Richard Dawkins' book Climbing Mount Improbable is a book trying to persuade

you that blind Darwinian evolution (evolution caused by natural

selection and random mutations) produced pretty much all the

biological complexity we see in the world. The book is centered

around a mountain-climbing analogy. In this analogy, reaching some

height of biological complexity is portrayed as something like

climbing a mountain. The book assures us that Darwinian evolution

is able to climb “even the most precipitous heights” because it

takes the “mildly sloping paths” rather than the hardest steepest

path up the mountain. These paths Dawkins describes (on page 73) as

“gently inclined grassy meadows, graded steadily and easily towards

the distant uplands.” He tells us on page 77 that Darwinian

evolution works by “going round the back of Mount Improbable and

crawling up the gentle slopes.”

This is a very poor

analogy – an inappropriate metaphor. The appearance of a

new type of macroscopic organism involves all kinds of complex parts appearing on

the scene in an incredibly intricate and coordinated way, so that

great functional coherence is achieved. But climbing a mountain does

not involve any type of event in which complex parts are assembled.

Climbing a mountain doesn't even involve complexity. So mountain

climbing is a terrible analogy for achieving some stunning wonder of

coordinated biological complexity.

We can imagine all

type of analogies that would have been more appropriate for

describing blind processes producing complex biological structures.

One such analogy would be the idea of trees in a forest luckily

forming into a log cabin, or stones randomly forming into a stone

house. But such analogies would throw unwanted light on the

difficulties of random processes forming coherent structures. So

rather than using such an analogy, Dawkins has chosen an

inappropriate analogy that seems to have been chosen purely for its

rhetorical advantages.

In this sense he's

followed in the same steps as Darwin, who gave us the inappropriate

metaphor of “natural selection,” a term suggesting incorrectly

that nature chooses things. The metaphor is not literally accurate,

because strictly speaking only conscious agents choose things. The

idea of survival of the fittest can be stated without a metaphor by

using either the term “survival of the fittest” or “differential

reproduction.” So why did Darwin make such use of the metaphorical

term “natural selection”? Probably for the same reason

Dawkins has chosen a mountain-climbing analogy: for rhetorical

advantage. Once a person has been persuaded that the evolution of

incredibly complex machine-like functionality is like

mountain-climbing, the same person might be persuaded that such an

end was easily achieved by “walking up the easy back route,”

because there are often “easy back routes” leading to mountain

tops. But since mountain-climbing doesn't involve even the simplest

combination of parts, you are deluding yourself if you think that

this mountain-climbing analogy is suitable for describing the

appearance of wonderfully coordinated biological machinery.

On page 77 of the

book, Dawkins tries to suggest that Darwinism is not a theory of

chance. He says, “It is grindingly, creakingly, crashingly obvious

that if Darwinism were really a theory of chance, it couldn't work.”

But, of course, Darwinism is a theory of chance, the claim

that the combination of blind chance mutations and natural selection

is enough to produce the origin of new species. As Dawkins says on

page 80, “One stage in the Darwinian process is indeed a chance

process – mutation.” So on one page he talks as if Darwinism

isn't a theory of chance, and a few pages later he's talking as if it is just that.

Dawkins admits on page 81 that

mutations usually have bad effects, not good effects. That is a

severe understatement, and a more candid statement would have been to

say that for every mutation that is helpful, there are hundreds or

thousands that are harmful.

On page 96 Dawkins

tries to suggest the idea of macromutations, that a single mutation

can cause a huge change in an organism. He asks, most ridiculously,

“Couldn't the elephant's trunk have shot out in a single, giant

step?” We know why he wants to suggest this old “hopeful

monsters” idea. If macromutations can occur, then rather than have

to believe that lots of favorable mutations were needed for some

biological innovation (something incredibly unlikely to occur by

chance), we can believe that in some cases a favorable innovation

arose from a single macromutation.

But the evidence

Dawkins gives in support of the idea of macromutations is rather

laughable. He states this on page 96:

Macro-mutations

do happen. Offspring are sometimes born radically, monstrously

different from either parent, and other members of the species. The

toad in figure 3.2 is said by the photographer, Scott Gardner of the

Hamilton Spectator, to

have been found by two girls in their garden in Hamilton, Ontario. He

says that they put it on the kitchen table for him to photograph. It

had no eyes at all on the outside of its head. When it opened its

mouth, Mr. Gardner said, it seemed to become more aware of its

surroundings.

