If the person showed you a “house

of cards” consisting of only one card leaning against another card to

make an upside-down “V” shape, you might easily be willing to

believe the person's theory of accidental construction. But suppose

the person showed you a “house of cards” consisting of twenty

cards. You then would be vastly less likely to believe the person's theory

of accidental construction. If the person showed you a “house of

cards” consisting of 50 cards, like the one below, you would never accept any theory

that such an intricate and hard-to-achieve arrangement had occurred

by chance.

Speaking

more generally, I can evoke a general rule: what I can call the first

rule of accidental construction.

The

first rule of accidental construction: the credibility of any

claim that an impressively organized final result was accidentally

achieved is inversely proportional to the number of parts that had to be

well-arranged to achieve such a result, and the amount of

organization needed to achieve such a result.

Because

of this general rule, the rule that the more functionally organized something is the less likely it arose accidentally, there is a very important relation between the

degree of organization and complexity in biological organisms and the

credibility of Darwin's theory of natural biological origins. The

relation is that the credibility of Darwin's theory of natural

biological origins is inversely proportional to the degree of

organization and functional complexity in biological organisms. The more

organized and functionally complex that biological organisms are, the less likely that

they might have appeared because of any accidental process.

Biological

organisms have enormously high levels of organization. We know how to put together piece by piece aircraft carriers equipped with all their jets, but there is no team of scientists that could ever put together from scratch a living human body, by a molecule by molecule arrangement of parts. The human

body has a more impressive degree of organization and complexity than

any machines humans have ever manufactured. So the advocates of

Darwinism have a tough situation. If they realistically depict organisms

such as humans as being as functionally complex and hierarchically organized as they are, all attempts to sell

Darwinism will be undermined. So the advocates of Darwinism routinely attempt

to portray organisms and their parts as being vastly less complex than

they are.

Again

and again (particularly when speaking to the general public), mainstream biologists will give us kind of kindergarten

sketches of biological life, in which organisms or their parts are depicted as

being enormously simpler than they are. They use a series of tricks by which people may be fooled into thinking

that organisms and their parts are a hundred times simpler or a thousand times simpler or a million times simpler than they

are.

To perform such a concealment, biologists very often engage in what I call shrink-speaking, which is misleadingly describing something as if it were vastly simpler than it is. A person who describes the United States of America as "just a bunch of buildings" is engaging in shrink-speaking, as does a scientist who refers to you as "a bunch of chemical compounds." The same shrink-speaking would occur if someone described the volumes of a public library as "just some ink marks on paper."

Below are some of the tricks that are used as part of this

gigantic complexity concealment. The tricks are most commonly used when professors are writing books for the general public or articles designed to be read mainly by the general public. Conversely, inside scientific papers rarely read by the public, professors often discuss the vast amount of organization and functional complexity of living things.

Trick #1: The Frequent

Mention of “Building Blocks of Life”

Scientists

and science writers have long claimed that “building blocks of

life” were produced by certain experiments, although the claims

made along these lines are very erroneous and misleading. More

baloney has been written about the Miller-Urey experiment (an

experiment claimed to have produced “building blocks of life”)

than almost any other scientific topic.

Without

reviewing the huge number of misstatements that have been made about

origin-of-life research, we can merely consider how utterly

misleading is the very phase “building blocks of life.” The very

term suggests that the simplest life would be something very simple.

When we think of what is made from building blocks, we can think of something as

simple as a wall or a simple house made of cinder blocks or bricks.

But all cells are incomparably more complex than a simple house.

The

building blocks of cells are organelles, which make up even the

simplest prokaryotic cells. The building blocks of organelles are

proteins, and the building blocks of proteins are mere amino acids.

Whenever anyone describes an amino acid or a nucleobase as a

“building block of life.” that person is misrepresenting the

complexity of life. An amino acid is merely the building block of a

building block (a protein) of a building block (an organelle) of a

cell.

Trick #2: Misleading

Cell Diagrams

A

staple of biological instruction materials is a diagram showing the

contents of a cell. Such diagrams are usually profoundly misleading,

because they make it look like a cell is hundreds or thousands of

times simpler than it actually is.

