The problem lies with our science professors. Science professors are often members of a conformist belief community in which there are hallowed belief dogmas and very strong taboos. We fail to realize how often science professors are members of tradition-driven church-like belief communities, because so many of the dubious belief tenets of such professor communities are successfully sold as "science," even when such tenets are speculative or conflict with observations. Fairly discussing reports of the paranormal is a taboo for science professors, who are typically men whose speech and behavior is dominated by moldy old customs and creaky old taboos. There are many other socially constructed taboos such as the taboo that forbids saying something in nature might be a product of design, no matter how immensely improbable its accidental occurrence might be. The main reason why science professors shun reports of the paranormal is that such reports tend to conflict with cherished assumptions or explanatory boasts of such professors. Also, reports of the paranormal clash with the attempts of vainglorious science professors to portray themselves as kind of Grand Lords of Explanation with keen insight into the fundamental nature of reality.

One of the rules of today's typical science professor is: shun the spooky. So when people report seeing things that scientists cannot explain, the rule of today's scientists is: pay no attention, or if you mention it, try to denigrate the observational report, often by shaming, stigmatizing or slandering the observer. Following the "shun the spooky" rule, science professors typically fail to read hundreds of books they should have read to help clarify the nature of human beings and physical reality, books discussing hard-to-explain observations by humans.

It is a gigantic mistake to assume that when a science professor speaks against the paranormal, he is stating an educated opinion. Based on their writings, it seems that 99% of today's science professors have never bothered to seriously study the paranormal. A physics professor denigrating the paranormal no more states an educated opinion than a taxi driver offering an opinion on quantum chromodynamics. The fact that a person has studied one deep subject requiring the reading of hundreds of long volumes for a fairly good knowledge of the subject is no reason for thinking that the same person has studied some other deep subject (such as paranormal phenomena) requiring the reading of hundreds of long volumes for a fairly good knowledge of the subject, particularly when studying such a subject seriously is a taboo for that type of person. Serious scholars of paranormal phenomena can tell when someone speaking or writing on a topic has never studied it in depth, and low-scholarship indications are typically dropped in abundance when science professors write about the paranormal (things such as a failure to reference or quote the most relevant original source materials).

The scientist following a "shun the spooky" rule a rule is rather like Sherlock Holmes wearing handcuffs behind his back. Sherlock Holmes was the most famous fictional detective in literary history. In a series of stories by Arthur Conan Doyle, Sherlock Holmes would attempt to uncover the truth behind a crime, using every tool he could muster. Like Sherlock Holmes, a scientist attempts to uncover the truth, using a variety of tools and methods. But imagine if Sherlock Holmes tried to solve crimes wearing handcuffs that prevented him from using his hands. He would probably fail to solve many of his harder crime cases, and would often come up with wrong answers.

The scientist following a "shun the spooky" rule is like a man wearing handcuffs that prevents him from using his hands. A large fraction of the most important clues that nature offers are things that appear to us as spooky things, because we cannot understand them. A scientist refusing to examine such clues will be likely to reach wrong conclusions about some of the most important issues a scientist can study.

It is a great mistake to think that a scientist following a "shun the spooky" rule will merely end up getting wrong ideas about paranormal topics. Following such a rule, the scientist will tend to also end up with wrong ideas about important topics that are not normally thought of as paranormal. The person who fails to study the paranormal will tend to end up with wrong ideas on topics such as the relation between the brain and the mind and the origin of man. Similarly, he who fails to properly study mathematics may end up with wrong ideas on topics outside of mathematics, such as physics and biology; and he who fails to study history may end up with bad ideas about politics, current affairs and public policy.

The "shun the spooky" rule causes neglect of all kinds of important things beyond what is considered paranormal. So, for example, scientists may avoid studying John Lorber's cases that included cases of above-average intelligence and only a thin sheet of brain tissue, finding such results too spooky. Such results are "wrong way" signs nature is putting up, telling neuroscientists some of their chief assumptions are wrong. The "shun the spooky" rule may lead to wasted billions and bad medical practices. Doctors and scientists may focus on ineffective treatments stemming from incorrect assumptions, while neglecting effective treatments because the results are too spooky for them.