This is laughable as

evidence. The photo he shows is a mutant frog that apparently has no

eyes. Inside the frog's mouth are two little round things that could

be anything – maybe eyes, or maybe something the frog ate, or maybe

two marbles the two girls put in the frog's mouth. The second-hand

claim that the frog “seemed to become more aware of its

surroundings” when it opened its mouth is laughable from an

evidence standpoint. There are, in fact, no known cases of a

proven macromutation that ever produced a useful new feature (visible to the eye) in a

biological organism. Dawkins' frog anecdote smacks of desperation.

Why he is citing some story in the Hamilton Spectator rather than

citing a scientific journal? Darwinist biologist Jerry Coyne

says this about macromutations:

Macromutationism

is the idea that important evolutionary changes between groups were

produced by single mutations with very large effects....The

notion of macromutationism pops up every few years in evolutionary

biology. It’s wrong but it’s resilient.

Two scientists have

noted, “In fact, to our knowledge, no macromutations ...

that gave birth to novel proteins have yet been identified.”

Referring to the

fossil record, on page 106 Dawkins makes the damaging admission that

“Transitional forms are generally lacking at the species level.”

Why should there not be a vast abundance of transitional forms in the

fossil record if Darwinian theory is correct?

One of the great

difficulties in natural history is explaining the origin of flight,

where we have the wing-stump problem. For flight to have appeared, a

transitional species would presumably have to have had a mere wing

stump. But wing stumps are not at all useful, so we cannot explain

the appearance of such a thing by saying that it provided some

survival benefit.

On page 115 Dawkins starts

trying to defend the idea that there is an “easy back path” by

which Darwinian evolution could produce flying species. He says, “One possibility is that true flight grew out of the habit of gliding

between trees, which lots of animals do, even if they don't quite

fly.” On page 118 he suggests that it would have been easy for

gliding to evolve:

In

none of these cases is there any difficulty in finding a gentle path

up Mount Improbable. Indeed, the fact that the gliding habit has

evolved so many times testifies to the ease with which these mountain

paths can be found.

This type of

reasoning is very common among orthodox Darwinists, but it is

fallacious. The reasoning goes like this: it must be easy for blind

evolution to produce Capability X, because Capability X has appeared

numerous times in nature. Such reasoning is fallacious because we

have no way of knowing how many occurrences were produced by a

particular type of process that originated biological complexity.

Consider these possibilities:

Possibility 1:

Species have originated merely through natural selection and random

mutations.

Possibility 2:

Species have originated through the action of some mysterious cosmic

life-force or cosmic programming that acts throughout the universe as

an organizational principle.

Possibility 3:

Species have originated because extraterrestrial spaceships have

periodically arrived and planted new life forms on our planets.

Possibility 4:

Species originate when new types of life stray into our planet after

spacetime wormholes open up leading from some other dimension to our

planet.

Possibility 5:

Species originate because some divine creator or angel causes them to

appear.

Possibility 6:

We are living in a computer simulation created by extraterrestrials, and all fossils found are simply details added by them as kind of "backstory details" to flesh out the simulation.

Since we don't know

which of these is true, we cannot appeal to the fact that some

feature exists in multiple life forms as something that helps to

substantiate any of these claims; because such a thing might happen

under any one of these scenarios. In the case of gliding, we have no

known cases of gliding that have been proven to have been produced by

natural selection and random mutations. So the mere fact that gliding

has appeared in multiple species does nothing to support the claim

that gliding could have easily appeared by natural selection and

random mutations.