Specifically:

- A cell diagram will typically depict a cell as having only a few mitochondria, but cells typically have many thousands of mitochondria, as many as a million.

- A cell diagram will typically depict a cell as having only a few lysosomes, but cells typically have hundreds of lysosomes.

- A cell diagram will typically depict a cell as having only a few ribosomes, but a cell may have up to 10 million ribosomes.

- A cell diagram will typically depict one or a few stacks of a Golgi appartus, each with only a few cisternae, but a cell will typically have between 10 and 20 stacks, each having as many as 60 cisternae.

- Cell diagrams create in the mind the idea of a cell as a static thing, when actual cells are centers of continuous activity, like some active factory or a building that is undergoing continous construction and remodeling.

Trick #3: Claiming that

a Human Could Be Specified by a Mere “Blueprint” or “Recipe,”

and Claiming DNA Has Such a Thing

The

idea that DNA is a blueprint or recipe for making a human being is a

claim that is both false and profoundly misleading, giving people a

totally incorrect idea about the complexity of human being. It is

false that DNA has any such thing as a recipe or blueprint for making

a human. DNA contains only low-level chemical information such as

information about the amino acids that make up proteins. DNA does not contain

high-level structural information. DNA does not specify the overall

body plan of a human, does not specify how to make any organ system

or organ of a human, and does not even specify how to make any of the

200 types of cells in the human body. See this post for

the statements of 18 science authorities telling you that DNA is

not a blueprint or a recipe for making organisms.

Besides

giving us an utterly false idea about the contents of DNA, claims

such as “DNA is a blueprint for making humans” or “DNA is a

recipe for making humans” create false ideas about the

complexity of human beings. A blueprint is a large sheet of paper

for doing a relatively simple construction job. A recipe is a single

page for doing a relatively simple food preparation job. So whenever

we hear people say something “DNA is a blueprint for making a

human” or “DNA is a recipe for making a human,” we think that

the construction of a human is a relatively simple affair. In

reality, a human body is many thousands or millions of times too

complex to be constructed from any blueprint or recipe.

If

you were to give an analogy that would properly convey how complex

would be the instructions needed for building a human, you might

refer to something like a “a long bookshelf filled with many volumes of construction

blueprints" or a “long bookshelf filled with recipe books.” But

even such analogies would poorly describe the instructions for making

a human, as they would be give you the idea of a human being as

something merely static, rather than something that is internally

dynamic to the highest degree.

Trick #4: Trying to

Conceal the Complexities of Human Minds, by Claiming that Human Minds

Are Like Animal Minds

Humans

are enormously complex not only in their physical bodies, but in

their minds. The human mind is its own separate ocean of mental complexity

apart from the ocean of physical complexity that is the human body. Darwinists

have always had the greatest difficulty in accounting for the

subtleties and complexities of human thinking and human behavior.

Very much of our mental activity seems like something inexplicable

under any theory of natural selection. Much of what our minds do

(such as mathematical ability, artistic creativity and philosophical

reasoning) is of no survival value, and cannot be explained under any

reasoning of survival-of-the-fittest or natural selection.

Darwinists

have usually dealt with this problem by taking an approach of

claiming that mentally humans are like animals. Such a claim is

a gigantic example of complexity concealment, a case of trying to

cover-up the complexities of the human mind, by sweeping them under

the rug. Darwin committed this error most egregiously in a passage of The Descent of Man in which he made the extremely absurd claim that " there is no fundamental difference between man and the higher mammals in their mental faculties."

Trick #5: Using the Shrink-Speaking Term "Consciousness" To Refer to Human Mentality

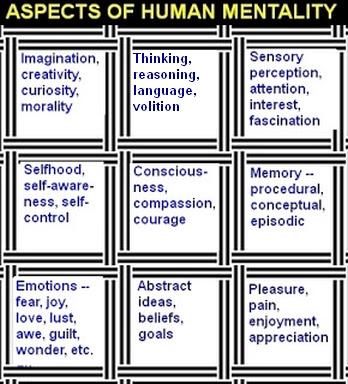

A very common trick of modern scientists is to refer to the human mind (an extremely multifaceted and complex reality) by the minimalist term "consciousness," which would be a suitable term for describing the mind of an insect. A dictionary defines consciousess as being awake and aware of your surroundings. But human mentality is something vastly more complex and multifaceted than that. So using the term "consciousness" for human mentality is an example of shrink-speaking, language that makes something look vastly simpler or smaller than it is.