When I was a small child, younger than 10, I would read in a children's magazine a series of educational cartoons that were called the Goofus and Gallant series. The Goofus and Gallant series of cartoons would try to teach small children good principles of behavior, by showing bad behavior by Goofus and good behavior by Gallant. I can never recall hearing a word about the Goofus and Gallant series in the past 50 years, nor can I recall ever thinking about such a series in the past 50 years. My ability to accurately remember such details from well over 50 years ago is one of many reasons why I reject prevailing neuroscientist claims about synaptic memory storage, claims that are untenable because synapses don't last for decades, and the proteins in synapses last only about a thousandth (.001) of the longest length of time that humans can accurately retain memories.

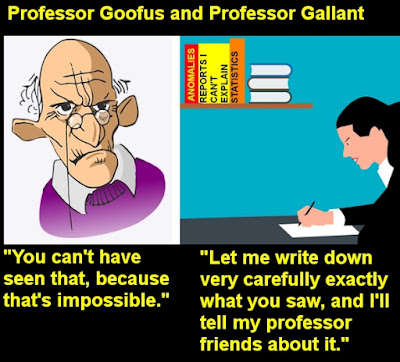

I can use the Goofus and Gallant approach to illustrate some of the differences between bad professor behavior and good professor behavior when dealing with reports of spooky phenomena. Here is one attempt:

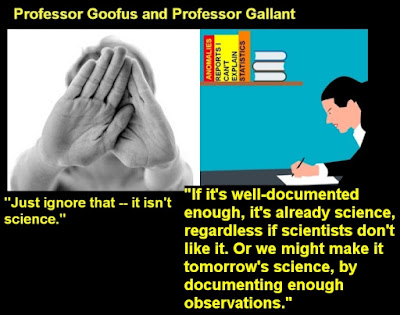

Here is another such attempt:

Here is one more such attempt:

And here is the last such attempt:

Very sadly, the science departments of our universities are all stuffed with guys like Professor Goofus. To these self-shackled Sherlocks, I say: ditch your shackles, and start studying all of the evidence relevant to the claims you make, including the things discussed in my 100+ posts here and the list of books given at the beginning of the post here.

I myself lived in a haunted house during all of my high school years. After that, my wife and I lived in that house for over a year. I never mentioned to her anything about the haunting, but she experienced it on her own. I even heard a man's cough on the phone while talking with her, (she panicked when she heard it), and had to leave work to finally let her in on it. Despite all that, I STILL read reports of ghosts with some skepticism. It turns out that many such reports are hoaxes or illusions. Extraordinary claims require extraordinary proof (which I personally had, but cannot duplicate). Other discoveries in science have applications in technology, but unless and until paranormal phenomena have that, there seems to be at most only minimal advantage to be gained by further research. I'm not saying this is fair, but it is the way of the world so far.

ReplyDeleteI disagree that there is "only minimal advantage to be gained by further research" unless there are "applications in technology." For one thing, research into the paranormal can help clarify fundamental questions about who we are. Also research into the paranormal can have medical applications. Consider hypnosis, which is entangled with the paranormal. Yesterday a BBC article described at length its importance as a medical technique: https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20220519-does-hypnosis-work

DeleteAre you a mere epiphenomenon of neural activity

Delete(like the scent from a cooking soup), a member

of some species that arose only because of

lucky genetic accidents? Or are you a soul

dwelliing for a while in a body? Research into

the paranormal can help clarify which idea is

more credible. And so can a properly-conducted

study of the brain, one that separates the

hype from the facts, one that focuses on

the physical shortfalls of the brain that

conflict with claims commonly made about it.

www.headtruth.blogspot.com