There are, in fact,

very strong reasons for believing that a feature such as gliding

could not have appeared through natural selection and random

mutations. Let us consider the nature of gliding. Gliding between

trees or branches requires an incredibly precise coordination between

muscles, bones, web-like structures between limbs, eyes, and brain –

for animals must not only land on a distant tree branch, but also be

able to land on the branch without falling. If that coordination

isn't just right, it will be very harmful or suicidal for an animal

to try to glide between trees; for the animal will fall to the

ground. Developing gliding is similar to developing a suspension

bridge, in the sense that until the functionality is almost

completed, what you have is functionality that will be suicidal if

you try to use it. The table below illustrates the point.

| Gliding | Suspension Bridge | |

| 25% Completion | Suicidal (jumping causes animal to fall to death) | Suicidal (car using bridge ends up in river) |

| 50% Completion | Suicidal (jumping causes animal to fall to death) | Suicidal (car using bridge ends up in river) |

| 75% Completion | Suicidal (jumping causes animal to fall to death) | Suicidal (car using bridge ends up in river) |

| 100% Completion | Marginally beneficial, or maybe not – still great risks in gliding, and sparse benefits | Beneficial (car is able to cross bridge) |

So it seems that the

appearance of gliding cannot be explained using Darwinian ideas. We

have no explanation of how a species would have evolved the first 10%

or the first 20% of gliding functionality, which would have had no

“survival of the fittest” benefit. It's the same type

of problem involved in trying to explain the evolution of flying

without imagining gliding, which gives us problems such as the fact

that there would be no survival benefit if just a wing stump ever

appeared.

Then there's also

the fact that if one imagines gliding animals turning into flying

animals, you have no explanation of how all the changes occurred

needed to change from gliding animals to flying animals. Trying to

explain how Darwinian evolution could have produced “the

development of gliding” plus also “the evolution from gliding to

flying” is not easier than trying to explain how Darwinian

evolution could have produced only the evolution of flying.

For the reasons

giving above, trying to make the evolution of birds seem easy by

suggesting that nature first evolved gliding animals and then evolved

birds from such animals is like reasoning that it's not very hard to

climb to the top of the Met Life skyscraper in midtown Manhattan

using outer wall climbing, because you can first climb the outer

walls of the Chrysler building and then jump to the top of the nearby

Met Life skyscraper. Alternate theories discussed by Dawkins to

account for the origin of flight are not any more credible, and we

can chuckle at his suggestion that perhaps feathers were first

developed to catch insects. Dawkins has no clear story to tell us,

saying that “perhaps birds began flying by leaping off the ground,

while bats began by gliding out of trees” while adding that

alternately “perhaps birds too began by gliding out of trees”

(page 126). Such uncertainty does not amount to a convincing story

of how flight appeared in birds.

In Chapter 8 Dawkins

begins trying to explain how vision could have evolved through random

mutations and natural selection. He uses the “smoke and mirrors”

trick followed by similar reasoners, by focusing on the eye and

acting as if we merely need to explain the appearance of eyes to

explain the appearance of vision. Proceeding in such a way is very

fallacious, because the eye is merely one part of a complicated

system needed to explain vision, what we may call the vision system.

The main elements of the vision system are:

- The eye, which in modern organisms is an intricate arrangement of parts

- Extremely complicated proteins and biochemistry used by the eye to capture light

- The optic nerve connecting the eye to the brain

- Extremely complicated changes in the brain needed for an organism to make use of inputs from the eye.

These parts are so

complicated that even the most primitive vision system providing a

minimal benefit will require an extremely complicated invention

exceedingly unlikely to appear by chance, as unlikely as falling

trees forming into a nice roofed log cabin. You cannot explain such

an invention merely by describing how a primitive eye could appear.

To try to explain

how a primitive eye could appear, Dawkins appeals to a scientific

paper published by Nilsson and Pelger, and Dawkins inaccurately

describes this as a “computer model.” The paper does not actually

describe any computer model or computer simulation. The paper

describes how a circular patch of light-sensitive cells could change

into a curved cupped eye, conveniently assuming that it underwent

exactly the changes that would bring about such a thing (which would

be most unlikely to occur given the thousands of possible ways that

random mutations might change the appearance of such a flat circular

patch). The paper cheats by assuming that such a flat circular patch

of light-sensitive cells would come to exist before it had any

usefulness. The paper also includes absurd statements such as “The

evolution of an eye can thus be compared to the lengthening of a

structure, say a finger, from a modest 8 cm to 8000 km, of a fifth of

the Earth's circumference.” That is wrong because the evolution of

an eye would be the assembly of a very intricate arrangement of

coordinated parts, something vastly more complicated than just a mere

lengthening of an object.