While the term "problem of consciousness" is often used, what we actually have is not some mere "problem of consciousness" but an extremely large “problem of explaining human mental capabilities and human mental experiences” that is vastly larger than merely explaining consciousness. The problem includes all the following difficulties and many others:

- the problem of explaining how humans are able to have abstract ideas;

- the problem of explaining how humans are able to store learned information, despite the lack of any detailed theory as to how learned knowledge could ever be translated into neural states or synapse states;

- the problem of explaining how humans are able to reliably remember things for more than 50 years, despite extremely rapid protein turnover in synapses, which should prevent brain-based storage of memories for any period of time longer than a few weeks;

- the problem of how humans are able to instantly retrieve little accessed information, despite the lack of anything like an addressing system or an indexing system in the brain;

- the problem of how humans are able to produce great works of creativity and imagination;

- the problem of how humans are able to be conscious at all;

- the problem of why humans have such a large variety of paranormal psychic experiences and capabilities such as ESP capabilities that have been well-established by laboratory tests, and near-death experiences that are very common, often occurring when brain activity has shut down;

- the problem of how humans have such diverse skills and experiences as mathematical reasoning, moral insight, philosophical reasoning, and refined emotional and spiritual experiences;

- the problem of self-hood and personal identity, why it is that we always continue to have the experience of being the same person, rather than just experiencing a bundle of miscellaneous sensations;

- the problem of intention and will, how is it that a mind can will particular physical outcomes.

It is therefore an example of a complexity cover-up and concealment for someone to refer to the human mind as merely "consciousness" or to speak as if there is some mere "problem of consciousness" when there is the vastly larger problem of explaining human minds that are so much more than mere consciousness. Calling a human mind "consciousness" (a good term for describing the mind of a mouse) is like calling a city a bunch of bricks and lumber.

Trick #6: Trying to

Conceal the Complexities of Human Minds, by Denying the Evidence for

Psi and Paranormal Abilities

As you can see by reading the 41 posts here, we have two hundred years of very good observational and experimental evidence for paranormal human abilities such as clairvoyance and ESP, very much of it published in the writings of distinguished scientists and physicians. But the existence of such abilities is senselessly denied by very many of our professors. Denying the reality of psi is essentially a cover-up, a case of sweeping under the rug complexities of the human mind that you would prefer not to deal with it, for the sake of depicting human minds as being much simpler than they are.

Trick

#7: Failing to Describe the Complexity of Typical Protein Molecules or Larger Protein Molecules

When biologists and writers on biology describe protein molecules, they typically tell us that protein molecules have "many" amino acids. But almost never are we given a statement that informs about how complex protein molecules are. It is very easy to do such a thing.

The first way to do such a thing is by simply mentioning that the average protein molecule has about 370 amino acids, and that very many protein molecules consist of more than 600 amino acids. Another way to do this by an analogy. If we compare an amino acid to a letter, we can say that the average protein has the information complexity of a well-written paragraph, and that the larger protein molecules have the information complexity of a well-written page of text.

But we almost never are told such facts. Nine times out of ten a reader will simply be vaguely told that there are "many" amino acids in a a protein. The complexity of protein molecules are almost always hidden from readers, who may go away with the very incorrect idea that a protein molecule consists of only 10 or 20 amino acids.

When biologists and writers on biology describe protein molecules, they typically tell us that protein molecules have "many" amino acids. But almost never are we given a statement that informs about how complex protein molecules are. It is very easy to do such a thing.

