests for raw data (see ‘Data-sharing behaviour’). Only 14%, or 254, of the contacted authors responded to e-mail requests for data, and a mere 6.7%, or 120 authors, actually handed over the data in a usable format. The study was published in the Journal of Clinical Epidemiology on 29 May."

The article mentions some mostly ridiculous "dog ate my homework" kind of excuses for reluctance to share data:

"Researchers who declined to supply data in Puljak’s study gave varied reasons. Some had not received informed consent or ethics approval to share data; others had moved on from the project, had misplaced data or cited language hurdles when it came to translating qualitative data from interviews."

These are all pretty ridiculous excuses. Specifically:

(1) "Misplaced data" is an excuse that is an admission of professional incompetence. Any researcher carrying on his affairs competently will be able to easily back up his data in multiple places, so that there will be no possibility of losing data by misplacement.

(2) "Language hurdles" is not a viable excuse in these days of Google Translate. Source data can be supplied in a non-English language, and the person wishing to translate the data can go to the trouble of using Google Translate to translate the data into the preferred language.

(3) Because sharing data gathered in electronic form is a "breeze" not requiring much effort, an excuse of having "moved on from the project" is not a substantial one. Experimental source data should be published online as part of the job of doing an experiment, meaning there will be no need to ask for work from scientists who have "moved on from the project" after the project has finished.

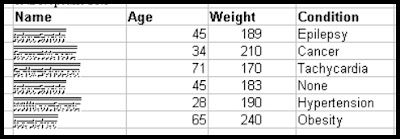

(4) "Informed consent" is not a substantial excuse, because there are so many simple ways of hiding patient names or subject names when presenting source data. Below is one example. A column containing patient names is simply formatted so that the patient names are illegible:

We should suspect that the main reason why so many scientists are reluctant to share their source data is because sharing such data would allow independent analysts to discover that the scientists engaged in Questionable Research Practices or drew unwarranted conclusions from their data. Many scientists write scientific papers that have titles, summaries or causal inferences that are not justified by the data in the papers. A scientific study found that "Thirty-four percent of academic studies and 48% of media articles used language that reviewers considered too strong for their strength of causal inference." A study of inaccuracy in the titles of scientific papers states, "23.4 % of the titles contain inaccuracies of some kind." A scientific study found that 48% of scientific papers use "spin" in their abstracts. An article in Science states that "more than half of Dutch scientists regularly engage in questionable research practices, such as hiding flaws in their research design or selectively citing literature," and that "one in 12 [8 percent] admitted to committing a more serious form of research misconduct within the past 3 years: the fabrication or falsification of research results." In a survey of animal cognition researchers, large fractions of researchers confessed to a variety of procedural sins. I know from my long study of neuroscience research that the use of Questionable Research Practices in cognitive neuroscience is a runaway epidemic, and I estimate that a very large fraction or a majority of research papers in cognitive neuroscience are guilty of one or more types of Questionable Research Practices.

We should not let research scientists get away with "the dog ate my homework" kind of excuses listed above for their failure to publish their original source data. Nowadays the electronic publication of data is so easy that there is no excuse why experimental scientists should not be publishing all of their original source data. A good general rule to follow is to simply disregard or question the reliability of any experimental study that fails to publish all of its original source data. Just as any properly designed building will have room exits and smoke detectors, any properly designed experimental study will be one that makes it possible for the researchers to conveniently publish all of their original source data without much additional hassle. If a study was incompetently designed so that its original source data cannot be publicly published, we should suspect that there were design defects in the study, and that it is not reliable. Similarly, if a building is incompetently designed so that people will not be warned of a fire promptly and cannot speedily escape a fire, we should suspect that the building has other design defects that make it unsafe for habitation.

No comments:

Post a Comment