I can describe the

type of smoke-and-mirrors trick involved in Nilsson and Pelger's

paper. It works like this: given some complex functional arrangement

of parts that is incredibly hard to achieve by chance, you try to

make it look easy by ignoring 45% of the arrangement, and also

assuming that another 45% of the arrangement was conveniently there

to begin with; and then you argue that it's easy to make the

arrangement because it's not too hard to make the remaining 10%. So,

for example, someone might argue that it's pretty easy to make a

suspension bridge, by ignoring the whole superstructure (the towers

and the steel cables), and just assuming that the huge complicated

substructure (leading down into the river) just happens to

conveniently exist, and then kind of talking as if making a

suspension bridge is as easy as building a road.

This is very close

to what Nilsson and Pilger have done. They've simply ignored the

requirements of an optic nerve and the incredibly complicated brain

changes needed for vision, and they've assumed that the

light-sensitive cells (so hard to achieve because they require

fantastically improbable and intricate light-capturing proteins) were

just there to begin with. Having either ignored or assumed the prior

existence of 90% of a vision system, they then argue that the

remaining part is easy, so it's easy for animals to get vision. This

is a huge fallacy which Dawkins repeats, because he's so very eager

to believe that vision is an easy hurdle for evolution to jump over.

Ignoring the almost

unfathomable intricacy of a vision system, Dawkins seems to think

that explaining eyes is as easy as explaining how some cells might

simply form into a cup-shaped curve. Similarly, a person might

fallaciously claim that it's real easy to make a camera, because all

you need is a little box shape – or that it's easy to make a moon

rocket, because all you need is a big tube shape.

Here is a

description of the insanely complicated light-capturing biochemistry

going on in the eye, from a biochemistry textbook:

- Light-absorption converts 11-cis retinal to all-trans-retinal, activating rhodopsin.

- Activated rhodopsin catalyzes replacement of GDP by GTP on transducin (T), which then disassociates into Ta-GTP and Tby.

- Ta-GTP activates cGMP phosphodiesterase (PDE) by binding and removing its inhibitory subunit (I).

- Active PDE reduces [cGMP] to below the level needed to keep cation channels open.

- Cation channels close, preventing influx of Na+ and Ca2+; membrane is hyperpolarized. This signal passes to the brain.

- Continued efflux of Ca2+ through the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger reduces cytosolic [Ca2+].

- Reduction of [CA2+] activates guanylyl cyclase (CG) and inhibits PDE; [cGMP] rises toward “dark” level, reopening cation channels and returning Vm to prestimulus level.

- Rhodopsin kinase (RK) phosphorylates “bleached” rhodopsin; low [Ca2+] and recoverin (Recov) stimulate this reaction. Arrestin (Arr) binds phosphorylated carboxyl terminus, reactivating rhodopsin.

- Slowly, arrestin dissociates, rhodopsin is dephosphorylated, and all-trans-retinal is replaced with 11-cis-retinal. Rhodopsin is ready for another phototransduction cycle.

We have no mention

of any of these complexities in Dawkins' book, which show the

absurdity of his claims that it's easy to get an eye. The text above

mentions proteins that are far more structurally complicated than a

primitive eye, such as a rhodopsin protein specified in a gene that uses 1000+ base pairs to specify the protein.

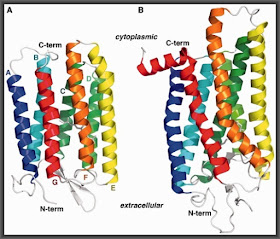

Rhodopsin proteins used in vision

With a vision system

we have the same type of “uselessness of a wing stump” problem in

explaining the origin of flight. Aquatic animals are believed to be

the first that had eyes. But imagine an aquatic animal with only the

poorest type of vision, the type of vision you have if you cover your

eyes with 2-ply toilet paper. With such vision the aquatic animal

couldn't tell if other aquatic animals are far away, but it could

only tell if they are very close (seeing just a very blurry blob

ahead of itself). But a blind aquatic animal could already tell when

another aquatic animal is very close, from its splash (and in a sea

of blind fish, if you're a blind fish you will have other fish

frequently bumping into you). So if a blind aquatic animal in a sea

of blind aquatic animals gets the weakest type of vision, some

extremely blurry vision, it doesn't produce a benefit. Very weak

vision might also allow an aquatic animal to know which way was up in

the water. But a blind aquatic animal could already tell that from

temperature changes in water and pressure changes (the deeper you go,

the colder it is and the greater the pressure). And an aquatic animal

doesn't need to know which way is up in the water.