The first way to do such a thing is by simply mentioning that the average protein molecule has about 370 amino acids, and that very many protein molecules consist of more than 600 amino acids. Another way to do this by an analogy. If we compare an amino acid to a letter, we can say that the average protein has the information complexity of a well-written paragraph, and that the larger protein molecules have the information complexity of a well-written page of text.

But we almost never are told such facts. Nine times out of ten a reader will simply be vaguely told that there are "many" amino acids in a a protein. The complexity of protein molecules are almost always hidden from readers, who may go away with the very incorrect idea that a protein molecule consists of only 10 or 20 amino acids.

Trick #8: Failing to Discuss the Sensitivity of Protein Molecules

There are two ways to get an understanding of how organized and fine-tuned protein molecules are. The first is to learn how many parts they have (typically several hundred amino acid parts). The second is to learn how sensitive such molecules are to small changes, how easy it is to break the functionality of a protein by changing some of its amino acids. Some important papers have been written shedding light on how the functionality of protein molecules tends to be destroyed when only a small percentage of the molecule is changed. One such paper is the paper here, estimating that making a random change in a single amino acid of a protein (most of which have hundreds of amino acids) will have a 34% chance of leading to a protein's "functional inactivation." Such papers tell us the very important truth that protein molecules are very sensitive to small changes, which means that they are exceptionally fine-tuned and functionally organized. But we almost never hear our professors discuss this extremely relevant truth.

Trick #9: Failing to Tell Us Protein Molecules Are Very Often Functional Only As a Part of Protein Complexes Involving Multiple Proteins

Protein complexes occur when a protein is not functional unless it combines with one or more other proteins, which act like a team to create a particular effect or do a particular job. When writing for the general public, our biology authorities conveniently mention as infrequently as they can the extremely relevant fact that a significant fraction of proteins are nonfunctional unless acting as team members inside a protein complex, a fact that makes Darwinian explanations of human biochemistry seem exponentially more improbable. An example is a recent paper estimating the likelihood of photosynthesis on other planets, which very misleadingly refers to photosynthesis as being something with "overall simplicity," conveniently failing to mention that photosynthesis requires at least four different protein complexes, making it something that can only be achieved by extremely organized functional arrangements of matter, incredibly unlikely to ever appear by chance of Darwinian processes.

Trick #10: Not Telling Us How Many Protein Molecules Are in a Typical Cell

How many protein molecules are in a typical cell? I doubt whether one high-school graduate in 10 could correctly answer this question within a factor of 100. Biology's concealment aces are good about hiding this important information from us. The answer (about 40 million) almost never appears in print. We do sometimes hear mention of the fact that the human body contains more than 20,000 different types of protein molecules (each a separate complex invention), but not nearly as often as we should.

Trick #11: Misleading "Cell Types" Diagrams Suggesting There Are Only a Few Cell Types

How many different cell types are there in the human body? Our biologists frequently publish "cell types" diagrams listing only a few types of cells. Such charts cause people to think there are maybe 5 or 10 types of cells in the human body. The actual number of cell types in the human body is something like 200. When did we ever see a diagram suggesting this reality?

Trick #12: Describing Human Bodies As If They Were Static Things, Ignoring the Vast Internal Dynamism of Organisms and Cells

Inside the human body and each of its cells there are a thousand simultaneous choreographies of activity. The physical structure of a cell is as complex as the physical structure of a factory, and the internal activity inside a cell is as complex as all of the many types of worker activities going on inside a large factory. Such a very important reality is almost never discussed by our professors when writing for the public. Such people love to describe cells as "building blocks," as if they were static things like bricks or cinder blocks.

Trick #13: Failing to Describe the Hierarchical Organization of Human Bodies

The organization of organisms is extremely hierarchical. Subatomic particles are organized into atoms, which are organized into relatively simple molecules such as amino acids, which are organized into complex molecules such as proteins, which are organized into more complex units such as protein complexes and cell structures called organelles, which are organized into cells, which are organized into tissues, which are organized into organs, which are organized into organ systems, which (along with skeletal systems) are organized into organisms. You will virtually never read a sentence like the previous one in something written by a professor, and we may wonder that this is because a sentence like that one makes too clear the extremely hierarchical organization of organisms, something many of our biologists rather seem to want us not to know about.