So the poorest type

of vision would have no survival value for an aquatic animal. If

there were to be some incredibly improbable set of random mutations

allowing the poorest type of vision, that would not be rewarded. For

an aquatic animal, there is no series of gradual changes, each

rewarded, that leads to the advanced functionality of vision. There

is instead a high functionality threshold that must be reached before

any survival reward is obtained, involving a complex, highly

coordinated arrangement of parts needed to get something better than

the weakest type of vision. We cannot explain how such a high

threshold could be reached through random mutations and natural

selection. For the threshold to be reached, too many complex parts

have to be assembled with too much coordination. Far from being an

“easy back route,” this is a high cliff like the front face of

Half Dome in Yosemite.

Natural selection is

merely a dumb filter, something that can filter out bad designs but

cannot explain the appearance of good designs. There is a very

general reason why random mutations plus natural selection (a

survival reward for greater fitness) cannot explain the origin of

complex biological functionality. The reason is that the early

stages of bringing into place such functionality would in general not

yield rewards. Fragmentary implementations yield only very poor

rewards or no rewards at all, and it is usually true that no reward

is produced until a large fraction of an implementation is produced.

So in almost all cases it is not possible to describe a pathway by

which a series of random gradual changes could yield very complex

functionality, with the early parts of the pathway producing a

significant reward. If there is no reward in the early parts of the

implementation pathway, it is gigantically improbable that nature

would walk down that pathway, which would be only one of quadrillions

of possible random paths.

The diagram below

illustrates this point. The part in red represents the initial

stages of a biological innovation, stages that are pre-functional and

therefore not explained by an appeal to natural selection, which can

only come into play once a functional threshold has been reached.

Dawkins tells us

that eyes independently evolved 44 times, and scientists say that

random mutations would have to occur 100 times for a particular

biological innovation to become fixed in the gene pool. This means

our orthodox Darwinist is required to believe that 4400 times blind

chance produced a vision system, which is rather like believing that

4400 full water-tight log cabins have been produced by random falling

trees in forests (although the latter is far more likely). Given the

intricacy of a vision system, vastly greater than a log cabin, we

would not expect a vision system to have arisen by chance mutations

and natural selection even once in the history of our galaxy. So when

Dawkins tells us that an eye can appear on the evolutionary scene “at

the drop of a hat,” your fairy tale alarm should start ringing

very loudly.

Considering

all of its required parts (including very complex brain changes,

fine-tuned proteins, an optic nerve, and intricate eye anatomy), a

vision system is one of the most complex cases of organized

functionality known to man. Adherents of the Darwinian “modern

synthesis” have no way to account for this, for they lack any

theory of organization. Darwinism is a theory of accumulation,

not a theory of organization – the accumulation of random changes

by mutations. As an evolutionary biologist confessed recently,

“Indeed, the MS

[modern synthesis] theory lacks a theory of organization that can

account for the characteristic features of phenotypic evolution, such

as novelty, modularity, homology, homoplasy or the

origin of lineage-defining body plans.” But what do some people do

when they have to explain mountainous levels of organization, and

they lack a biological theory of organization? They try to fake

their way through, by using verbal tricks, carefully selective prose

and omissions to try to make the mountain of organization look like a

mere molehill of organization.

We may compare

Darwinian evolution to a man trying to build elaborate structures,

but who is acting under two handicaps. The first is that he has a

refrigerator-sized steel block chained to his leg. The block (causing

such slowness) symbolizes the fact that Darwinian evolution relies on

favorable random mutations to achieve innovations, but such mutations should be so rare that

waiting for them means the Darwinian evolution of complex macroscopic innovations should work no faster than

a snail's pace. We may also imagine that this man has been commanded to operate under a rule of “do 100 harmful things for every useful

thing you do.” Such a rule symbolizes the fact that for every

random mutation that is helpful, there are very many that are

harmful. How fast should such a man be able to build useful

structures? Never faster than an insanely slow pace. So if the fossil

record shows something like the Cambrian Explosion, in which every

major phylum of animal now existing appeared in a relatively short

time, we must suspect something was going on much more than just

Darwinian evolution by random mutations and natural selection.

Any convincing

naturalistic attempt to explain the origin of vision and the origin

of other complex biological functionality would devote a great deal

of time to explaining the exceptionally fine-tuned and intricate

biochemistry of life, and would also devote a great deal of time to

explaining how it is that so many fine-tuned proteins came to arise

in human biology. For countless proteins there is what is called a

steep fitness landscape. This means that the proteins can only

function well if they have a small number of states very similar to

their existing states. Explaining the origin of such proteins is a

nightmare for thinkers such as Dawkins who maintain that nothing but

blind chance and natural selection brought these proteins into

existence. Calculations repeatedly indicate that it would take

something like ten to the seventieth power tries or search attempts

for nature to find a particular type of protein known to exist; and

there are thousands of such proteins in the human body. The number

of search attempts that nature would have time to accomplish in the

history of the earth is some number trillions of times smaller.

Does Dawkins book

have some chapters trying to explain the origin of fine-tuned

proteins? To the contrary, there isn't even an entry for proteins in

the index of his book, nor is there an entry for chemistry or

biochemistry. We would also expect that any convincing naturalistic

attempt to explain the origin of vision and the origin of other

complex biological functionality would devote a great deal of time to

topics such as coordination and coherence, since the marvel of

biological functionality is largely the wonder of how lots of small

parts can work together in such a coordinated and coherent way. But

we find no entry for “coordination” or “coherence” in

Dawkins' index, which also doesn't have an entry for “complexity.”

Dawkins book fails

completely in its attempts to show “easy back routes” by which

Darwinian evolution could produce great wonders of complexity. He

fails to provide a single example of some impressive piece of

macroscopic biological functionality that has been proven to have

been produced by natural selection and random mutations. No such

example exists. Dawkins also fails to provide a single plausible

story leading us to think that natural selection and random mutations

would have been capable of producing any impressive piece of very

complex macroscopic biological functionality.

In this regard

Dawkins is in good company. The passage on vision biochemistry that I

quoted is from page 459 of the 1119-page biochemistry textbook

Lehninger Principles of Biochemistry. The book gives us a

thousand pages of description of the most intricate machine-like

biochemistry in the human body, but does basically nothing to explain

how this functionality could have originated (apart from a short

pro-forma review of Darwinism tenets, which don't specifically deal

with biochemistry). There is endless discussion of proteins, but

when I look up “proteins, evolution of” in the index of the book,

I am referred to 5 pages that make no substantive clarification as to

how fine-tuned proteins could have naturally evolved. How did we get

all these thousands of fine-tuned proteins, each so fantastically

unlikely to have arisen by chance? Our 1119-page biochemistry

textbook has no real answer. Similarly, the 1041-page textbook

Biochemisty by Lubert Stryer of Stanford University is notable

for making no substantive attempt to explain the origin of any part of the

wonderful biochemical machinery it discusses. The index of the book

lists only 20 pages referring to evolution, and when I look up those

pages I find only passing or incidental references to evolution.

Mentioning Darwin in only one paragraph, with only a passing mention,

the 1041-page book lacks even a substantial exposition of Darwinian

theory, and doesn't even mention natural selection in its index, ignoring the topic of the origin of life and the origin of

proteins. Which is not what we would expect if Darwinian theory were

useful in explaining the origin of life or very complex biochemistry

machinery.

Nor is there any

real origins answer offered by this long recent review of the topic

of protein evolution, which states this near its end (referring to

protein folds):

It is not clear

how natural selection can operate in the origin of folds or active

site architecture. It is equally unclear how either micromutations or

macromutations could repeatedly and reliably lead to large

evolutionary transitions. What remains is a deep, tantalizing,

perhaps immovable mystery.

No comments:

Post a Comment