Trick #14: Making It Sound As If Particular Organs Accomplish What Actually Requires Organ Systems and Fine-Tuned Biochemistry

In discussions involving biological origins, our professors often speak as if an eye will give you vision or a heart will give you blood circulation, or a stomach will give you food digestion. But nobody sees just by eyes; they see by means of extremely complicated vision systems that require eyes, optic nerves, parts of the brain involved in vision, and very complex protein molecules. And hearts are useless unless they are working with extremely complex cardiovascular systems that include lung, veins, arteries and very complex biochemistry. And nobody digests food simply through a stomach, but through an extremely complicated digestive system consisting of many physical parts and very complex biochemistry. Our professors do an extremely poor job of explaining that things get done in organisms only when there are extremely complex systems consisting of many diverse parts working like a team to accomplish a particular effect.

Trick #15: Making Scarce Mention of the Countless Different Types of Incredibly Fine-Tuned Biochemistry Needed for Organismic Function

Everywhere biological functionality requires exquisitely fine-tuned biochemistry. But we rarely hear about that in the articles and books of professors written for the general public. An example of such fine-tuned biochemistry is the biochemistry involved in vision, which a biochemistry textbook describes like this:

- Light-absorption converts 11-cis retinal to all-trans-retinal, activating rhodopsin.

- Activated rhodopsin catalyzes replacement of GDP by GTP on transducin (T), which then disassociates into Ta-GTP and Tby.

- Ta-GTP activates cGMP phosphodiesterase (PDE) by binding and removing its inhibitory subunit (I).

- Active PDE reduces [cGMP] to below the level needed to keep cation channels open.

- Cation channels close, preventing influx of Na+ and Ca2+; membrane is hyperpolarized. This signal passes to the brain.

- Continued efflux of Ca2+ through the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger reduces cytosolic [Ca2+].

- Reduction of [CA2+] activates guanylyl cyclase (CG) and inhibits PDE; [cGMP] rises toward “dark” level, reopening cation channels and returning Vm to prestimulus level.

- Rhodopsin kinase (RK) phosphorylates “bleached” rhodopsin; low [Ca2+] and recoverin (Recov) stimulate this reaction. Arrestin (Arr) binds phosphorylated carboxyl terminus, reactivating rhodopsin.

- Slowly, arrestin dissociates, rhodopsin is dephosphorylated, and all-trans-retinal is replaced with 11-cis-retinal. Rhodopsin is ready for another phototransduction cycle.

We hear no mention of such requirements in typical discussions of the origin of vision, nor do we hear a discussion of how vision requires certain protein molecules consisting of hundreds of parts arranged in just the right way. Instead, our professors often speak as if vision could have kind of got started if something very simple existed. Such insinuations are absurdly false.

Such biochemical requirements are all over the place in biology. In general, any physical function of a body requires a vast amount of enormously complicated biochemistry which has to be just right. But you would hardly know such a thing from reading a typical article or book written by a professor. The mountainous fine-tuned biochemistry complexity of every physical operation of living things is rarely mentioned, just as if our professors were trying to portray organisms as a thousand times simpler and less organized than they are.

Darwinism seems to be of very little value in explaining such biochemistry. For example, the thirtieth edition of Harper's Illustrated Biochemistry is an 800-page textbook describing cells, genes, enzymes, proteins, metabolism, hormones, and biochemistry in the greatest detail, with abundant illustrations. The book makes no mention of Darwin, no mention of natural selection, and only a single mention of evolution, on a page talking only about whether evolution had anything to do with limited lifespans.

In papers and textbooks professors may accurately describe the complexities of humans, but so often in books and articles for the public such professors use sentences that can be compared to crude cartoon sketches. Human minds have oceanic depths of complexity, and human bodies have oceanic depths of organization. But very often it is as if reductionist shrink-speaking professors describe such oceanic realities as if they were crummy little puddles.

I would also distinguish between mind and consciousness. They are not the same.

ReplyDelete